OpenVenti: Vicente Adum helps to bring hope to Ecuador

“I was born to be a mechanical engineer,” says Adum, who grew up in Ecuador’s largest city, Guayaquil, a seaside metropolis of 3 million people. “My father is a mechanical engineer, so I was always around construction projects, equipment, and factories. That’s what I was meant to do, and that’s what I did!”

He enrolled in Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL), and while studying thermodynamics, he noticed something unique about his textbooks. “In our heat transfer course, the book we had was by Incropera and Dewitt, who were professors at Purdue University,” says Adum. “Our fluid mechanics textbook was by Fox and McDonald, who were also from Purdue. I also saw Professor Rao’s book on mechanical vibrations. I was curious about all these authors from Purdue University.”

Adum received a scholarship in Ecuador, and was asked to provide three choices for where he wanted to attend graduate school – but he only had one choice. “I love thermal sciences, and Purdue was the only place I wanted to go!”

It wasn’t smooth sailing at first. “I wasn’t used to such a demanding academic environment,” remembers Adum. “I came into class with a little 1-inch folder, and soon found out I was going to need a bigger folder!”

“Once I got into the rhythm of it, I had such a great experience,” he continues. “These professors were amazing: Jim Braun, Eckhard Groll, Issam Mudawar. They actually checked everything on my homework and wrote notes explaining what I had done wrong. I had a class with Suresh Garimella, who called me by my name on the first day. We had never even met!”

“I learned a lot at Purdue,” says Adum. “Most of the things I’ve learned, I’ve tried to apply here in Ecuador.”

Adum ended up teaching heat transfer and thermodynamics at his alma mater, ESPOL. He also served as general manager at several construction companies, and started his own company, Metalco, specializing in engineering, procurement, and construction for industrial projects in Ecuador. “We are a one-stop-shop,” says Adum, “we do whatever needs to be done, for any size project.”

Standing together

The OpenVenti project has its roots in an earlier disaster. In April 2016, a massive earthquake struck Ecuador, killing 676 people and injuring more than 16,000. A group of local entrepreneurs collaborated to raise money and bring drinking water to the devastated region. When COVID arrived in the country in 2020, the group were motivated to reconvene and jump into action.

“At first, we all thought COVID was a problem somewhere else in the world,” remembers Adum. “Then we had the first case, right here in Guayaquil. And it hit us hard. There were coffins lining the streets in Guayaquil, because there weren’t enough people to bury the bodies.”

“We felt so helpless,” says Adum. “And we’re all in lockdown. What can we do? We have to do something.”

That same network of entrepreneurs, led by Edgar Landivar and coordinated by Paul Estrella, started to meet over Twitter and Slack to discuss how they could help. They decided to create a simple open-source mechanical ventilator, which was sorely needed in the hospitals of Ecuador. “We are all entrepreneurs, and most of us are engineers,” says Adum. “This is the kind of project that requires technical knowledge, but also a huge amount of logistics. But we all have experience in sourcing parts, manufacturing, and financing. With all of us, we might be able to do it.”

For all their experience, they did have a gap in their knowledge base: no one had ever built a mechanical ventilator. “All we knew was that you need air in your lungs to breathe,” says Adum. “So we enlisted the help of doctors and specialists, who could tell us exactly what was needed for a device like this.”

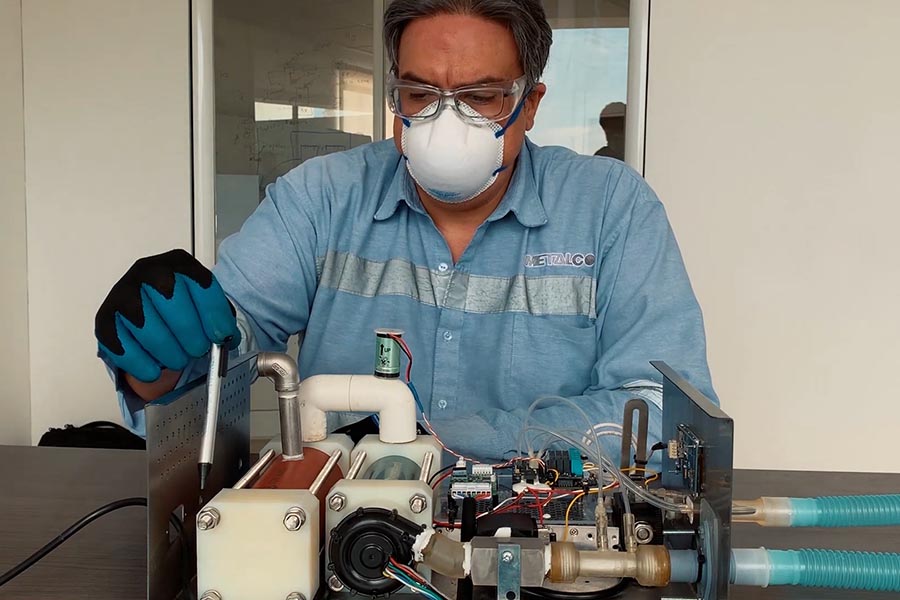

Adum jumped in to help with the mechanical design of the prototype, focusing on its pneumatic systems. The lockdown made collaboration especially challenging. “We had a team of almost 400 professionals, but we couldn’t physically get together,” remembers Adum. “We were doing everything by Zoom and by phone calls, building the pieces for the prototype in our own houses!”

Get it done

“Our philosophy was to get it done,” he says. “Whatever we had to do to get parts and build it, we did it. This was an emergency situation. We were not thinking about making money off this. We were trying to save lives.”

They eventually succeeded. Their creation, OpenVenti, costs about $1,000 to build, which is about twenty times less than what an open-market ventilator would cost. It’s also open-source, so that people anywhere in the world can build it using the plans they have posted online. They built 200 of the devices, which they donated to Ecuadorian hospitals, with the help of GoFundMe donations and corporate gifts.

“When we were delivering these ventilators to hospitals, we didn’t realize the difference they would make,” says Adum. “When we received the first video of a patient breathing by OpenVenti, it was a lot of mixed emotions. It was great to see the equipment was working properly, and we achieved our goal. But it was so hard to see these poor people trying to survive. It moves all of us every time.”

Hope through engineering

While Ecuador’s population is slowly receiving vaccinations, COVID is still a very real danger there. But for Vicente Adum, it has also provided a reason for renewed hope. “Sometimes it’s difficult to do business in such a small country, and for a while, I had lost faith,” he says. “But seeing how we collaborated on this project, I regained a lot of my hope. I saw that it was still possible to do great things. It gave me confidence, and it’s inspired me to expand my business in Ecuador. I’m optimistic that we’re all ready for a recovery.”

Many Purdue alumni have participated in similar projects around the world. Tyler Mantel (BSME ’13) paused work on his own startup company to found The Ventilator Project to manufacture low-cost ventilators for the US and other countries. Matt Schmotzer (BSME ’12, MSE ’17) diverted his efforts as a Product Development Engineer at Ford Motor Company to help mass-produce ventilators at one of their manufacturing plants in Michigan.

“In many ways, my time at Purdue perfectly prepared me for a project like this,” says Adum. “You don’t only learn the science at Purdue, but you learn how to do it. You learn how to analyze and dissect a problem into different pieces, and then put them back together to find a solution. I always keep Purdue in mind!”

Writer: Jared Pike, jaredpike@purdue.edu, 765-496-0374