The New Hammer: refining a Purdue ME tradition

Metalworking has been a key part of the Purdue ME educational experience since the days of the first “boiler makers” of the 1800s. But in the 20th century, as computers became increasingly prominent in engineering, faculty found that many incoming students had no hands-on machining experience whatsoever.

“The machine shop can be an intimidating place,” said John Wheeler, who has served as a machinist at Purdue for nearly two decades. “It’s big, it’s loud, and it can be dangerous without the proper training. For students who have never operated these machines, it can be tough to know where to start.”

Prof. John Starkey saw this disparity in the mid 1990s as he developed ME 263, a sophomore-level design class where most students get their first exposure to the basics of manufacturing. As part of the class, Starkey introduced a component where students visited the machine shop, learned about the machines, and made a small hammer as a memento.

The hammer quickly became a popular rite of passage among students. Many alumni keep their hammers displayed in their homes or workplaces as a prominent reminder of their time at Purdue, repeating the “hammer down” mantra shared by all Boilermakers.

A 21st century icon

There's no doubt that the hammer is an iconic part of Purdue ME culture. But as an educational experience, there was still room for improvement.

“It was what I would call a cookie-cutter operation,” said Wheeler. “It’s a simple piece of hexagonal brass stock. All the students had to do was a little milling, a chamfer on the edge, and drill a hole for the wooden handles, which we bought pre-made. Everything was already set up for them, so they didn’t really learn how to do it themselves. Even the word ‘PURDUE’ was engraved by me on the CNC machine.”

What if there was a way to make the original hammer better?

Fast forward to summer 2021. As COVID wreaked havoc with internships and co-ops, many undergraduate students stayed on campus and elected to conduct research or service projects instead. One project, initiated by managing director of technical services Mike Logan, proposed refining the 25-year-old hammer project to put some polish on the old design, while also introducing a more substantive learning experience for students who had no experience in the machine shop. Three undergraduate students – Xing Fan, John Parker, and Kyle Wang – took on the challenge.

So how do you tackle such a beloved Purdue tradition? They started by mimicking another Boilermaker icon, Purdue Pete. “Pete’s hammer was designed to look like a boilermaker’s tool from a steel mill,” said Wang. “It’s got a rounded face (not hexagonal), with an angled flange at the back. So we took our design cues from that.”

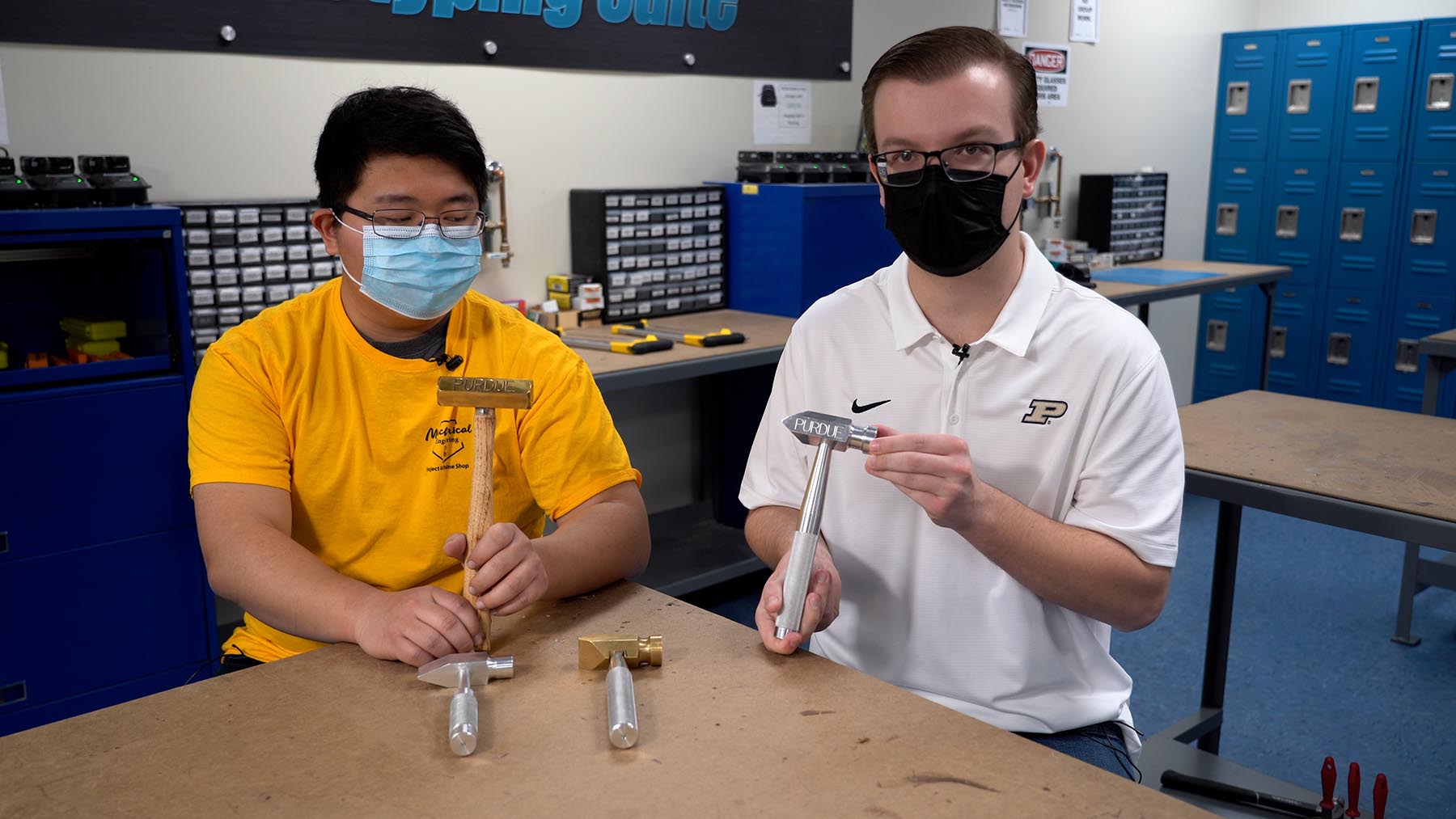

They began with a small prototype, machined out of aluminum, which incorporated the rounded face and flanged back. They added knurling to give the handle some texture, and tapped threads to attach the head to the handle. A second prototype added two inches to the handle, and experimented again with brass stock for the head. But because the two materials gave it uneven weight distribution, they decided to go 100% aluminum.

Throughout the design process, they consulted with machine shop staff to determine how to maximize the educational value, while minimizing the time required. “That’s why we flipped the flange from vertical to horizontal,” said Parker. “This deviates from the Purdue Pete design, but it saves a number of tool changes, which decreases the time necessary to machine the head.”

“They introduced all sorts of teaching moments to the hammer project,” said Wheeler. “Learning something about threads, how to use a tap, running the die, making a knurled handle on the lathe... these are things that students previously had never seen before.”

The final design is a sleek 9 1/2 inches of mirror-finish aluminum, with a satisfying textured handle and a seamless head-to-handle connection. “Everyone I’ve talked to says they like it,” said Parker. “The words I’ve heard people use are ‘sleek’ and ‘aerospace.’ It’s definitely very modern looking. And while the old hammer was very top-heavy, this one is nicely balanced. It’s also much lighter. It’s comfortable when you’re holding it in your hand.”

The other advantage to an all-aluminum build is cost. “The old hammer cost something like $16 to make,” said Wang. “This one only costs $7. So not only does it look better and teach more, it also saves money.”

Scale it up

They presented the finished design to Purdue ME faculty and administration, and received an enthusiastic response. Then the question became: can you repeat this with 400 students a semester?

Enter Darren Wilcoxson, the senior manager of Purdue ME’s maker spaces. With years of experience as a high school educator, he was thrilled with how much more students would learn by making the new hammer. But replacing the old “cookie-cutter” process wouldn’t be easy. “I was a little nervous at first, because it initially took about six hours to make the first new hammer,” he said. “We are giving students one-on-one attention, both with the mill processes and the lathe processes. But part of making a part over and over is that you get better at it, and we saw where processes could be refined. Now it’s closer to three hours for every student.”

They beta-tested the new process in Fall 2021, where about 175 students in ME263 made the new hammer. They added more staff, and stuck to a more rigid schedule to get students the time they needed. Now halfway through the spring semester, they are on track to guide more than 400 students through the new hammer before Spring Break.

“We’re still making changes, up to and including yesterday,” said Wheeler. “Rather than CNC the word ‘PURDUE’ onto the side of the hammer head, we now use a metal stamp with the proper Purdue logo, which students can apply themselves with a hydraulic press.”

“I think that’s a great metaphor to describe what we did,” said Parker. “We just took the old project, and modernized it, and put our stamp on it.”

Feedback from students has been overwhelmingly positive – not just about the cool-looking design, but about their first substantive experience in the machine shop. “They’re leaving the shop with confidence,” said Wilcoxson. “They’ve had a positive experience, and the hammer is a tangible sign of their success. When they need to build prototypes for other classes and projects, they feel like they can do something they couldn’t do before.”

Parker agrees, having served as both a member of the design team, and a part of the project’s target market. “I had almost no experience in the shop when I started,” he said. “I had to lean on Kyle and Xing until I got my feet under me. But if I can make this hammer, it means anyone can.”

The team is also starting to understand their place in history. Says Parker, “It’s really cool that our design is going to be a part of Purdue ME tradition for a long time.”

Writer: Jared Pike, jaredpike@purdue.edu, 765-496-0374