PhD fighter pilot starts drone company

“We’ve created an entirely new aerial platform,” says Adams (MSME ’14, Ph.D. ’16), from his homebase in Idaho. “Most drones tilt and lean in order to move, which makes it difficult for them to perform precise tasks. Adding a cyclorotor allows the vehicle to stay level, while moving quickly and precisely in any direction. This enables the drone to perform precise tasks in dangerous or precarious situations.”

It’s a perfect project for Zach, who has flying in his blood. His father was an airline pilot, and Zach was the kind of kid who would attach a leaf-blower on the back of a skateboard just to see what would happen. He saved up enough money in high school to attain a private pilot’s license, and eventually chose to enroll in the US Air Force Academy to study aeronautical engineering. He then received a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship, which enabled him to attend graduate school... but with a catch. “I was very fortunate to have the chance to work toward a Master’s and a PhD at Purdue, but they put some pretty severe time constraints on it,” he remembers. “It was a very hectic three years!”

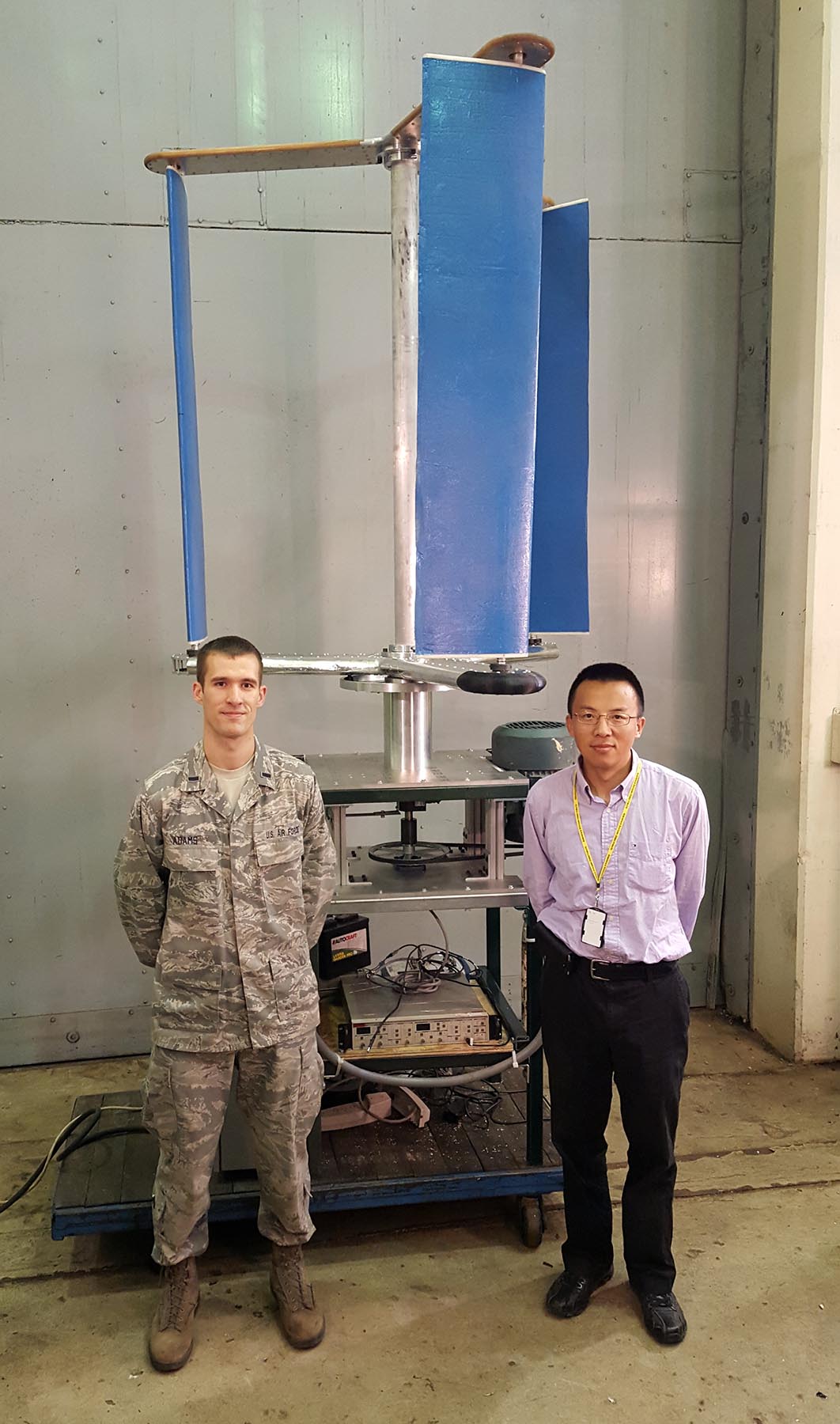

Adams connected with mechanical engineering professor Jun Chen, whose research focuses on fluid dynamics. “I was a little hesitant at first, because of the tight time frame,” says Chen. “But Zach was so well-prepared, and he knew exactly what he wanted to do, which was to work on cyclorotors.”

Cyclorotors are propellers that generate their thrust perpendicular to the motion of the surrounding air. Instead of normal propellers, which spin at the front of the craft, cyclorotors are tall cylinders that spin at the top of the vehicle. They have been known since the 1920s, with their main application maneuvering tugboats in any direction. But Zach had much more ambitious plans for them than just tugboats.

“We had a three-tier approach in designing the perfect cyclorotor,” remembers Zach. “First we built theoretical models, and we spent a lot of time getting the math right. Then we ran a high-fidelity computational fluid dynamics simulation, to visualize the airflows around the turbine blades. And based on that, we built a five-foot diameter wind turbine experiment. We put it in the back of a pickup truck, and drove at high speeds to simulate the motion of the wind. After we got the results, we looked at each other and said, I think we just built the world’s most efficient vertical-axis wind turbine!”

Before long, Zach had to wave goodbye to Purdue, and embrace his other job: flying the F-15E Strike Eagle for the Air Force.

“I love my job,” says Zach. “It’s stressful; there are a lot of demands and responsibilities, and some crazy working hours. There is a ton of preparation, briefing, and teamwork before we ever get airborne. And then it’s a very complex machine to operate. Very rarely do I get a few seconds to just look around and say, ‘Wow, how cool is it to be out here?’ Most of the time my hair is on fire, trying to solve 100 different problems at once! But it’s an unprecedented experience; very few people get to do what I do.”

Start it up

Despite the prestigious job, something still nagged at Zach. “I didn’t want to just give up on what I’d worked on for my Purdue thesis,” he says. “There’s still a lot of value in this, and it needs to continue somehow.”

With support from Purdue Foundry, Zach started a company with some of his Air Force colleagues, to incorporate his cyclorotor into a real-world product. And thus, Pitch Aeronautics was born.

“It turns out that the most dangerous job in the world is not flying Strike Eagles for the Air Force,” Zach says, as part of his well-practiced elevator pitch. “It’s climbing towers and bridges for inspection. These guys are ten times more likely to die than the average construction worker, because they have to physically maneuver themselves into very dangerous positions to accomplish their work. We thought drones would replace some of this work, but today’s drones are just not capable of performing the precise tasks that humans currently do. That’s where Pitch Aeronautics comes in.”

Their drone is called Astria (named after the Greek goddess of precision). It’s a serious piece of kit; the main spar is roughly 9 feet long, with six electric motors providing the upward thrust, capable of carrying a 5-10 pound payload. But the secret sauce sits on top. Zach’s patented cyclorotor, positioned in the middle of the six traditional motors, provides instant thrust vectoring in any direction – enabling the vehicle to make precise movements while remaining level, even in windy conditions.

“At the end of the payload arm, we can put sensors, cameras, or robotic tools that can perform work while the drone remains steady,” he says. “This means that workers don’t have to risk their lives climbing onto bridges, powerlines, wind turbines, skyscrapers, or other precarious locations. Astria allows users to conduct up-close touch-based robotic tasks, safely and reliably.”

Bringing the drone to market has been its own adventure, as they are now currently seeking investors on StartEngine. “I’m an engineer, so the business challenges have been much harder than actually building the machine!” he says. “The Purdue Foundry gave us a lot of helpful entrepreneurship guidance at the beginning. But from there, we’ve figured it out ourselves. We’ve got a great team at Pitch Aeronautics, and we have a compelling business case. But the bottom line to starting a business is, you’ve just got to get your elbows into it.”

Boiler up, up, and away

Zach sees the Purdue influence everywhere in his day-to-day life. “Graduate school actually helped me with the soft skills, like learning how to write well,” he says. “This has helped me translate the ideas I had at Purdue into real-world solutions.”

The influence also goes both ways. “From the first time I met him, I knew right away that Zach was a special person,” says Prof. Jun Chen. “He did so much in his three years here. He gave me my first ever flight lesson at Purdue Airport. He met his wife here [Beth Stanley, a 2016 mass communications graduate]. I wanted my son to emulate the type of man that Zach was, and the two of them had many conversations during those years. Now my son is a freshman at the US Naval Academy, and I’m very proud that Zach played a role in that.”

Zach is also embracing the life of an entrepreneur, which at times can be just as exciting as being a fighter pilot. “I love the flexibility of it,” he says. “You don’t have to restrict yourself to things that already exist. If you’ve got a vision, you can bring it to life. I also like building a team, and I’m really proud of what our team has accomplished in such a short time. More than anything, this shows that research is not just a task in and of itself; it can be a stepping stone to bigger and better things.”

Writer: Jared Pike, jaredpike@purdue.edu, 765-496-0374

Pitch Aeronautics: pitchaero.com