Jimmy Kenyon takes the reins of NASA's Glenn Research Center

The Power of Propulsion

Kenyon grew up in a small rural town in Georgia, working in the peanut fields during the summer. “We lived near a big lake with a dam,” he remembers, “And occasionally I would see jets fly exercises over the lake. That really sparked my interest in aerospace.”

He began attending Georgia Tech for aerospace engineering in 1991, which was unfortunate timing; with the Cold War ending, the market for jobs in defense and aerospace dipped dramatically. “Georgia Tech graduated 100 aerospace engineering majors a year, and that year I think only 4 of them got jobs,” said Kenyon. “My class started with 150 students, and five years later, only 26 of us graduated.”

Seeking any port in the storm, he was fortunate to find a great co-op experience at Delta Airlines in Atlanta, where he became intimately acquainted with jet engines. After graduating, he took advantage of an Air Force program that employed him as a civil servant, while also funding his graduate school. Since the Air Force wanted him to continue to study propulsion, they sent him to the largest academic propulsion lab in the world: Purdue’s Zucrow Labs.

“I studied with Sandy Fleeter, who was world-famous when it came to gas turbines,” said Kenyon. “He was an interesting character, and it was fascinating to pick his brain about unsteady aerodynamics. I think he supervised 26 graduate students at the time, and boy did he work us hard. He used to drive out to Zucrow Labs late at night, just to see whose office lights were on!”

Kenyon said he learned a lot of lessons at Zucrow: “Sandy ended up being a great mentor. He taught me how to prioritize working with multiple stakeholders – industry, government, customers, co-workers. Those are lessons I still carry with me today here at NASA.”

After completing his Master’s degree at Purdue, he continued to work for the Air Force Research Laboratory, picking up a Ph.D. at Carnegie Mellon along the way. In 2006, he was tapped by the Office of the Secretary of Defense to come to Washington and serve as Associate Director of Aerospace Technology, helping to provide guidance and oversight to more than $800 million annually of aerospace research and engineering programs. In 2013 he joined the private sector, helping to develop new propulsion technologies at Pratt & Whitney in Connecticut.

“I’ve been blessed to have a foot in both worlds, government and industry,” said Kenyon. “I love government service; I love making an impact, being dedicated to a mission, and being a part of something bigger than yourself. But I love industry as well. In the end, it’s all about the people. They are our greatest resource. I got to interact with teams of really smart people who made these projects happen, and when you interact with the best and the brightest, you get an amazing opportunity to impact what’s next.”

What’s Next

For Jimmy Kenyon, “what’s next” happened to be NASA. He joined their Advanced Air Vehicles program in 2019. Three years later, he was appointed full-time director of NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, one of the 10 NASA centers across the country,

So what exactly happens at Glenn Research Center? “Our main core competencies are power, propulsion, and communications,” said Kenyon. “Power deals with energy generation, storage, and distribution, and we do that for both aircraft and spacecraft. Someday we want to go to the Moon and Mars, and we’ll need power once we get there! A big part of the technology behind that is being developed here at Glenn.”

Propulsion researchers also thrive at Glenn. “Our specialty is in-space propulsion, such as Hall-effect thrusters or ion thrusters, that help your spacecraft to course-correct and keep it on station,” said Kenyon. “But it’s not just space-based propulsion. We’re developing new vertical takeoff and landing technologies for aircraft. We’re developing hypersonics. We’re developing electrical propulsion. As someone who studied air-breathing propulsion at Zucrow, I’m particularly excited by the advances made here at Glenn when it comes to aircraft.”

Communications is also a broad umbrella, and Glenn tackles it all. “We are developing all kinds of new solutions, whether it’s optical, laser, RF, or other new technologies,” said Kenyon. “It’s vital for satellites sending back data from deep space, or from air traffic controllers talking to aircraft on earth.”

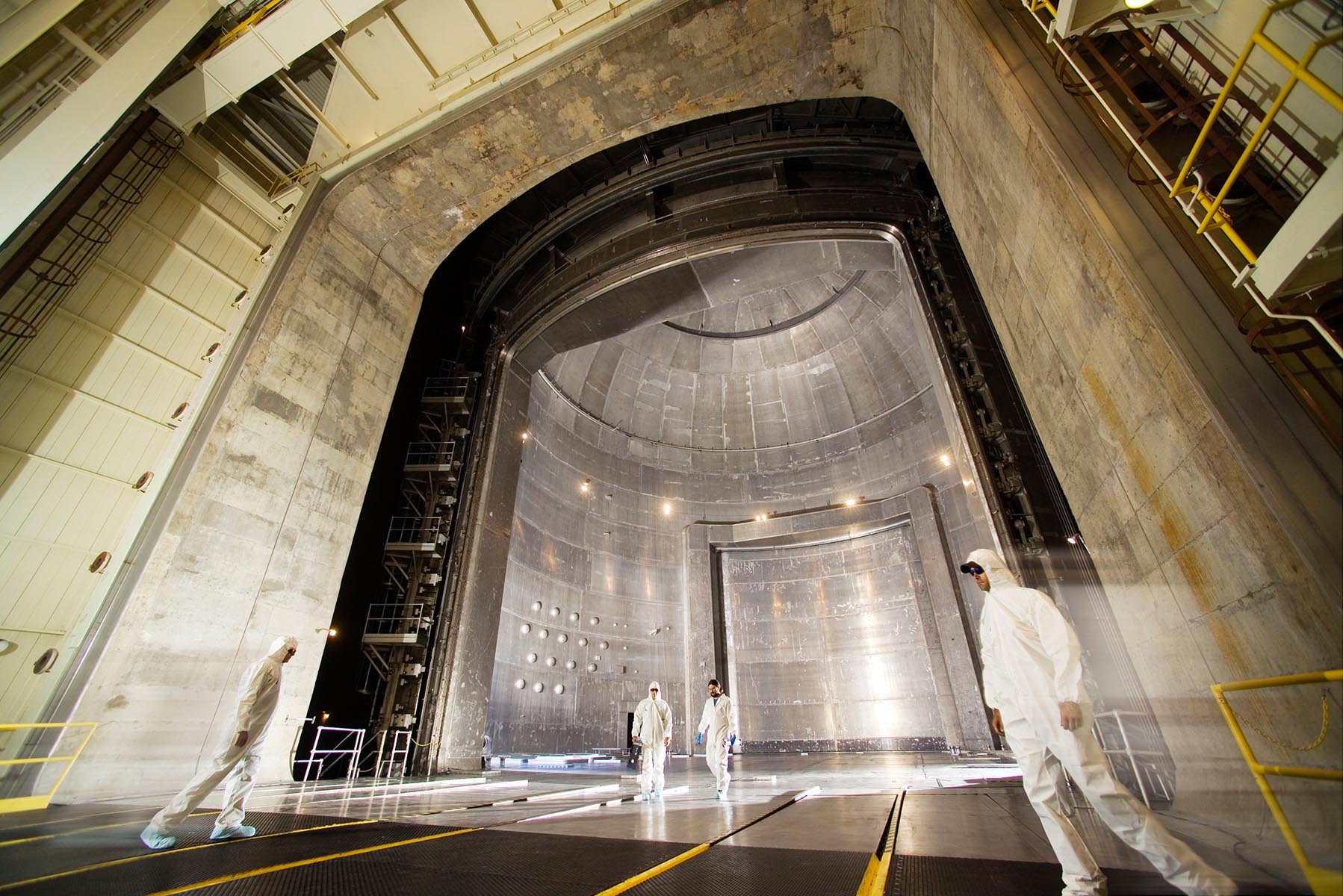

That’s not an exhaustive list of Glenn’s capabilities, of course; they also study extreme-environment materials and structures, physical sciences, biomedical technologies, conceptual design, and much more. Glenn hosts facilities found nowhere else on earth, from zero-gravity drop towers to the world’s largest thermal vacuum chamber. These facilities have played huge roles in nearly all of NASA’s successes over the last year: from the Artemis 1 launch, to the DART asteroid redirect mission, to the upcoming X-59 “quiet boom” supersonic aircraft.

With more than 3,200 employees, how does Jimmy Kenyon handle the pressures of managing a concern as large as Glenn Research Center? “Thankfully, I have a great team of senior leadership around me,” he said. “I like to turn it around and see how much I can learn from these people, rather than me telling them to do this or that. Having smart people who do their jobs well is how Glenn excels at what it does. We want to create an environment where people are excited to come to work, and energized to develop the most advanced aerospace program in the world.”

Boiler Up

While NASA is a huge and complex organization, one observation is easy to make: the place is full of Boilermakers! “From GE to Rolls-Royce, Air Force Research Lab to NASA, I encountered Purdue grads everywhere I went throughout my career,” said Kenyon. “Many opportunities came about because I had that Purdue connection. Purdue engineers have a cultural compatibility, so when you encounter a Purdue grad, you know the job is going to be done well.”

One example of a recent Purdue-Glenn collaboration came from Issam Mudawar, the Betty Ruth and Milton B. Hollander Family Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Purdue, who developed a heat transfer experiment for the International Space Station. Mudawar spent a decade working with Glenn Research Center to develop the Flow Boiling and Condensation Experiment, which launched in August 2021 and became the largest phase-change experiment ever conducted in space.

Kenyon says that his engineering background plays a huge role in his current success. “Someone once told me that getting an engineering degree is learning how to learn. That’s true whether you’re an undergraduate or graduate. Even if you get a Ph.D. like I did, you’ll be the smartest expert on one narrow subject for a time – until someone else comes along and does more research! But when you’re an engineer, you learn how to solve problems. And as you progress through your career, the problems become different – it’s less about solving equations or conducting experiments, and more about leading a team and finding solutions together.”

Writer: Jared Pike, jaredpike@purdue.edu, 765-496-0374