French lithophanes combine art with engineering

French impressionist painters turn "light into layers" using brushstrokes of paint. What if we could do the same thing with 3D printing? A group of Purdue University students traveled to France to unite the worlds of art and additive manufacturing.

“I go to France multiple times a year for manufacturing conferences,” said Michael Sealy, associate professor of mechanical engineering. “I thought this was a great opportunity to combine art and additive manufacturing — enabling students to experience impressionist paintings, and then teaching them how it relates to 3D printing.”

The Study Abroad trip “Light to Layers” brought 30 Purdue Engineering undergraduate students to France in May 2025. After a week in Paris touring museums, the group moved to Rouen and experienced the real-world settings for some of the world’s most well-known impressionist paintings.

In addition to the aesthetic appreciation, they also had an engineering assignment. “Each student had to choose their favorite impressionist painting,” Sealy said. “Some chose the gentle lines of Monet, while others liked the big thick brushstrokes of Van Gogh. Then they had to determine how those brush strokes might impact the 3D printing of their lithophane.”

Lithophanes are an artform invented in France in the 19th century. A flat translucent medium (typically white porcelain) is carved to different thicknesses. When a backlight is applied, the amorphous carved surface transforms into a striking monochrome image. Lithophanes have made a comeback in the 21st century, thanks to the new technologies of additive manufacturing.

“Computer programs have made lithophanes easier than ever to generate,” said Scott Fernander, one of Sealy’s graduate students who accompanied the group to France. “The image gets transformed to black and white, and a computer program translates the dark and light areas to thick and thin layers of 3D-printed plastic.”

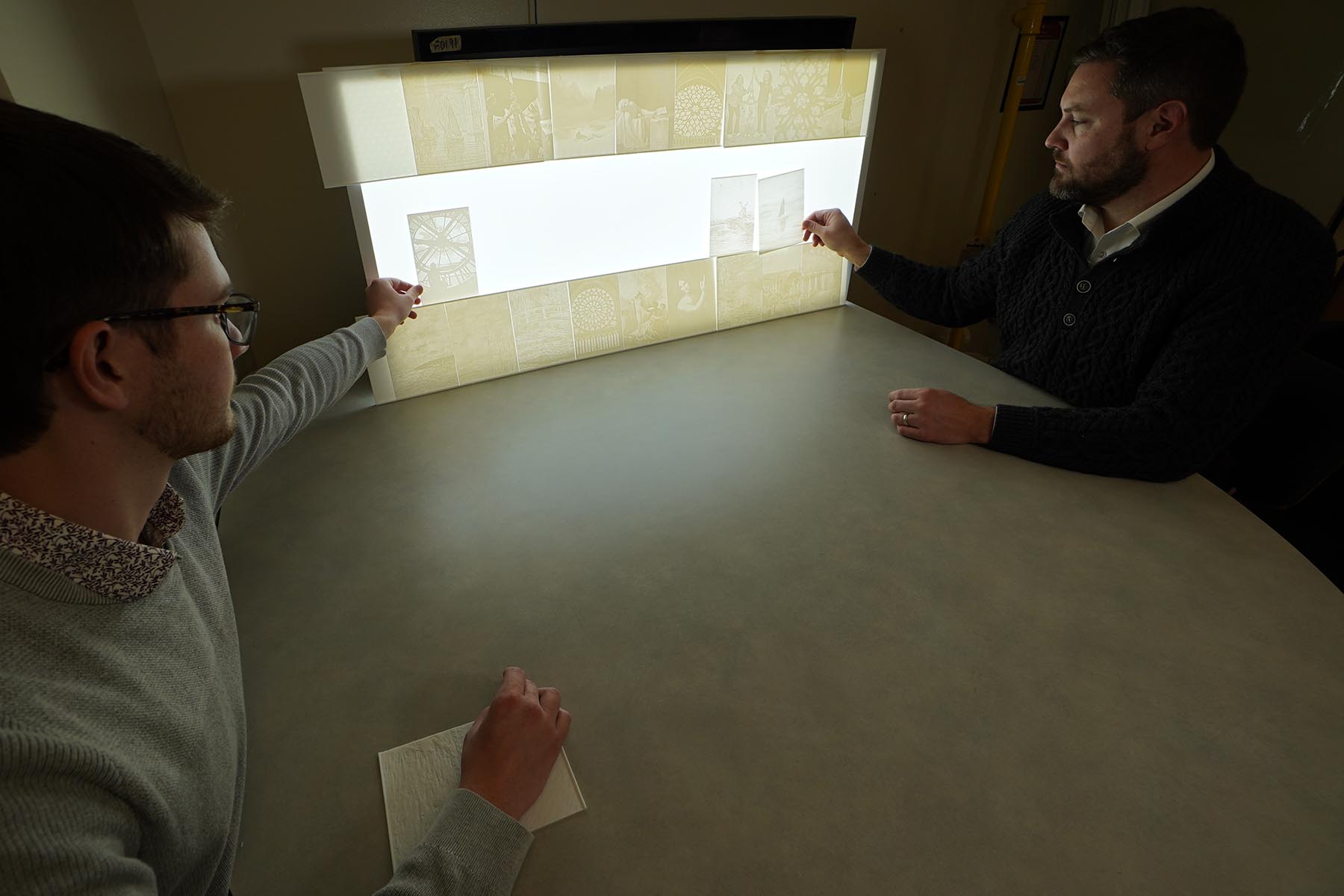

After the students chose their images, they printed their lithophanes at Purdue’s partner university, INSA Rouen Normandie. At first glance, a lithophane appears to be an unimpressive slice of white plastic, about four by six inches. But there’s magic hiding inside.

“Typically when you hold a lithophane in your hand, they don’t appear to have a lot of detail and it’s difficult to tell what the image is,” Fernander said. “But when you put a light behind them, that’s when they really pop.”

The imperceivable thickness differences magically convert into a chiaroscuro of dark and light, transforming the mundane pieces of white plastic into water lilies, sailboats, tulip fields, and even photographs.

“Students wanted to take their photo in front of the Eiffel Tower,” Sealy laughs. “The nice thing about this technology is that simple smartphone photos actually show up really well in a 3D-printed lithophane. The contrast between light and dark in a smartphone photo creates an entirely different creation than one based on the swirling lines of an impressionist painting.”

The trip was so successful, Sealy is planning another “Light to Layers” excursion to France in May 2026.

“This is an amazing opportunity to immerse yourself in French culture,” he said. “The food is amazing, the artwork is world class, and we learn so much from the French communities we visit. Even if you’ve never traveled overseas, I encourage you to try this Study Abroad trip. It’s a great opportunity to merge art and engineering in one of the most beautiful places in the world.”

Source: Michael Sealy, msealy@purdue.edu

Writer: Jared Pike, jaredpike@purdue.edu, 765-496-0374