The Incredible Life of Eric Schwenker

The Adventure Begins

If you called him the King of Evansville, no one would likely disagree.

He experienced all the highs and lows of the 20th century, from right there on 1st Street. He could recite the history of every building downtown, from the oldest factory to the newest hotels and restaurants. He had personal stories from every single thoroughfare, side street, and riverfront sidewalk.

“I’ve got over 90 years of seniority around here,” he joked.

However, Eric Schwenker’s life – his Army adventures, industry success, and influencing an entire generation of engineers – is anything but that of a homebody.

Born in Cincinnati, Eric and his family soon moved to Evansville, which served as a permanent home base for the rest of his life. His father was a heating and refrigeration engineer, and after serving in World War I, continued as a battery commander in the Indiana National Guard. “My dad was a mechanical engineer, so I wanted to be a mechanical engineer,” Eric said. “He also used to take us to field training at Camp Knox – before it was even a fort. They were still using horse-drawn artillery. I was the battery mascot, with a full khaki uniform and everything. So I also wanted to be an artillery officer like him.”

Eric excelled so much in school, that he was placed in the 3rd grade at the age of six. He graduated high school at age 16, two years younger than his classmates. “And I still am,” laughed Eric. “All of them are 101!”

In the fall of 1941, he enrolled at Purdue University. On a Sunday morning in December of his freshman year, he found himself huddled around a radio – like most Americans – to learn from President Roosevelt about the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

In the fall of 1941, he enrolled at Purdue University. On a Sunday morning in December of his freshman year, he found himself huddled around a radio – like most Americans – to learn from President Roosevelt about the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

He finished his first year at Purdue, but saw an uncertain future. Like most cities, Evansville completely re-focused its manufacturing efforts for the war, building LSTs (tank landing ships; the only surviving example floats in Evansville’s harbor today as a museum). Eric worked as a mail clerk in Evansville’s now-bustling riverfront shipyard. Having just turned 18, he knew that an inevitable draft notice would complicate any plans he had for continuing at Purdue, or becoming an engineer. “I had also gotten engaged to a beautiful young lady while working in the shipyards,” he remembered. “We decided that I wouldn’t continue at Purdue; I would just work here until I got drafted.”

Sure enough, in February 1943, he got the “tap on the shoulder.” He was put on a bus to Fort Sill in Oklahoma, and commenced his life as a soldier.

He had dreams of becoming an artillery officer like his father, but his training didn’t exactly go as expected. “I was pretty tall, so they put me in the pack artillery,” he remembered. “These were the big guys who took cannons apart to transport them – except they were transported by mules, which we had to walk alongside for miles! At least my father was able to ride a horse!”

Then, Eric was given a choice: ship out with these mules to hike up and down the jungle mountains of Papua New Guinea, or join the Army Corps of Engineers. “I asked them if those guys ride in trucks,” said Eric. “When they said ‘yes,’ I said ‘yes!’”

So he abandoned his dreams of becoming an artillery officer, and trained as an engineer. He attended Officer Candidate School, and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in June 1944. He had yet to travel overseas, but the time spent stateside had given him the opportunity to marry his sweetheart, Jayne, and have his first baby daughter.

He did eventually ship out to France in March 1945, in an engineer combat battalion. “I only saw six weeks of combat before V-E Day,” he said. “Afterwards, we were all transferred to Frankfurt, Germany to support the headquarters for the Allied Forces, and help re-construct the bombed-out roads and bridges of Germany. I was almost sent to Manila to support the invasion of Japan, but they surrendered in August, and the war was over.”

After returning to the States, Eric left active duty in April 1946. “I had already decided that I wanted to return to Purdue to finish my degree,” Eric said. “My Army certificates probably weren’t going to impress many people once I returned to civilian life, but I knew what a degree from Purdue was going to do for me.”

With his Army experience, Purdue determined that Eric only needed a semester of summer school and a full senior year to finish his degree. And Eric made the most of that time. “Because I already had a lot of drafting experience, I actually taught drafting to industrial engineers in the afternoons, after taking my own classes in the mornings,” he remembered. “I also taught fencing in the Fieldhouse, which I really enjoyed.”

Academically, Eric was drawn to HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning), just like his father. His near-pristine senior notebook from 1946 contains pages of notes and charts about temperature gradients, air distribution, pipe friction, radiators and convectors, and more. “Bill Miller was the professor who taught those classes,” said Eric, “and he also wrote the Professional Engineers’ exam on the subject, so I was well prepared for industry.”

Just like today, Purdue University in 1947 attracted numerous industry recruiters who wanted to hire Boilermaker engineers. Eric met with a representative from International Harvester, who had converted their operations to building P-47 aircraft for the war. Now postwar, they were converting their factories back to traditional industry, building refrigerators and ice makers. And they needed refrigeration engineers... in Evansville, of all places. So in 1947, Eric brought his family back to their hometown, this time to stay.

Evansville became known as the “refrigerator capital of the world,” producing more than 10,000 units per day to supply the booming postwar economy. After Whirlpool took over the business, Eric worked for Whirlpool designing air conditioners and dehumidifiers. He served in sales and design roles for several other companies, and then chose to retire in 1988.

But that was only half of his adventure.

Soldier On

After graduating from Purdue, Eric had stayed in the Army Reserve. He served as the administrative officer for an engineer battalion in Evansville, but found the experience lacking. “I enjoy soldiering,” said Eric, with possibly the understatement of the year. “I saw firsthand my dad’s positive experience in the Indiana National Guard. It was great to have that camaraderie, without getting shot at! So I decided to transfer from the Reserves to the Guard, and join an infantry regiment. I was a platoon leader as a First Lieutenant.”

Eric’s timing was prescient as always. A month after leaving the Reserves in April 1950, the “small skirmish known as the Korean War” began, as Eric put it. Ironically, while all of his former buddies from the Reserves got called up, Eric’s regiment from the 38th Infantry of the Indiana National Guard never went overseas. “They sent six Guard divisions into combat,” he remembered, “and we were going to be the seventh, just before the war ended.”

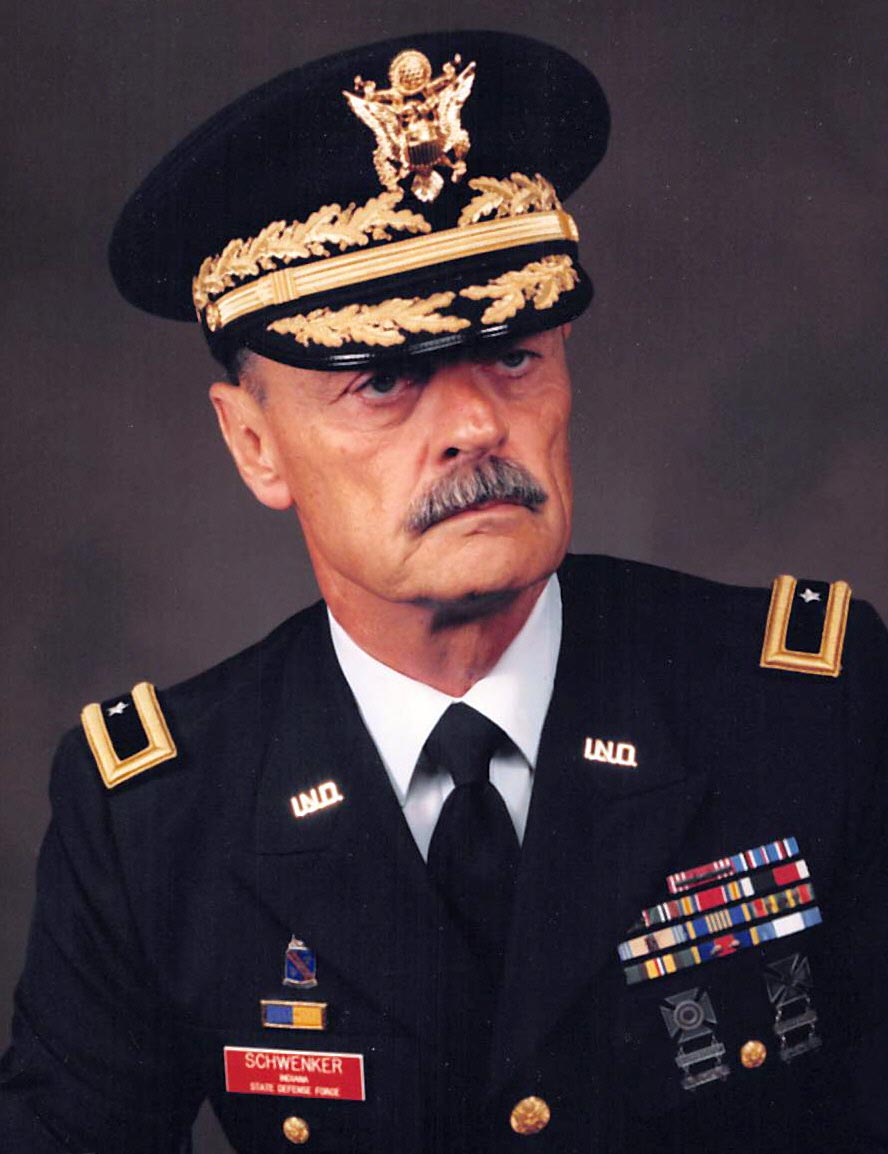

He stayed with the Guard until 1968, achieving the rank of Colonel after 25 years of service. Twenty years later, approaching his retirement in industry, he still occasionally felt the pull of “soldiering.” “They told me I could have a job as long as I wanted,” he said. “I was appointed Chief of Staff to the Indiana National Guard, Commanding General of the Indiana Guard Reserve and promoted to Major General in 1989. I did that for four years, until I turned 70, when I decided to step aside.”

He stayed with the Guard until 1968, achieving the rank of Colonel after 25 years of service. Twenty years later, approaching his retirement in industry, he still occasionally felt the pull of “soldiering.” “They told me I could have a job as long as I wanted,” he said. “I was appointed Chief of Staff to the Indiana National Guard, Commanding General of the Indiana Guard Reserve and promoted to Major General in 1989. I did that for four years, until I turned 70, when I decided to step aside.”

He retired from military service in 1993, but of course, old soldiers never die. Eric continued teaching military classes at Camp Atterbury in nearby Edinburgh, Indiana. His peers described him as “a soldier's soldier.” In 1993, Eric was awarded the prestigious Sagamore of the Wabash for his honorable service in the military.

Dedication

Eric holds another distinction, in regards to the professional organization ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers). Today ASHRAE has more than 57,000 members in 132 countries. But among all members past and present, Eric was the first and only person to celebrate 75 continuous years of membership.

“When I was a senior, Purdue started a student chapter of what was then called ASRE, American Society of Refrigerating Engineers,” remembered Eric. “I said, hey, that’s me! So I joined in March 1947, while I was still in school. When I got back to Evansville, I helped to found their local chapter, which is still going strong. Evansville was full of product design engineers; during the war, they had more manufacturing per capita than any other city, and after the war all those engineers were working on refrigerators.”

Eric sat on numerous technical committees during his time at ASHRAE, and participated on the national level for decades. “I’ve always considered it crucial for engineers to participate in professional societies,” said Eric. “You need to keep up on current information in your field, whatever it is. And don’t just join: ask questions, actively learn, and share your opinions. Doing that face-to-face, you learn so much more than just looking at a screen by yourself.”

And that’s the end of the story, right? Not by a long shot.

“I officially retired in 1988... 34 years ago,” said Eric. “But I always wanted to remain useful. So I started volunteering as a handyman at my daughter’s school.” Eric’s daughter Susie was one of the first teachers at the Signature School in downtown Evansville in 1992, as a half-day accelerated program for high school students. By 2002, it had become Indiana’s first charter high school, and by many accounts, one of the top ten high schools in the country.

And Major General Eric Schwenker changed their light bulbs. For free.

“It started when they were just moving in the building,” he remembered. “They had some storage racks that needed to be assembled, and they asked if I could help, and I said sure. And I just stayed on as a knock-down drag-out maintenance man. I volunteered to do everything, except plumbing and electrical wiring – I know better than to mess with that stuff!”

He relied on that experience when the school had to change 1,000 of their fluorescent light fixtures. “My experience as a product designer really came in handy, because the ballasts of those light fixtures were not always easily accessible,” he said. “I could put myself in the shoes of the designer, and determine where the ballast was, and how best to get to it.”

Keep motoring

Finally, let’s talk about that motorcycle.

“I used a motorcycle when I worked at the shipyard,” Eric remembered. “There were two or three miles of riverfront to cover, so I rode a little single-cylinder job with a centrifugal clutch, to zoom around and get things done. That was in 1942. I never bought a motorcycle of my own until I turned 82!”

He started with a 450-cc Honda, which he enjoyed taking around town. He then upgraded to a 750-cc bike, which took him all over the state of Indiana. “I rode to Indianapolis for military functions,” said Eric. “I visited my daughter in Michigan, which is 400 miles away. I rode in the rain, the snow, the wind... it didn’t matter. The freedom and control you have on a motorcycle – it’s as close to riding a horse as you can get without being on a horse!”

As he got into his 90s, he felt the need to downsize. “I had trouble pushing that big heavy machine around when the engine was off,” he said. “So I stepped down to a 250-cc Honda, which gets me everywhere I need to go in Evansville. And it handles a lot better in the rain!”

When Eric’s five daughters travelled to Purdue in September 2022 to receive his Outstanding Mechanical Engineer award in person, you could almost hear one of his famous quips: “I had five daughters, no sons. All my sons came second-hand!”

Here’s another one about how his family tested his Big Ten allegiances: “Four of my daughters went to Indiana University, and the fifth went to Michigan State! I can't tell you how mad I was having to write those checks! Thankfully one of my grandsons went to Purdue to carry on the tradition!”

In all of his adventures – from the Army Corps of Engineers, to Whirlpool, to riding his motorcycle at age 99 – Eric said that his Purdue education never left him. “Technology is always advancing, but the basics remain the same,” he said. “When you learn about heat transfer, those principles stay the same, no matter what you’re working with. Everything I learned from old Bill Miller stuck with me, and as a product design engineer, I fell back on that knowledge all the time. So what I learned at Purdue, I put into practice for more than 50 years.”

Writer: Jared Pike, jaredpike@purdue.edu, 765-496-0374

A note from the author: before coming to Purdue, I worked at a retirement community for 14 years. I interviewed hundreds of members of the Greatest Generation, each with their own incredible story. Even with all that experience, I have never met a more together 99-year-old than Eric Schwenker. This guy still rode his motorcycle everywhere, even during the winter. He volunteered as a handyman. He kept up with emails. He did 100 push-ups a day. He even still fit in his senior corduroys from 1947!

After our interview in March 2022, he took me out to lunch, and told me that he was planning to attend Purdue’s Homecoming that October. He wanted to ride his motorcycle from Evansville to West Lafayette (a 4-hour drive) so he could celebrate his 75th class reunion. He even asked to go cruising with President Mitch Daniels!

That’s why his unexpected passing, just two months later, really hit us hard. While he didn’t get the chance for that final motorcycle ride, he has been honored posthumously by Purdue as an Outstanding Mechanical Engineer, an award his family accepted on his behalf. It also gives us a chance to share his story with the Purdue community, so they can appreciate his incredible journey.