What Our Students Liked and Didn’t Like about Remote Learning: A Case for Incorporating the Student Voice in Virtual Instruction

Once a bustling, residential campus, Purdue University, like so many other institutions, continued remote learning through the summer in preparation for a “new normal” in the fall. Since March 2020, more than 5,000 courses have been taught remotely with instructors having had less than two weeks to make the initial transition.

On a larger scale, The Chronicle of Higher Education began highlighting survey results for the “Online 2.0: Managing a Large-Scale Move to Online Learning” report, providing insights from faculty and administrators. In recent articles from June 2020, “Did the Scramble to Remote Learning Work? Here’s what Higher Ed Thinks” and “In Their Own Words: Here’s What Professors, Chairs, and Deans Learned From Remote Courses This Spring,” the reader sees what it was like for educators to experience the abrupt shift to online learning, but there is something missing – the student perspective.

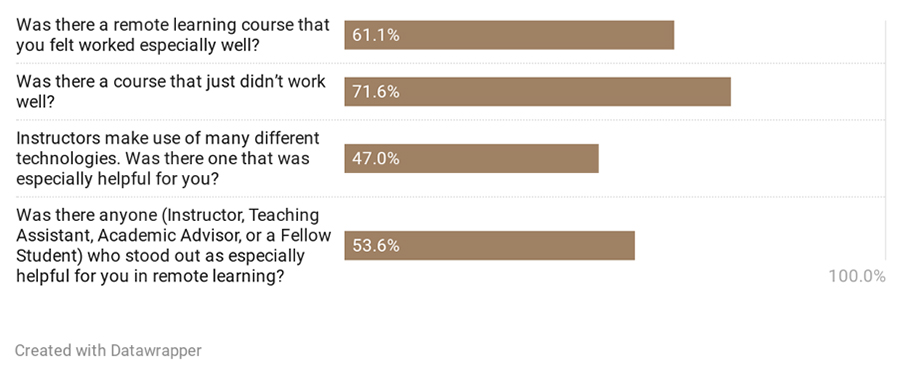

At the end of the Spring 2020 semester, students in Purdue’s College of Engineering were surveyed about their experiences in a virtual environment. In order to uncover the student voice, 544 undergraduate responses were included in the analysis of open-ended questions, both positive and negative, about the shift to remote learning. Students responded to questions about whether they had a class that went especially well, whether they had at least one class that did not work, what about the class worked or did not work, and what technologies were effectively utilized and how. Students also had the opportunity to identify instructors who were effective in the online environment. Figure 1 shows the percentage of “Yes” responses to each question.

More than 60% of students felt there was a course that worked especially well, while just over 70% had a course that did not work well. More than half of students acknowledged that there was a specific person who stood out as being helpful during the transition. Even though students did have negative experiences, their feedback is a vital part of improving remote learning moving forward.

In general, student sentiment was positive, albeit with some disappointment. A student acknowledged that in a tight window “they [the instructional team] put in extra effort to make sure the transition to online as painless and normal as possible.” Another student was grateful for “the care and consideration to students who are trying to adapt to a new situation.”

Three themes emerged from the student voices: 1) personal connection is critical; 2) continuity, communication, and timeliness; 3) effective use of technology. Before the transition to remote learning, students had access to campus resources, organization, and structure (i.e. class schedule, in-person interaction, peer support), but those seemingly vanished once courses went fully online. The analysis of student responses showed that those needs were addressed most effectively through a combination of the three themes.

Personal Connection Is Critical

One theme that emerged was the importance of personal connection. They had more positive feedback for courses in which the instructor communicated often and expressed empathy for the situation. One student said in reference to an aerospace engineering professor, “she also would check in on us. Feeling important to my professor made me want to work harder.” It is easy to think that the content and expertise is the most important aspect of a successful course; however, students need more. Another student wrote, “the professor actively communicated with the class and was considerate of the fact that we would not be able to focus as well with the situation change and added stress.”

The students also appreciated courses in which they could continue peer-to-peer interactions, both academic and informal. In one entry-level engineering course, a student wrote that it was the “only class that continued to have virtual meetings which helped me stay focused and motivated.” Students can continue to thrive in remote environments where personal connections are fostered without having to interact face-to-face. One student summed up their experience in a course where the “…professor held live lectures and called on students to make the class interactive. There was a family feel to the course, whereas others just seemed dry and isolated.” This theme is central to the effectiveness of the next two components.

Continuity, Communication, and Timeliness

One student described their Machine Design course with an instructor who sent weekly to-do lists along with organized course materials, including recorded lectures, and partially complete notes that the students would fill in themselves. The student expressed gratitude for the instructor’s empathy during the transition, which facilitated learning and alleviated stress. In this situation, the organization created by the instructor provided motivation students typically get from peers and regular structure. The following are additional excerpts in which students described exemplar courses and instructors:

“The professor transitioned to online classes in the week before spring break in anticipation of what was to come. The professor also made a new syllabus with clear changes outlined. The class used WebEx for lectures, discussions, and presentations and Discord for small group discussions. Most of all, I liked that we had a Slack community for asking questions or just making conversation. That was really helpful.”

“The professor increased flexibility but still gave weekly updates that kept students from falling behind. The online lectures became smaller modules that were well organized and followed a consistent format. The online exams were created in a way that stayed close to past in-person exams as best as possible.”

Students also described courses as remaining the same or emulating pre-online conditions in contrast to the positive view of pedagogical changes:

“[In an electrical engineering course], the lecturer genuinely put in a lot of effort to deliver the material in a way that we could still learn it. The lectures weren’t watered down. He didn’t just post slides. I felt like it was as close as possible to being in class.”

On the other hand, students felt that some courses did not translate well to a remote format. In some cases, the instructor drastically changed the content or structure of the course, eliminating assignments and/or assessments, that had a negative impact on the students’ experiences. Attempts were not made to mimic the earlier part of the semester so students could maintain a sense of normalcy:

“The professor did not utilize effective virtual teaching methods like WebEx or posting videos. He only used some power point slides and short emails to communicate with the class.”

Not surprisingly, a majority of labs and projects, including senior design courses, left students unable to complete the work or required significant adjustments to the project scope. In some cases, however, departments and instructors were able to ship necessary materials directly to the students. Due to the technical nature of engineering courses, some were also able to utilize simulators and virtual labs. In courses that required project-based group work, students expressed mixed sentiments. Some saw a decrease in group coordination, while others effectively utilized a variety of communication platforms to stay in touch with their teams. The following are instances where the course was not conducive for effective team work:

“Remote learning really doesn’t foster teamwork or group studying and partnered learning. I work especially well with others, and find most motivation through helping others and getting help from others. Isolation took all of that away.”

“In person discussion with lab partners/project groups/ recitation groups was an important part of several of my classes. Not being able to interact with them in person made learning and completing previously group assignments difficult.”

Effective Use of Technology

In contrast, the majority of instructors used a combination of technologies to facilitate relationship building. While lectures may have been given asynchronously through videos posted to the Learning Management System or YouTube, instructors incorporated synchronous office hours and hosted discussions on various platforms:

“[Piazza, discussion platform] provided a method for asking questions about concepts/homework/projects where my questions could be answered by students, TAs, or professors with a quick response time. This is something I wish all classes would keep even during in-person instruction.”

“Human interaction is important, especially when explaining things. WebEx allowed office hours to continue and Discord created a relaxed stop by environment. The main benefit was the simulation of on-campus life and interaction.”

“It was intuitive and easy to use, and instructors regularly monitored it for new questions. Students could also see and learn from others’ questions in addition to their own.”

“Slack was nice to maintain a sense of community and to encourage class discussions, asking questions of the professor and TA, etc.”

“If you engage more, you learn more. Having the freedom to ask questions to the professor, to peers and do it anonymously, removes the barrier of being insecure about your questions. That means more people who wouldn’t normally participate will be much more encouraged to participate. It becomes cool and fun to participate, especially when the professor also engages with the community discussion to make comments and answer questions. It lets us get to know the professor better and breaks down the wall between student and professor.”

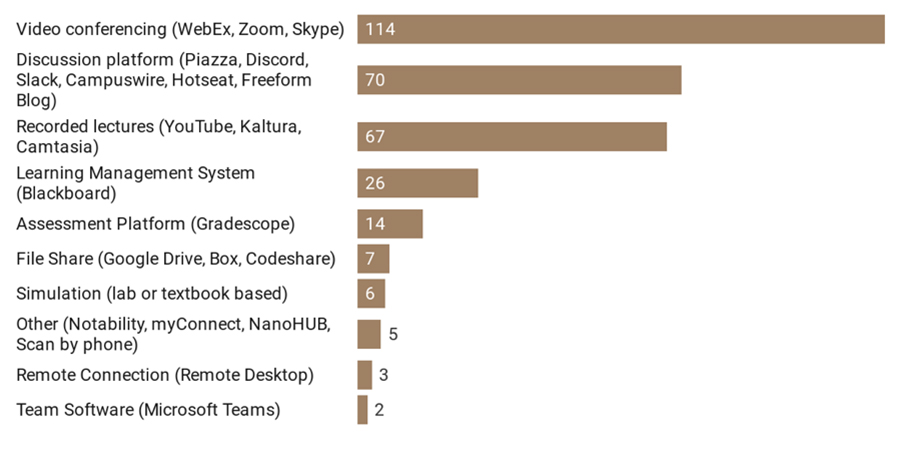

Students overwhelmingly cited synchronous and hybrid delivery, like video conference and discussion platforms, as being helpful during their courses (Figure 2). In most cases, technology was the mechanism for building relationships.

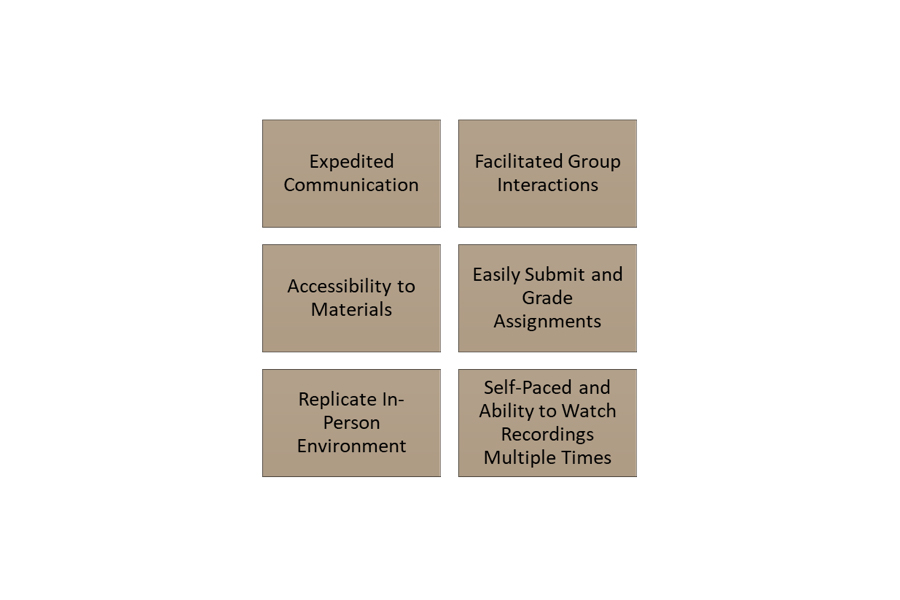

The reasons why students felt technology was effective are illustrated in Figure 3.

While technology played an important and positive role in remote learning, there were still some constraints, including internet quality that served as a barrier for some students. Furthermore, instructors who did not incorporate these measures into their courses, posted low-quality or lengthy videos, or left students with unclear expectations were not viewed favorably; we can still learn from those situations. In all cases, the instructor remained paramount to the success of these new course structures.

Bringing it All Together

For Purdue’s College of Engineering, the findings will be used to inform course development in the coming semester. Some recommendations include the continued use of technology to build rapport between the instructional team and students, including peer relationship building. Frequent and clear communication about course expectations along with streamlined methods for assessment and assignment/test submission are also recommended. One student described specific steps instructors may utilize in their own classes, especially those in technical fields:

“[The professor for my aeromechanics] class was extremely helpful. He quickly restructured the course to be extremely efficient online. For [the lecture section], he moved all lectures to very clear videos that he would often post days ahead of time. He also moved all homework assignments online. He used to hold weekly homework help sessions as a form of office hours. He adapted these to online homework hint documents that were very helpful. His exams were very fair and were offered for large time windows allowing for flexible scheduling. For [the lab section], he found a way to make the lab experiments still meaningful online. We would conduct experiments using a virtual simulation software. This was not as good as in-person labs but it was the best that he could do given the situation, and it kept the labs as meaningful experiences. He also set up a discussion forum for the lab which was brand new -- it did not replace any previous help resources such as office hours, [rather] it was solely an addition. He always communicated changes in course procedures very clearly and quickly and responded to emails almost immediately. He was by far the best professor I had for handling this transition.”

While some of the findings align with the instructor and administrator perspective regarding the abrupt transition to remote learning, moving forward, students may expect more from the online experience. Even as plans continue to evolve, we have had some time to reflect, incorporate feedback, and prepare for the “new normal” that is likely to be a hybrid of remote learning and in-person instruction. It is important to acknowledge the students’ perspective and incorporate their voice as everyone adapts, recognizing all of the elements that contribute to education – not just the content delivery.

Nichole M. Ramirez, Ph.D.

Assistant Director, Vertically Integrated Projects

College of Engineering, Purdue University