Inside Purdue Engineering

Inside Purdue Engineering: Purdue NSBE

The roots of the National Society of Black Engineers are in West Lafayette at Purdue University, dating back to 1971.

February 24, 2023

Inside Purdue Engineering: Co-op program

Purdue's Co-op program, run by the Office of Professional Practice (OPP) housed in the College of Engineering, started in 1954 with the first formal Co-op in mechanical engineering.

January 6, 2023

Inside Purdue Engineering: Industrial Roundtable

The Industrial Roundtable career fair fulfilled a need for Purdue Engineering students when it started in 1980: Help get jobs. It's only grown since, now serving more than 10,000 students and welcoming more than 450 companies each year.

September 9, 2022

Inside Purdue Engineering: Engineering Academic Boot Camp

Since its inception in 2005, the Engineering Academic Boot Camp run by the Minority Engineering Program has had nearly 400 participants.

August 19, 2022

Inside Purdue Engineering: Paper airplanes at commencement

Since at least 1966, graduating seniors in aeronautical and astronautical engineering have been designing, constructing and flying paper airplanes toward the stage at commencement.

May 6, 2022

Inside Purdue Engineering: Beautify Grissom

A competition for IE students asks them to answer the prompt "What does industrial engineering mean to you?" in the form of a painting. Though a cash prize is awarded, the ultimate prize serves to spice up Grissom Hall, as winners of the competition have their canvases displayed within the building.

March 1, 2022

Inside Purdue Engineering: ME Hammer

For more than 25 years, ME students have learned how to use the machine shop by making their own small hammer. Now, students have introduced a new design to bring the hammer into the 21st century.

February 8, 2022

Inside Purdue Engineering: Purdue Space Day

The first in a new series highlighting unique Purdue Engineering traditions. Since 1996, Purdue Space Day has hosted more than 17,000 kids for space-themed STEM activities.

January 18, 2022

Office Hours

Office Hours: A Conversation with ENE's Kerrie Douglas

Kerrie Douglas, a professor in engineering education, chatted with ChE undergraduate Kathryn Bingenheimer in the College of Engineering's video series, "Office Hours."

December 6, 2023

Office Hours: A Conversation with IE/AAE's Barrett Caldwell

Barrett Caldwell, a professor in industrial engineering and aeronautical and astronautical engineering, chatted with ME undergraduate Pranav Parigi in the College of Engineering's video series, "Office Hours."

November 1, 2023

Office Hours: A Conversation with MSE head Dave Bahr

Dave Bahr, head of the School of Materials Engineering, chatted with AAE undergraduate Nachi Yellapragada in the College of Engineering's video series, "Office Hours."

October 5, 2023

Office Hours: A Conversation with BME/IE's Martinez

Ramses Martinez, who has joint appointments in industrial engineering and biomedical engineering, chats with ChE undergraduate Yasar Dambo in the College of Engineering's video series, "Office Hours."

April 28, 2023

Office Hours: A Conversation with ABE's Chaterji

Somali Chaterji, a professor of agricultural and biological engineering, chats with ChE undergraduate Mamie Johnson in the College of Engineering's video series, "Office Hours."

March 31, 2023

Office Hours: A Conversation with ECE's Kulkarni

Milind Kulkarni, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, chats with ECE undergraduate Sam Dlott in the College of Engineering's video series, "Office Hours."

February 28, 2023

Office Hours: A Conversation with ME's Malshe

Ajay Malshe, a professor of mechanical engineering, chats with ME graduate student Mikael Borge in the College of Engineering's new series, "Office Hours."

January 31, 2023

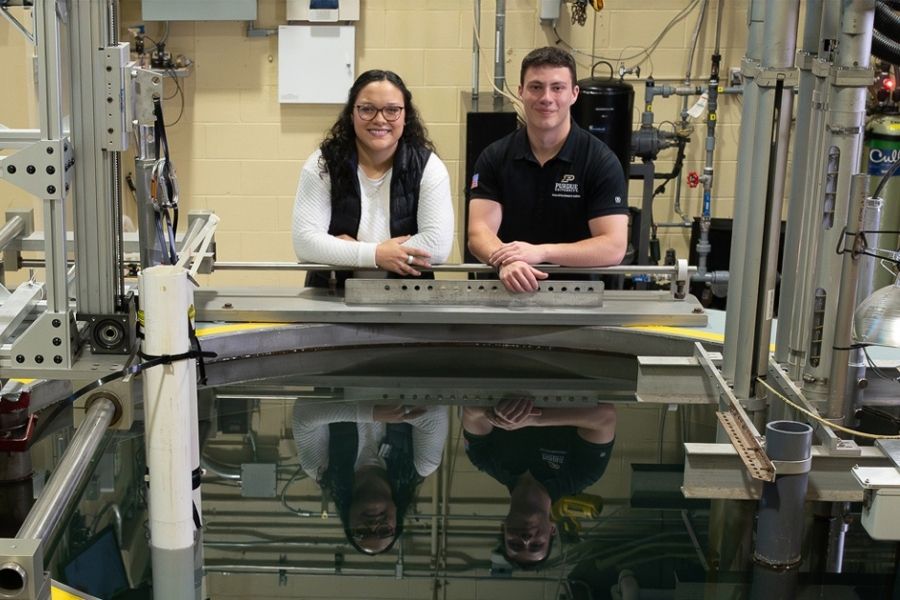

Office Hours: A Conversation with CE's Lu

Luna Lu, a professor of civil engineering, chats with chemical engineering student Rithika Athreya in the College of Engineering's new series, "Office Hours."

December 21, 2022

Office Hours: A Conversation with AAE's DeLaurentis

Daniel DeLaurentis, a professor in the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics, chats with AAE graduate student Nick Gunady in the College of Engineering's new series, "Office Hours."

November 30, 2022