Inspired by the human body, engineer designs chips that could make wearable AI more energy-efficient

Is it possible to use artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT without internet access?

Not yet, but if it were possible, it wouldn’t just expand what we could do with those tools — it also might save lives. For example, someone with a heart condition could wear an electrocardiogram that uses AI to more accurately detect irregularities in the heart, even with a bad internet connection.

Shreyas Sen, an Elmore Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Purdue University, is taking lessons from the human body’s nervous system to design chips that might get AI to work offline for a network of wearable devices without needing to frequently charge them.

Currently, AI’s large power consumption is a major reason why it is only accessible using the internet. AI algorithms are constrained to data centers — massive facilities with servers that make up the internet. Devices such as your smartphone or smartwatch access AI algorithms from data centers over the cloud.

The tech industry is working toward creating “edge” technology, which is a chip that would run AI algorithms directly inside of smartphones or other devices instead of having to access these algorithms via the cloud.

But doing something as complex as learning the whole internet, like ChatGPT does, isn’t possible for a chip right now because it requires too much energy. Sen is custom-designing chips for wearable devices that would allow them to work with edge devices to handle more complex problems with AI using less power, similarly to how a human’s nerves and brain work together.

“If we want to significantly increase the battery life or functionality of a wearable AI device, then we need new mathematical or physical concepts implemented into custom circuit designs. These are not components we can just buy off the market,” Sen said.

How the human body could inform chip design

Custom-designed chips that incorporate the latest advances in mathematical and physical concepts are Purdue’s specialty.

Each year, researchers from all over the world present integrated circuit designs that have the greatest potential to outperform the tech industry’s state-of-the-art chips at the IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC). Purdue is emerging as one of the top universities whose chip designs are selected for presentation at this conference and publication in the IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. Within the past 25 years, Purdue researchers have published more than 30 papers in this journal, which is considered the flagship journal in chip design.

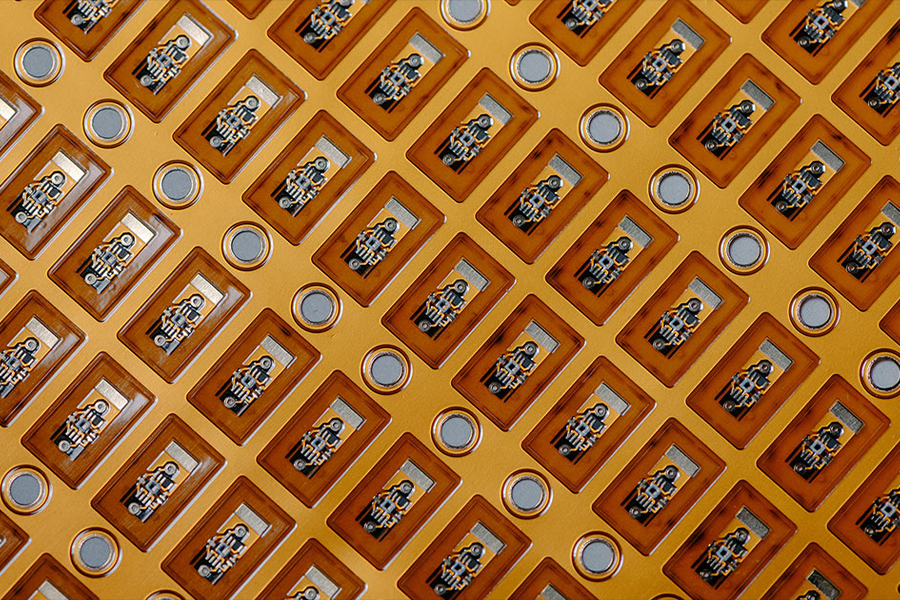

In recent years, 10 of those Purdue papers described chip designs from Sen’s lab. These chips include ones designed for transferring data at high speeds and ultra-low power levels, which are needed for using AI directly on wearable devices such as smartwatches.

This energy efficiency is possible because these chips allow wearable devices to create a network that mimics the human body’s nervous system.

A human’s nervous system has two main parts: the central nervous system, which includes the brain, and the peripheral nervous system, which has nerves that the brain uses to rapidly transmit information throughout the body. Even though the brain consumes more energy than most organs of the body, it offsets this energy use by maximizing the amount of information it transmits per unit of energy via the peripheral nervous system.

The wearable devices we use to access the internet, including AI algorithms over the cloud, have chips with “brains” in the form of central processing units, but no “nerves.” Without having something to function as a peripheral nervous system, these “brains” in wearable devices use high-energy electromagnetic waves such as Bluetooth or Wi-Fi to send information to each other, which limits the battery life of these devices and prevents them from having the capability to support complex AI algorithms on-chip.

The chip designs Sen’s lab has developed supply an artificial peripheral nervous system by transmitting information over lower-frequency signals. Using these signals, which are in the electro-quasistatic range on the electromagnetic spectrum, these chips can send data to each other 10 times faster than Bluetooth while consuming 100 times less energy per bit than Bluetooth or Wi-Fi. At ISSCC in 2022, Sen and his students presented a patent-pending chip design that uses electro-quasistatic signals to address problems with increasing the speed and energy efficiency of transferring video between wearable devices.

Toward designing chips that use AI without needing the whole internet

Sen and his collaborators have begun testing out how to incorporate AI algorithms into this high-speed, low-power chip design concept for wearable devices.

Among his papers published in the IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits, Sen has demonstrated patent-pending state-of-the-art chips that use AI algorithms in a method called “in-sensor analytics” to allow a wearable device to only interpret the data it needs to perform certain functions.

Let’s say you have an app on your smartphone that uses an electrocardiogram patch with an in-sensor analytics chip on your chest to notify you when you’re experiencing irregular heart activity, regardless of a good internet connection.

Even though the smartphone would have internet access as an edge device, the in-sensor analytics chip within the patch wouldn’t need constant internet access to use AI because these algorithms would have already been trained to only interpret irregular heart activity.

In addition to not having to worry about internet access, you also wouldn’t have to stress over keeping your wearable electrocardiogram charged thanks to a low-powered “peripheral nervous system” — in the form of electro-quasistatic signals — that connects your patch to your smartphone.

Sen envisions that other wearable devices ranging from smartwatches and smart glasses to implants could also tap into this network to do more with AI if equipped to transfer data using electro-quasistatic signals. Last year, Sen’s lab published initial results for a patent-pending implant concept it developed that was the first to demonstrate electro-quasistatic signal communication in the brain.

Although Sen hasn’t yet designed a chip for creating an AI-driven electrocardiogram patch, he is working on bringing to market a chip that might make that kind of application possible someday. In 2020, Sen, his students and other Purdue alumni founded a startup called Ixana to commercialize a patent-pending chip, “Wi-R,” that incorporates their designs inspired by the human body’s nervous system.

Sen and his team debuted Wi-R last year at CES, an annual technology show in Las Vegas. This year, the chip was named an honoree of two CES innovation awards. Ixana was also recently included in the Electronic Engineering Times’ annual list of 100 startups in the silicon industry to watch in 2024.

Through this startup and his continued published research, Sen is helping the tech industry figure out how to incorporate lessons from the human body into wearable AI devices.

“With custom-made chips, we could overcome the energy constraints of wearable devices that prevent them from using AI to solve increasingly complex problems,” Sen said. “This could lead to the development of devices that we aren’t able to imagine yet.”

The Purdue Innovates Office of Technology Commercialization has filed patent applications wherever applicable for Sen’s chip designs. Sen’s work in chip design has been partly funded by the National Science Foundation and more than 20 companies from multiple industries. The Elmore Family School of Electrical and Computer Engineering is one of Purdue’s computing departments, which are part of the Purdue Computes initiative. Sen also is a researcher in the Scalable Manufacturing of Aware & Responsive Thin Films Consortium at Purdue. This consortium is affiliated with the university’s Institute for Physical Artificial Intelligence.

Source: Inspired by the human body, engineer designs chips that could make wearable AI more energy efficient