Leveling the virtual playing field: ensuring the integrity of virtual cycling

Imagine going for a bike ride out in the beautiful countryside, where it is just you, your bike, and the world. The weather is perfect, and you are enjoying being active and outside, but you are missing the community you love riding with. Now, imagine having that same experience but in the comfort of your own home and with a community of other cyclists joining you from around the world in real-time, where you could either go for a leisurely ride or compete alongside the best of the best. Virtual cycling offers everyone this opportunity by allowing people to connect their bikes to a smart bike trainer, which brings them into a virtual world and provides a fully immersive experience where the athlete can leisurely ride, train, or race, while interacting with other cyclists from anywhere in the world. The virtual races have been designed to not only simulate a real racecourse, but also to require the same athletic fortitude. Today, virtual cycling is more than just a leisure sport or an alternative training method; it is a legitimate competition format recognized by the International Cycling Federation (UCI), which conducts competition events that include some of the top international cyclists. As we enter this new world of virtual cycling, where competitors may be anywhere in the world, how do we intentionally foster an environment that values integrity and builds up the credibility of this popular new competition format?

Virtual Cycling brings new challenges

The first big cycling race to be brought to the virtual world was the Tour of Flanders, part of the UCI 2020 World Tour. It took place at the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdowns, and fans and athletes alike were eager to engage in sporting events in whatever way they could. Having a high-profile race like this take place in a virtual environment induced a paradigm shift toward a broader acceptance of virtual sports as a legitimate competition platform; however, this brings the competition format and equipment under a higher level of scrutiny. After one of the first virtual events, riders noticed that the top finishers were all using the same bike trainer. Was this just a coincidence? Perhaps. But it affirmed the need for an independent certification process, or homologation process, to assure athletes, teams, and fans that the variety of trainers on the market perform comparably.

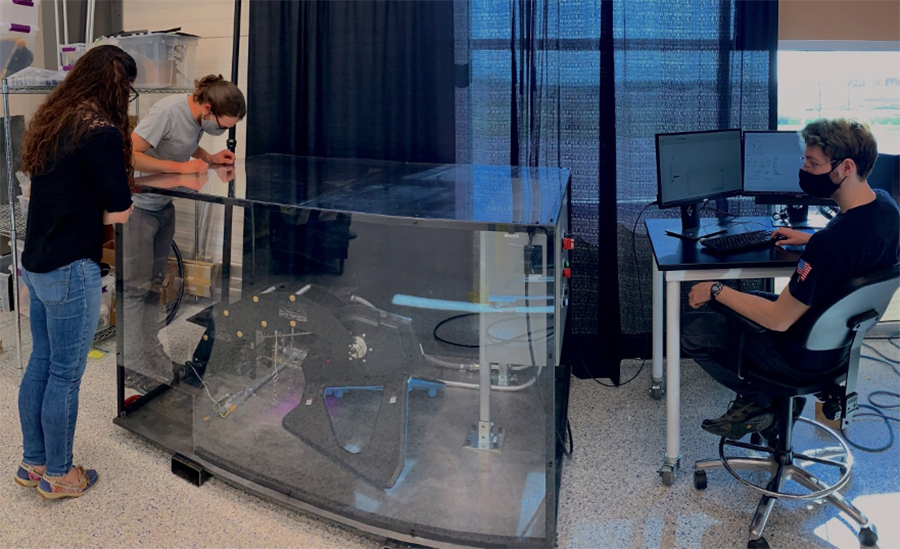

"When the lockdown suddenly started last year, we had two weeks to help organize the first-ever professional virtual cycling race with the Tour of Flanders. After that became such a spectacular success with younger TV audiences, the need for trainer homologation became clear, and this project was started at Purdue Ray Ewry Sports Engineering Center (RESEC),” says Wim Sweldens, co-founder and chief architect of Kiswe and senior advisor to RESEC. The team leading this trainer certification process, based at Purdue University, saw that virtual cycling was heading in this direction after the virtual Tour de Flanders, and began developing a device and methodology for characterizing smart trainer accuracy and behavior. This team is led by Jan-Anders Mansson, a Distinguished Professor of Engineering and the executive director of Purdue RESEC, and Sweldens, and includes the expertise and talents of three PhD candidates: Diana Heflin, Teal Dowd, and Justin Miller.

“Our team used all the latest digital technologies to create a homologation system for virtual cycling trainers that will level the playing field for every racecourse and will be implemented in the coming months,” says Mansson. Last week, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced the inaugural Olympic Virtual Series (OVS), a partnership with five International Sports Federations (IFs) and game publishers to produce the first-ever, Olympic-licensed event for physical and non-physical virtual sports. In the context of cycling, the IOC and UCI joined forces with Zwift to deliver the cycling component of the OVS. Held June 1-27, the OVS is positioned toward the broader cycling and sporting communities to encourage participation, inclusion and the sharing of the Olympic values and spirit. As virtual sports continue to become more popularized, it reaffirms the importance of having an established homologation process in place.

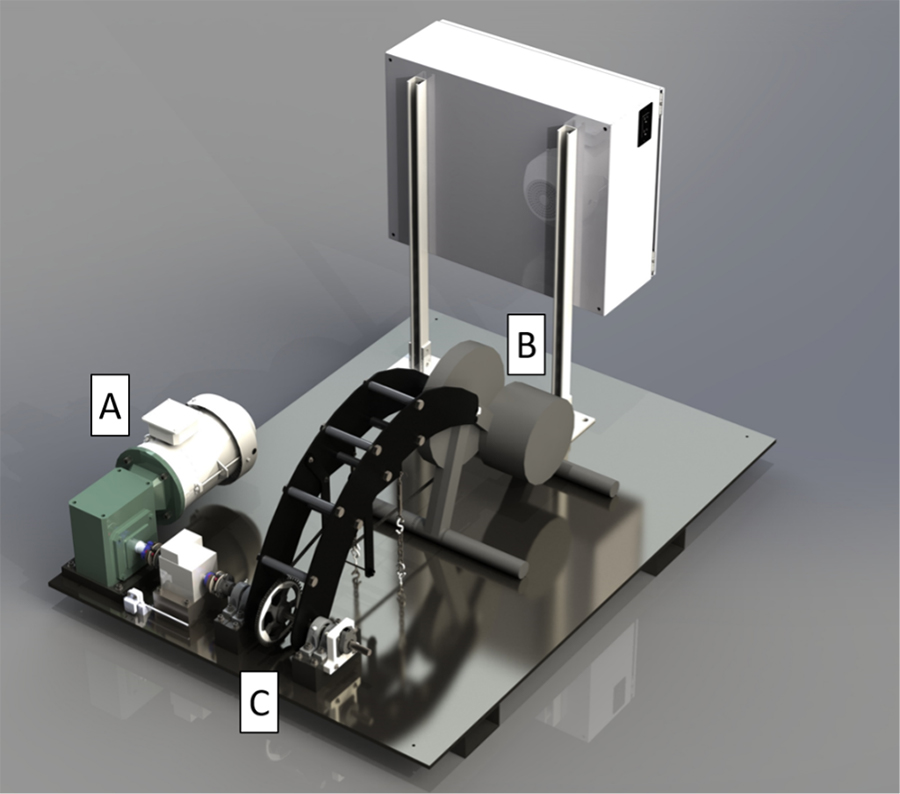

“We began with the fundamentals of the process: what data needs to be collected and with what accuracy. From there, we designed a testing apparatus able to test any major bike trainer on the market with sufficient accuracy to be a benchmark for even the most accurate trainers,” says Dowd, the lead design engineer on the project. He is a PhD candidate in materials engineering at Purdue with his undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering. “This system enables us to characterize and evaluate both the steady state and the dynamic attributes of any trainer. The trainer homologation system is set up as follows: Instead of an athlete, a motor is used to input a known power to the trainer and is connected to highly accurate torque and rotational measurement sensors. The drive motor is capable of producing power greater than any athlete so a full range of power can be tested,” adds Miller, a PhD candidate in aeronautical engineering at Purdue and a bike enthusiast who brings vital experience to the team.

This system provides data on how accurate different trainers are in various race situations. The accuracy of this data empowers competition hosts, like UCI, to make the best decisions about how to create a fair competition. Smart trainers measure the athlete’s power output, which then determines his or her avatar’s behavior on the virtual course. In addition to reacting to the athlete, the smart trainers are responsive to the race environment. Based on factors such as incline and wind resistance, the smart trainer modifies the resistance felt by athletes to simulate what they would experience if they were competing on the real course.

The road ahead

The team at Purdue is the first to have created a homologation system for virtual cycling. This accomplishment is a giant leap toward greater acceptance and future incorporation of the virtual racing format at the highest levels, such as the Olympics. “Purdue’s homologation system allows for an independent body to certify different bike trainers, to see which models are accurate and which ones may not be. Having this technology established is the next step toward furthering the legitimacy of the sport so that both fans and athletes trust that the results are purely from athletic ability and not from equipment error or tampering,” shares Heflin, a PhD candidate in materials engineering at Purdue. This sentiment is shared by the UCI and is a promising indicator of things to come.

“The future of virtual cycling, and the credibility of virtual cycling, is set on the foundation of fair competition. If people feel that they are not being part of something fair, then I think it is really hard for that sport to grow,” says Michael Rogers, Innovation Manager at UCI. With the younger generation exhibiting evolving interests and perspectives regarding sports compared to previous generations, event organizers and federations may have to consider the role virtual sports will play. These younger fans and athletes will likely “interact with the Olympic movement and the Olympic Games a little bit differently,” says Rogers, so for sports to not just survive but thrive, we must start looking at how virtual sports can be legitimized. And the first step is through assuring trust.

This article was produced by Purdue University for Games Flash, an internal emailer of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). As part of this collaboration, Purdue develops periodic content highlighting insights about the latest technologies sport globally. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the IOC.

Interview with Michael Rogers

Michael Rogers

Michael is inspired by high performing teams. As a professional cyclist, Michael enjoyed a successful career that spanned 16 years, during which he competed at 4 Olympic Games, became the first male cyclist in history to win 3 consecutive world time trial championships and won stages at the Tour de France and Tour of Italy. Since leaving the pro cycling world as a rider, Michael has continued to pursue his fascination with the factors that lead to becoming the best - whether that be as an entrepreneur or a leader in an established organization. Michael currently leads the Union Cyclist Internationale (World Cycling Federation) Innovation and Cycling Esports departments.

Michael lives in the Italian speaking area of Switzerland. When he is not working, he enjoys spending time with his wife and three daughters, walking his dogs, reading, and exploring topics ranging from current affairs, real estate, and finance. And of course, he still adores riding his bike.