Interns experience full process of needs-based medical device innovation in NIH-supported clinical immersion program

The experience is made possible by a five-year NIH grant designed to make senior design at the Weldon School translational and relevant to the real word.

“The senior design we do here is cutting edge,” said Ann Rundell, an associate professor of biomedical engineering and lead PI on the project. “By placing students in the clinical environment, we put them in the ideal position to identify real-world unmet clinical needs and brainstorm with clinicians. In senior design, they work with multidisciplinary teams to take their idea through the full biodesign process. So, they see a project move from needs identification in the clinic to the iterative design process in the classroom and ultimately into the clinical market.”

Awe-Inspiring Experience

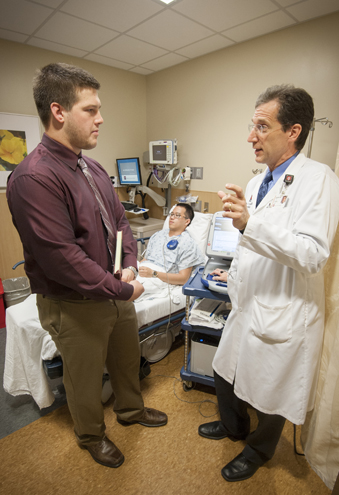

This year, one of the teams paired Weldon School senior Charles Ayres with Philip Krause (BSChE ’82, MD-IUSM), a cardiologist in Lafayette, IN.

Ayres shadowed Krause at the Lafayette Heart Institution and the IU Health Arnett Hospital. He observed Krause meeting with patients for standard device check-ups, consultations, and treatment plans. Ayres learned to operate the programming devices for the pacemakers and performed interrogations of these devices. This deepened his knowledge of pacemaker lead connections, battery life, and how cardiac events are recorded. At the hospital, Ayers observed implant procedures, such as charge generator changes and full device implants.

“Every day that I went in I learned something,” said Ayres. “When we slowed down someone’s heart and they are dependent upon a pacemaker, it was potentially a life-altering procedure. That was an awe-inspiring experience…Simply being present in the operating room was an amazing experience.”

As an intern, he was impressed by the teamwork, skill, and calm demonstrated by Krause and his team during tedious procedures. As an engineer, his attention was held by a procedure in which a lead is inserted into the subclavian vein and then run to its intended location on the heart. “Keep in mind that this is done by touch and brief captures on an x-ray that show the position of the wire against a gray background of tissue,” Ayres said.

It was easy to read the unspoken question in his mind: Could there be a better way to do this?

“My work with Dr. Krause showed me that there is always room for improving medical care; it is our task as engineers to solve these problems and provide physicians and patients alike with the tools necessary to improve the efficacy of treatment.”

Reciprocating Value

This was not Krause’s first experience as a mentor, and not the first time he worked with an inquisitive student who challenged the status quo. Two years ago he worked with then-senior Johnny Zhang who returned from his internship with Krause with an idea that he and his senior design team developed into the SafePace, currently a patent-pending product.

“Johnny asked, ‘What is the toughest thing about implanting a pacemaker,’” recalled Krause. “I said, ‘It’s getting the lead in the right position. Sometimes we try to decide whether it’s hooked in strong enough by pulling on it.’ Johnny said, ‘Well, that doesn’t sound too scientific. Can we do something scientific about the attachment of the lead and the tug that you do, like a little calibrated tug?’ And that’s when we came up with the idea of a calibrated tug, and the SafePace was born. It was an idea as simple as that, that led to a really nice project.”

Krause enjoyed the experience so much he volunteered for another round.

“It’s been good for me to be reminded what engineers think about. It’s amazing the questions they come up with and the insight they have. There is a whole thinking process in engineering that may not exist all the time in medicine.”

The internships are valuable for Krause as well. “Once an engineer, always an engineer,” he quipped. “I always think about projects or ideas that I don’t have time to investigate on my own.” This program gives him the opportunity to discuss ideas with the students. Ultimately an idea or two sticks, and a senior design project begins.

Promising Projects

This year Krause and Ayres zeroed in on challenges associated with pacemakers, such as testing the battery of a pacemaker, identifying the pacemaker through x-ray, and the telemedicine aspect of pacemakers. Two of their ideas eventually became senior design projects: improving the accuracy of activity-appropriate pacing and the pacemaker monitoring systems for physicians.

Ayres was motivated by personal reasons to opt for a project that focuses on preventing restenosis and promoting reendothelialization of vascular walls after a stenting procedure. “My grandmother was suffering from a large aortic aneurysm in which complications eventually led to her passing,” he said, noting that his grandmother passed away in the middle of his summer internship. “These factors led me to the final decision of choosing which senior design project I wanted to work on.”

The project went well, he said, but was challenging. “It’s an eye opening experience that really exposes you to all the finer details of researching and developing a product…I definitely have developed an appreciation for everything that goes into getting an innovation from concept to an approved medical device. It’s fascinating to look at a product now and think about all that went into getting it in your physician’s hands.”

Lasting Lessons

The notebook Ayres filled during his internship has been shelved, but the education he gained from the experience will last a lifetime. “The NIH internship was phenomenal. The knowledge I gained in proper conduct and the overall care process is invaluable. I can’t thank Dr. Krause enough for all the time he spent with me explaining everything from a decision on prescriptions to how a dilator gets a lead into a vessel. He is a phenomenal mentor and friend, and I do miss our coffee break talks between patient visits.”

Along with Rundell, the project is led by co-PIs Pedro Irazoqui, associate head, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering; Alyssa Panitch, Leslie A. Geddes Professor of Biomedical Engineering; Kinam Park, Showalter Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering; Sherry Voytik Harbin, associate professor, School of Biomedical Engineering; and collaborator Andrew Brightman, assistant head, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering and associate professor, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering.

The PI and co-PIs express their appreciation to the NIH for funding this project: “A Multidisciplinary and Needs-Driven Approach to Translational Team-Based Biomedical Engineering Design,” R25 grant #410200008000042143.

Top 3 photos: Dr. Philip Krause and former Weldon School intern Charles Ayres.

Bottom photo: Former interns in the NIH-sponsored Clinical Internship Program returned to the Weldon School for a mid-internship review of their clinical experiences. The team met with faculty members to discuss ideas for potential senior design projects that they identified as real clinical needs at the facilities they are interning for. Pictured: Hilary Schroeder, Nick Braun, Eric Miller, Jim McCarthy, and Lauren Gilliland. Not pictured: Charles Ayres.