Zope Services

Some Zope objects are service objects. Service objects provide various kinds of support to your "domain-specific" content, logic, and presentation objects. They help solve fundamental problems that many others have experienced when writing applications in Zope.

Access Rule Services

Access Rules make it possible to cause an action to happen any time a user "traverses" a Folder in your Zope site. When a user's browser submits a request for a URL to Zope which has a Folder's name in it, the Folder is "looked up" by Zope during object publishing. That action (the lookup) is called traversal. Access Rules are arbitrary bits of code which effect the environment in some way during Folder traversal. They are easiest to explain by way of an example.

In your Zope site, create a Folder named "accessrule_test". Inside the accessrule_test folder, create a Script (Python) object named access_rule with two parameters: container and request. Give the access_rule Script (Python) the following body:

useragent = request.get('HTTP_USER_AGENT', '') if useragent.find('Windows') != -1: request.set('OS', 'Windows') elif useragent.find('Linux') != -1: request.set('OS', 'Linux') else: request.set('OS', 'Non-Windows, Non-Linux')

This Script causes the traversal of the accessrule_test folder to cause a new variable named OS to be entered into the REQUEST, which has a value of Windows, Linux, or 'Non-Windows, Non-Linux' depending on the user's browser.

Save the access_rule script and revisit the accessrule_test folder's Contents view. Choose Set Access Rule from the add list. In the Rule Id form field, type access_rule. Then click Set Rule. A confirmation screen appears claiming that "'access_rule' is now the Access Rule for this object". Click "OK". Notice that the icon for the access_rule Script (Python) has changed, denoting that it is now the access rule for this Folder.

Create a DTML Method named test in the accessrule_test folder with the following body:

<dtml-var standard_html_header> <dtml-var REQUEST> <dtml-var standard_html_footer>

Save the test DTML Method and click its "View" tab. You will see a representation of all the variables that exist in the REQUEST. Note that in the other category, there is now a variable named "OS" with (depending on your browser platform) either Windows, Linux or 'Non-Linux, Non-Windows').

Revisit the accessrule_test folder and again select Set Access Rule from the add list. Click the No Access Rule button. A confirmation screen will be displayed stating that the object now has no Access Rule.

Visit the test script you created previously and click its View tab. You will notice that there is now no "OS" variable listed in the request because we've turned off the Access Rule capability for access_rule.

Access Rules don't need to be Script (Python) objects, they may also be DTML Methods or External Methods.

Temporary Storage Services

Temporary Folders are Zope folders that are used for storing objects temporarily. Temporary Folders acts almost exactly like a regular Folder with two significant differences:

- Everything contained in a Temporary Folder disappears when you restart Zope. (A Temporary Folder's contents are stored in RAM).

- You cannot undo actions taken to objects stored a Temporary Folder.

By default there is a Temporary Folder in your root folder named temp_folder. You may notice that there is an object entitled, "Session Data Container" within temp_folder. This is an object used by Zope's default sessioning system configuration. See the "Using Sessions" section later in this chapter for more information about sessions.

Temporary folders store their contents in RAM rather than in the Zope database. This makes them appropriate for storing small objects that receive lots of writes, such as session data. However, it's a bad idea use temporary folders to store large objects because your computer can potentially run out of RAM as a result.

Version Services

Version objects help coordinate the work of many people on the same set of objects. While you are editing a document, someone else can be editing another document at the same time. In a large Zope site hundreds or even thousands of people can be using Zope simultaneously. For the most part this works well, but problems can occur. For example, two people might edit the same document at the same time. When the first person finishes their changes they are saved in Zope. When the second person finishes their changes they over write the first person's changes. You can always work around this problem using Undo and History, but it can still be a problem. To solve this problem, Zope has Version objects.

Another problem that you may encounter is that you may wish to make some changes, but you may not want to make them public until you are done. For example, suppose you want to change the menu structure of your site. You don't want to work on these changes while folks are using your site because it may break the navigation system temporarily while you're working.

Versions are a way of making private changes in Zope. You can make changes to many different documents without other people seeing them. When you decide that you are done you can choose to make your changes public, or discard them. You can work in a Version for as long as you wish. For example it may take you a week to put the finishing touches on your new menu system. Once you're done you can make all your changes live at once by committing the version.

NOTE: Using versions via the Zope Management Interface requires that your browser supports and accepts cookies from the Zope server.

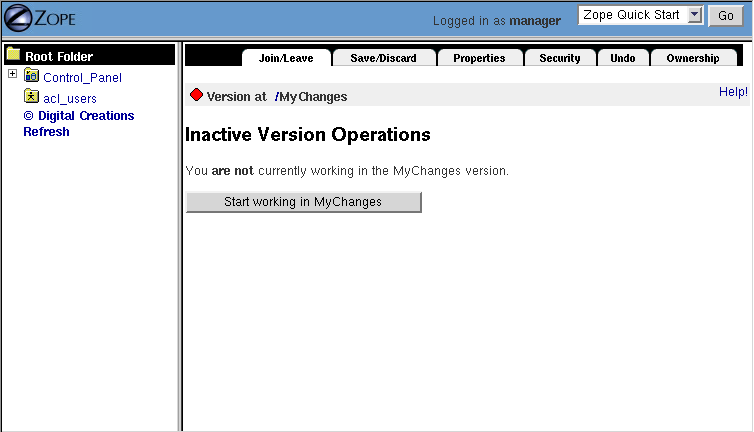

Create a Version by choosing Version from the product add list. You should be taken to an add form. Give your Version an id of MyChanges and click the Add button. Now you have created a version, but you are not yet using it. To use your version click on it. You should be taken to the Join/Leave view of your version as shown in the figure below.

Figure 6-1 Joining a Version

The Version is telling you that you are not currently using it. Click on the Start Working in MyChanges button. Now Zope should tell you that you are working in a version. Now return to the root folder. Notice that everywhere you go you see a small message at the top of the screen that says You are currently working in version /MyChanges. This message lets you know that any changes you make at this point will not be public, but will be stored in your version. For example, create a new DTML Document named new. Notice how it has a small red diamond after its id. Now edit your standard_html_header method. Add a line to it like so:

<HTML> <HEAD> <TITLE><dtml-var title_or_id></TITLE> </HEAD> <BODY BGCOLOR="#FFFFFF"> <H1>Changed in a Version</H1>

Any object that you create or edit while working in a version will be marked with a red diamond. Now return to your version and click the Quit working in MyChanges button. Now try to return to the new document. Notice that the document you created while in your version has now disappeared. Any other changes that you made in the version are also gone. Notice how your standard_html_header method now has a small red diamond and a lock symbol after it. This indicates that this object has been changed in a version. Changing an object in a version locks it, so no one else can change it until you commit or discard the changes you made in your version. Locking ensures that your version changes don't overwrite changes that other people make while you're working in a version. So for example if you want to make sure that only you are working on an object at a given time you can change it in a version. In addition to protecting you from unexpected changes, locking also makes things inconvenient if you want to edit something that is locked by someone else. It's a good idea to limit your use of versions to avoid locking other people out of making changes to objects.

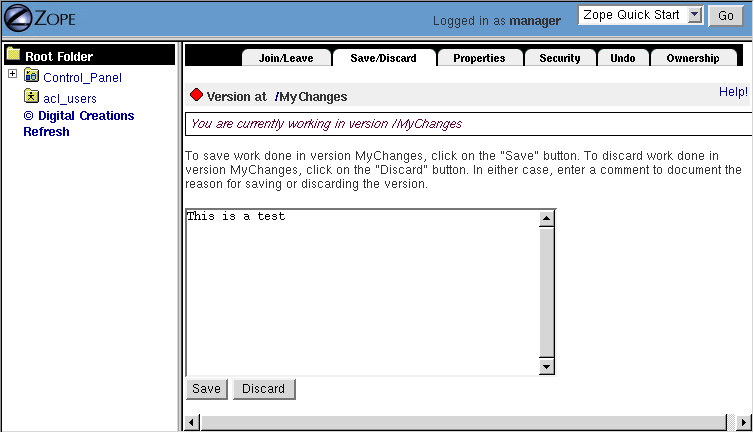

Now return to your version by clicking on it and then clicking the Start working in MyChanges button. Notice how everything returns to the way it was when you left the Version. At this point let's make your changes permanent. Go to the Save/Discard view as shown in the figure below.

Figure 6-2 Committing Version changes.

Enter a comment like This is a test into the comment field and click the Save button. Your changes are now public, and all objects that you changed in your Version are now unlocked. Notice that you are still working in your Version. Go to the Join/Leave view and click the Quit Working in MyChanges button. Now verify that the document you created in your version is visible. Your change to the standard_html_header should also be visible. Like anything else in Zope you can choose to undo these changes if you want. Go to the Undo view. Notice that instead of many transactions one for each change, you only have one transaction for all the changes you made in your version. If you undo the transaction, all the changes you made in the version will be undone.

Versions are a powerful tool for group collaboration. You don't have to run a live server and a test server since versions let you make experiments, evaluate them and then make them public when you decide that all is well. You are not limited to working in a version alone. Many people can work in the same version. This way you can collaborate on version's changes together, while keeping the changes hidden from the general public.

Caveat: Versions and ZCatalog

ZCatalog is Zope's indexing and searching engine, covered in depth in the chapter entitled Searching and Categorizing Content.

Unfortunately, Versions don't work well with ZCatalog. This is because versions lock objects when they are modified in a version, preventing changes outside the version.

ZCatalog has a way of connecting changes made to disparate objects. This is because cataloging an object must, by necessity change the catalog. Objects that automatically catalog themselves when they are changed propagate their changes to the catalog. If such an object is changed in a version, then the catalog is changed in the version too, thus locking the catalog itself. This makes the catalog and versions get along poorly. As a rule, versions should not be used in applications that use the catalog.

Caching Services

A cache is a temporary place to store information that you access frequently. The reason for using a cache is speed. Any kind of dynamic content, like a DTML page or a Script (Python), must be evaluated each time it is called. For simple pages or quick scripts, this is usually not a problem. For very complex DTML pages or scripts that do a lot of computation or call remote servers, accessing that page or script could take more than a trivial amount of time. Both DTML and Python can get this complex, especially if you use lots of looping (such as the in tag or the Python for loop) or if you call lots of scripts, that in turn call lots of scripts, and so on. Computations that take a lot of time are said to be expensive.

A cache can add a lot of speed to your site by calling an expensive page or script once and storing the result of that call so that it can be reused. The very first person to call that page will get the usual "slow" response time, but then once the value of the computation is stored in the cache, all subsequent users to call that page will see a very quick response time because they are getting the cached copy of the result and not actually going through the same expensive computation the first user went through.

To give you an idea of how caches can improve your site speed, imagine that you are creating www.zopezoo.org, and that the very first page of your site is very complex. Let's suppose this page has complex headers, footers, queries several different database tables, and calls several special scripts that parse the results of the database queries in complex ways. Every time a user comes to www.zopezoo.org, Zope must render this very complex page. For the purposes of demonstration, let's suppose this complex page takes one-half of a second, or 500 milliseconds, to compute.

Given that it takes a half of a second to render this fictional complex main page, your machine can only really serve 120 hits per minute. In reality, this number would probably be even lower than that, because Zope has to do other things in addition to just serving up this main page. Now, imagine that you set this page up to be cached. Since none of the expensive computation needs to be done to show the cached copy of the page, many more users could see the main page. If it takes, for example, 10 milliseconds to show a cached page, then this page is being served 50 times faster to your web site visitors. The actual performance of the cache and Zope depends a lot on your computer and your application, but this example gives you an idea of how caching can speed up your web site quite a bit. There are some disadvantages to caching however:

- Cache lifetime

- If pages are cached for a long time, they may not reflect the most current information on your site. If you have information that changes very quickly, caching may hide the new information from your users because the cached copy contains the old information. How long a result remains cached is called the cache lifetime of the information.

- Personal information

- Many web pages may be personalized for one particular user. Obviously, caching this information and showing it to another user would be bad due to privacy concerns, and because the other user would not be getting information about them, they'd be getting it about someone else. For this reason, caching is often never used for personalized information.

Zope allows you to get around these problems by setting up a cache policy. The cache policy allows you to control how content gets cached. Cache policies are controlled by Cache Manager objects.

Adding a Cache Manager

Cache managers can be added just like any other Zope object. Currently Zope comes with two kinds of cache managers:

- HTTP Accelerated Cache Manager

- An HTTP Accelerated Cache Manager allows you to control an HTTP cache server that is external to Zope, for example, Squid. HTTP Accelerated Cache Managers do not do the caching themselves, but rather set special HTTP headers that tell an external cache server what to cache. Setting up an external caching server like Squid is beyond the scope of this book, see the Squid site for more details.

- (RAM) Cache Manager

- A RAM Cache Manager is a Zope cache manager that caches the content of objects in your computer memory. This makes it very fast, but also causes Zope to consume more of your computer's memory. A RAM Cache Manager does not require any external resources like a Squid server, to work.

For the purposes of this example, create a RAM Cache Manager in the root folder called CacheManager. This is going to be the cache manager object for your whole site.

Now, you can click on CacheManager and see its configuration screen. There are a number of elements on this screen:

- Title

- The title of the cache manager. This is optional.

- REQUEST variables

- This information is used to store the cached copy of a page. This is an advanced feature, for now, you can leave this set to just "AUTHENTICATED_USER".

- Threshold Entries

- The number of objects the cache manager will cache at one time.

- Cleanup Interval

- The lifetime of cached results.

For now, leave all of these entries as is, they are good, reasonable defaults. That's all there is to setting up a cache manager!

There are a couple more views on a cache manager that you may find useful. The first is the Statistics view. This view shows you the number of cache "hits" and "misses" to tell you how effective your caching is.

There is also an Associate view that allows you to associate a specific type or types of Zope objects with a particular cache manager. For example, you may only want your cache manager to cache DTML Documents. You can change these settings on the Associate view.

At this point, nothing is cached yet, you have just created a cache manager. The next section explains how you can cache the contents of actual documents.

Caching an Object

Caching any sort of cacheable object is fairly straightforward. First, before you can cache an object you must have a cache manager like the one you created in the previous section.

To cache a document, create a new DTML Document object in the root folder called Weather. This object will contain some weather information. For example, let's say it contains:

<dtml-var standard_html_header> <p>Yesterday it rained.</p> <dtml-var standard_html_footer>

Now, click on the Weather DTML Document and click on its Cache view. This view lets you associate this document with a cache manager. If you pull down the select box at the top of the view, you'll see the cache manager you created in the previous section, CacheManager. Select this as the cache manager for Weather.

Now, whenever anyone visits the Weather document, they will get the cached copy instead. For a document as trivial as our Weather example, this is not much of a benefit. But imagine for a moment that Weather contained some database queries. For example:

<dtml-var standard_html_header> <p>Yesterday's weather was <dtml-var yesterdayQuery> </p> <p>The current temperature is <dtml-var currentTempQuery></p> <dtml-var standard_html_footer>

Let's suppose that yesterdayQuery and currentTempQuery are SQL Methods that query a database for yesterdays forecast and the current temperature, respectively (for more information on SQL Methods, see the chapter entitled Relational Database Connectivity.) Let's also suppose that the information in the database only changes once every hour.

Now, without caching, the Weather document would query the database every time it was viewed. If the Weather document was viewed hundreds of times in an hour, then all of those hundreds of queries would always contain the same information.

If you specify that the document should be cached, however, then the document will only make the query when the cache expires. The default cache time is 300 seconds (5 minutes), so setting this document up to be cached will save you 91% of your database queries by doing them only one twelfth as often. There is a trade-off with this method, there is a chance that the data may be five minutes out of date, but this is usually an acceptable compromise.

Outbound Mail Services

Zope comes with an object that is used to send outbound e-mail, usually in conjunction with the DTML sendmail tag, described more in the chapter entitled Variables and Advanced DTML.

Mailhosts can be used from either Python or DTML to send an email message over the Internet. They are useful as gateways out to the world. Each mailhost object is associated with one mail server, for example, you can associate a mailhost object with yourmail.yourdomain.com, which would be your outbound SMTP mail server. Once you associate a server with a mailhost object, the mailhost object will always use that server to send mail.

To create a mailhost object select MailHost from the add list. You can see that the default id is "MailHost" and the default SMTP server and port are "localhost" and "25". make sure that either your localhost machine is running a mail server, or change "localhost" to be the name of your outgoing SMTP server.

Now you can use the new MailHost object from a DTML sendmail tag. This is explained in more detail in the chapter entitled Variables and Advanced DTML, but we provide a simple example below. In your root folder, create a DTML Method named send_mail with a body that looks like the following:

<dtml-sendmail> From: me@nowhere.com To: you@nowhere.com Subject: Stop the madness! Take a day off, you need it. </dtml-sendmail>

Ensure that all the lines are flush against the left side of the textarea for proper function. When you invoke this DTML Method (perhaps by visiting its View tab), it will use your newly-created MailHost to send an admonishing mail to "you@nowhere.com". Substitute your own email address to try it out.

The API for MailHost objects also allows you to send mail from Script (Python) objects and External Methods. See the Zope MailHost API in the Zope help system at Zope Help -> API Reference -> MailHost for more information about the interface it provides.

Error Logging Services

The Site Error Log object, typically accessible in the Zope root under the name error_log, provides debugging and error logging information in real-time. When your site encounters an error, it will be logged in the Site Error Log, allowing you to review (and hopefully fix!) the error.

Options settable on a Site Error Log instance include:

- Number of exceptions to keep

- keep 20 exceptions by default, rotating "old" exceptions out when more than 20 are stored. Set this to a higher or lower number as you like.

- Copy exceptions to the event log

- If this option is selected, the site error log object will copy the text of exceptions that it receives to the "event log" facility, which is typically controlled by the

EVENT_LOG_FILEenvironment variable. For more information about this environment variable, see the chapter entitled Installing and Starting Zope.

Virtual Hosting Services

For detailed information about using virtual hosting services in Zope, see the chapter entitled Virtual Hosting Services.

Searching and Indexing Services

For detailed information about using searching and indexing services in Zope to index and search a collection of documents, see the chapter entitled Searching and Categorizing Content.

Sessioning Services

For detailed information about using Zope's "sessioning" services to "keep state" between HTTP requests for anonymous users, see the chapter entitled Sessions.

Internationalization Services

This section of the document needs to be expanded. For now, please see documentation for Zope 2.6+ wrt Unicode and object publishing at http://old.zope.org/Members/htrd/howto/unicode-zdg-changes and http://old.zope.org/Members/htrd/howto/unicode .