Purdue researchers uncover new behavior in quantum light–matter systems

A Purdue-led research team has uncovered how to stabilize a notoriously unstable quantum system, opening new possibilities for technologies that rely on precise control of light and matter at the quantum level.

The study, published in Physical Review Letters, investigates what happens when many atoms interact with light inside a cavity. This is a fundamental model in quantum physics known as the Dicke model. While the standard version of this model has been explored for decades, the Purdue team examined a far more complex variation where atoms interact with pairs of photons at a time, instead of just one.

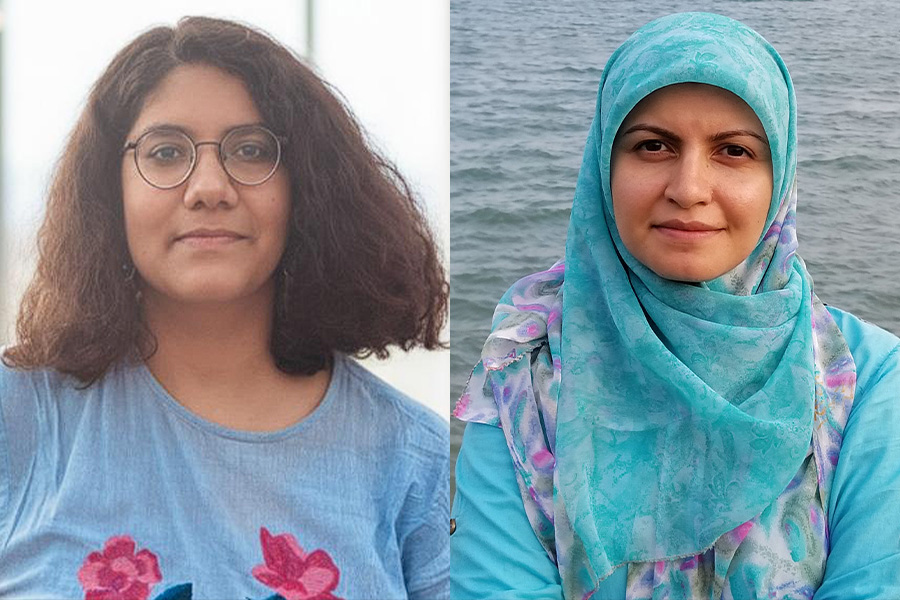

The first author on the paper, Aanal Jayesh Shah, is a PhD student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy whose advisor is Hadiseh Alaeian, assistant professor in both the Elmore Family School of Electrical Engineering and the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

Understanding a tricky quantum system

In its two-photon version, the Dicke model predicts exotic behavior, including “superradiance,” where atoms collectively emit light much more intensely than they would individually. But there’s a problem: in the real world, this system tends to become unstable. Instead of settling into a steady state, the light intensity spirals upward without limit.

The team found that adding the right kind of energy loss, specifically, two-photon loss, where photons leave the cavity in pairs, prevents the system from blowing up. This extra loss mechanism allows the system to stabilize and reveal its underlying quantum phases.

“By showing that two-photon loss can bring the system back under control, we were able to uncover the rich phases that were previously hidden,” said Shah. “It’s exciting to find a simple mechanism that makes this complex quantum behavior experimentally accessible.”

A new look at quantum phase transitions

Using a combination of analytical equations and numerical simulations, the researchers showed that introducing two-photon loss leads to a dissipative phase transition. In simple terms, the system can switch between:

- a normal state, where almost no light is present, and

- a superradiant state, where the atoms and light synchronize and produce a large, stable photon population and ordered atom ensemble.

Uniquely, the team found that these states can coexist, meaning the system can settle into either one depending on atom-light coupling strength. This coexistence is a hallmark of a first-order phase transition, like how water and ice can coexist at 32°F.

Visualizations from the study, including Wigner functions (a type of quantum phase-space map), show this structure and a striking fourfold symmetry (called Z symmetry) in the superradiant state — a signature of the underlying two-photon processes.

Why it matters

Understanding and controlling dissipative phase transitions is essential for emerging quantum technologies, including:

- quantum sensors that detect tiny changes in fields or forces,

- quantum batteries that store energy at the quantum limit,

- cat-qubit systems used in error-corrected quantum computing, and

- nonlinear photonic platforms that rely on strong, engineered interactions between light and matter.

“Understanding how to stabilize and control these nonlinear quantum systems opens the door to a wide range of applications, from quantum sensing to next-generation photonic devices,” said Alaeian. “I’m incredibly proud of the creativity and persistence Aanal brought to this project.”

By showing how two-photon loss stabilizes this complex system, the Purdue-led team provides a roadmap for building experimental platforms that harness these effects.

Co-authors from the University of Strathclyde and institutions in Rome contributed to the study. The research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Quantum is a part of Purdue Computes — a comprehensive initiative that spans computing departments, physical AI, quantum science and semiconductor innovation.