Engineering critical solutions for the opioid epidemic

“The current opioid crisis is not someone else’s problem, but ours,” wrote Kinam Park, Showalter Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Pharmacy at Purdue, in a cover story for the Journal of Controlled Release. “Having a potential solution alone is not enough. We all need to work together to bring what might be a potential solution to what will be used clinically.”

“The current opioid crisis is not someone else’s problem, but ours,” wrote Kinam Park, Showalter Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Pharmacy at Purdue, in a cover story for the Journal of Controlled Release. “Having a potential solution alone is not enough. We all need to work together to bring what might be a potential solution to what will be used clinically.”

Purdue is answering the call by marshalling efforts across the university and with industrial and clinical partners to develop and translate innovative solutions and engage communities in implementing the most effective set of interventions. Ranging from minimally invasive medical devices and injectables to be used in the body to engineered systems for community providers that can be used on the street, at home, or in the clinic, Purdue is investigating every touch point along the arc of the crisis, developing and implementing novel approaches to treat addiction, prevent overdose, and ease the transition to recovery.

Medical devices and injectables for the prevention of overdose and treatment of addiction

The Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering at Purdue is covering all aspects of treating opioid addiction ranging from long-acting drug formations to implantable and wearable electronic systems for the rapid detection of drug abuse and prevention of overdose.

In the realm of treating opioid addiction, Park and his team are developing an injectable, long-acting naltrexone release formulation that lasts more than two months after a single shot. It is affordable, patient friendly, and, importantly, is a time-released formula that can be injected into the body while opioids are still present, which means detox is not required before treatment can begin. The NIH recently awarded Park a $2.9M grant for the first two years to optimize and advance the formulation. Purdue Research Foundation filed a patent this month and Park and co-investigators plan to develop a roadmap for clinical trials next year.

Luis Solorio, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and Yoon Yeo, professor of industrial and physical pharmacy and biomedical engineering, recently received a NIDA R21 to address opioid abuse. They are collaborating on the development of an abuse deterrent formulation designed to counteract various ways that pills can be processed improperly, thereby preventing unintentional overdoses.

Multiple minimally invasive devices are also being developed at the Weldon School to help patients overcome addiction. Jacqueline Linnes, Marta E. Gross Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering, is working on a biosensor that could be used to detect drug concentrations in sweat. She is also developing a Smartwatch that monitors respiration and heart rate and could eventually be used to detect an overdose and place a call for help. A US patent has been filed for the Smartwatch, and Linnes is developing additional functionality, including blood oxygenation and electrodermal activity monitoring.

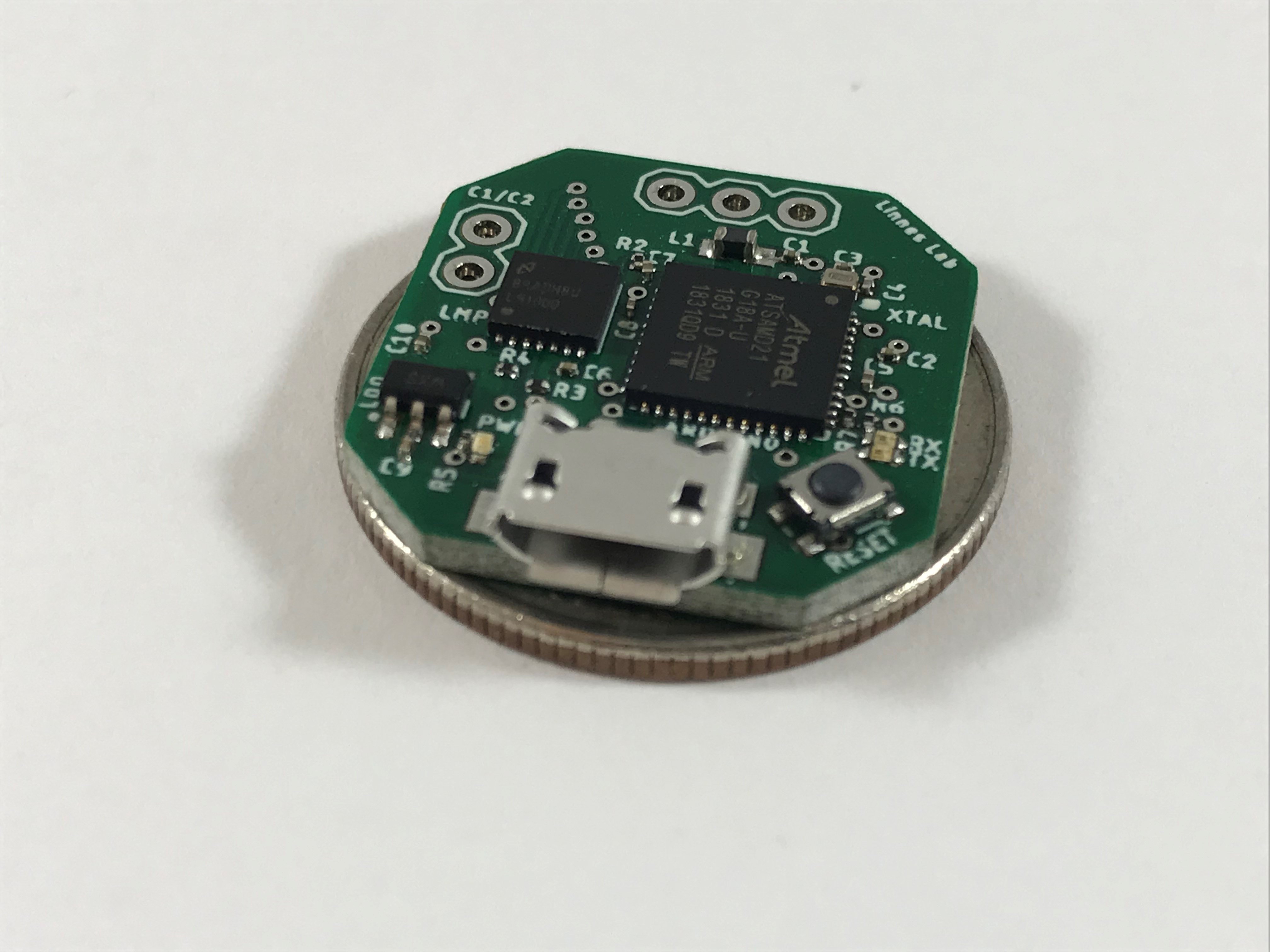

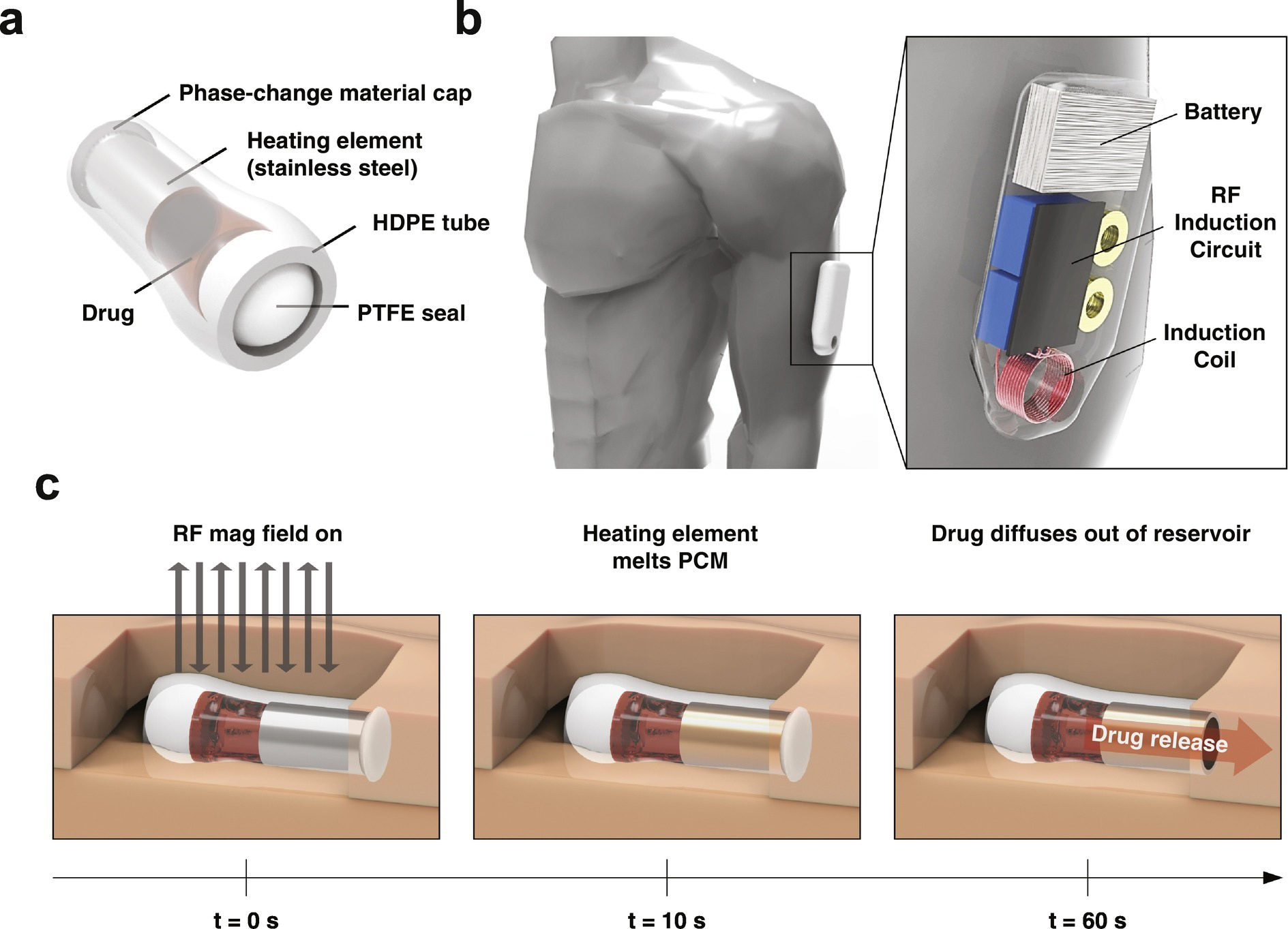

One floor down from the Linnes Lab, Hyowon “Hugh” Lee, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, is developing a wearable, minimally invasive device that would automatically detect an overdose and deliver naloxone, a drug that is administered as an antidote to overdose. “The antidote is always going to be with you,” said Lee. “The device wouldn’t require you to recognize that you’re having an overdose or to inject yourself with naloxone, keeping you stable long enough for emergency services to arrive.” Lee plans to develop communication capabilities and multidose applications for the device and has founded with colleagues the startup, Rescue Biomedical, LLC, to explore the market potential.

Modeling a set of interventions to support community coordination of treatment

The Regenstrief Center for Healthcare Engineering (RCHE) functions as an institutional hub for opioid treatment programs and champions Purdue’s multidisciplinary capabilities to statewide partners.

Through a $12M grant from the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA), Purdue Healthcare Advisors, RCHE’s nonprofit outreach arm, along with Purdue faculty from the Weldon School and several other colleges, are employing information technology, system and predictive analytics, and grass-roots programs to advance coordination of opioid addition treatment in two Indiana communities hard-hit by the crisis. In Fort Wayne, where infant mortality is 24 per thousand births, the team is addressing the high incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome. In Greater Lafayette, the focus is on improving the transition to treatment and recovery.

“We are looking at a set of interventions,” said RCHE Director Paul Griffin, professor of biomedical and industrial engineering, adding that “you can’t just fix the problem in one place.” The team is modeling interventions such as care options, technology systems, patient education, medication management, care transition, and clinical decision support, and working with providers in communities to prioritize and implement viable solutions.

Griffin and Nan Kong, associate professor of biomedical engineering, are engaged in this effort, along with faculty members from Purdue Colleges of Engineering, Health and Human Sciences, and Pharmacy.

Earlier this year, a $1.1M federal grant awarded to RCHE was earmarked for addressing the opioid crisis in Fayette County, Indiana, a community that has been disproportionately impacted by the opioid epidemic. The team is providing three years of guidance and technical support to the community using systems engineering to design novel approaches to such interventions as motivational interviewing techniques for providers and behavioral modification for patients.

“We are piloting this in three communities and doing formal evaluations,” said Griffin. “We are learning what makes a difference.” The next phase will be to extend successes across the State.

A comprehensive University-wide effort

Many more initiatives are underway at Purdue, including in the College of Pharmacy where researchers are studying alternative medicines for opioids and have discovered a nonaddictive drug compound that could replace opioids for chronic pain sufferers. That College also runs BoilerWORX, a RCHE co-sponsored initiative which brings first-response orientated services to Indiana communities. Services include naloxone training and distribution, drug disposal kit distribution, education and advocacy, and public policy advocacy.

Purdue Extension unites an array of community-based opioid prevention educational programs offered through Purdue’s Agriculture and Natural Resources, Health and Human Sciences, and Indiana 4-H Youth Development, to name a few. Programs include Mental Health First Aid and the Strengthening Families Program.

In a landmark review of the current state of the prevention of opioid abuse and treatment of opioid addiction, Park and co-author Andrew Otte, a research assistant professor and laboratory coordinator in the Chong Kun Dang Laboratory at the Weldon School, look to the future and call for a system-wide approach. “Finding a way to break through the current opioid epidemic crisis requires more than pharmaceutical and technical solutions…With the number of addicts and deaths increasing exponentially, the problem may soon affect everyone. An opioid addict is not merely someone on the street—it could be someone we know. We all should provide our support to help those battling addiction.”

Support is coming from Purdue engineers, scientists, and administrators working in labs, clinics, and communities around the State, and in collaboration with an array of clinical and industrial partners, to provide a comprehensive set of effective interventions toward extinguishing the opioid crisis.