Researchers track down “hidden” hearing loss

According to World Health Organization, over 466 million people worldwide—including 38 million Americans, live with disabling hearing loss. By 2050, it is predicted that nearly one in ten people will have hearing loss.

Research at Purdue suggests that number might be even higher.

“As many as 5-15% of adults who go to the clinic with trouble hearing turn out to have normal hearing thresholds,” said Hari Bharadwaj, assistant professor in the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering and assistant professor of speech, language and hearing sciences.

This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as “hidden” hearing loss because it is not detected by conventional testing, yet still causes considerable perceptual consequences that can vary widely from person to person.

Bharadwaj is leading a $1.25M NIH study to identify the causes of “hidden” hearing loss attributed to age and exposure to loud noise, and to pave the way for improved diagnostic markers.

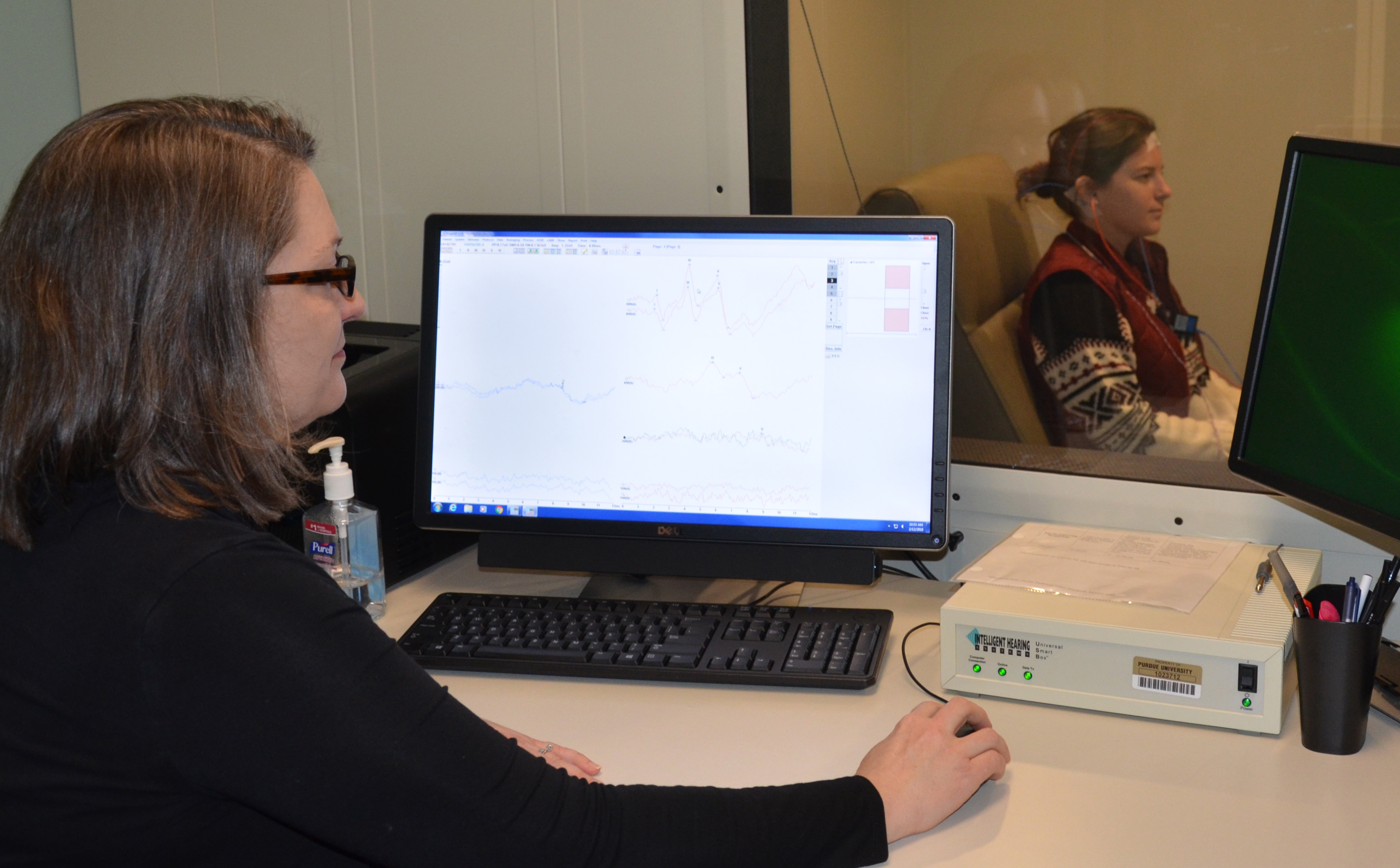

He is joined on the study by Purdue colleagues Jennifer Simpson, clinical professor and director of Clinical Education in Audiology and Michael Heinz, professor in the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering and professor of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences.

Conventional clinical hearing tests detect hearing loss by looking at the faintest sound that a patient can hear. However, Bharadwaj noted, sounds carry different kinds of information to the nerve fibers in the inner ear, not just volume.

When someone is speaking, for example, the sound includes various acoustical elements, such as the pitch of the voice and the distinct sounds of words, all packaged temporally. A person complaining of difficulty hearing might hear the sound, but not the details of the sound, especially in a noisy environment like a restaurant.

Previous animal studies conducted at Purdue and elsewhere may point to a piece of the puzzle. When animal test subjects are older or exposed to noise, they may exhibit a “hidden” hearing loss similar to that of humans. They test at normal hearing thresholds, but have difficulty hearing in noisy environments. In some of these animals, a microscopic look at the inner ear reveals a 40-50% loss of nerve fibers.

It’s these auditory nerve fibers that convert sounds into electric impulses that are interpreted in the brain. The loss of nerve fibers results in less detail about the sound carried to the brain, reducing the ability to hear sound, but not all the elements of the sound.

This may manifest as hearing someone speaking, but not being able to discern distinct words.

The researchers postulate that if humans show a cochlear neuropathy similar to animals that have this loss of nerve fibers, this could contribute to the “hidden” hearing loss. The next step would be identifying parallel diagnostic markers between animals and humans.

“We are coming at this from a couple of different angles,” said Simpson, referring to the transdisciplinary vision of the grant. “The study is a collaboration between a clinical audiologist with 20 years in the field and engineers who specialize in hearing science, from the patient care aspect to the engineering and science aspect.”

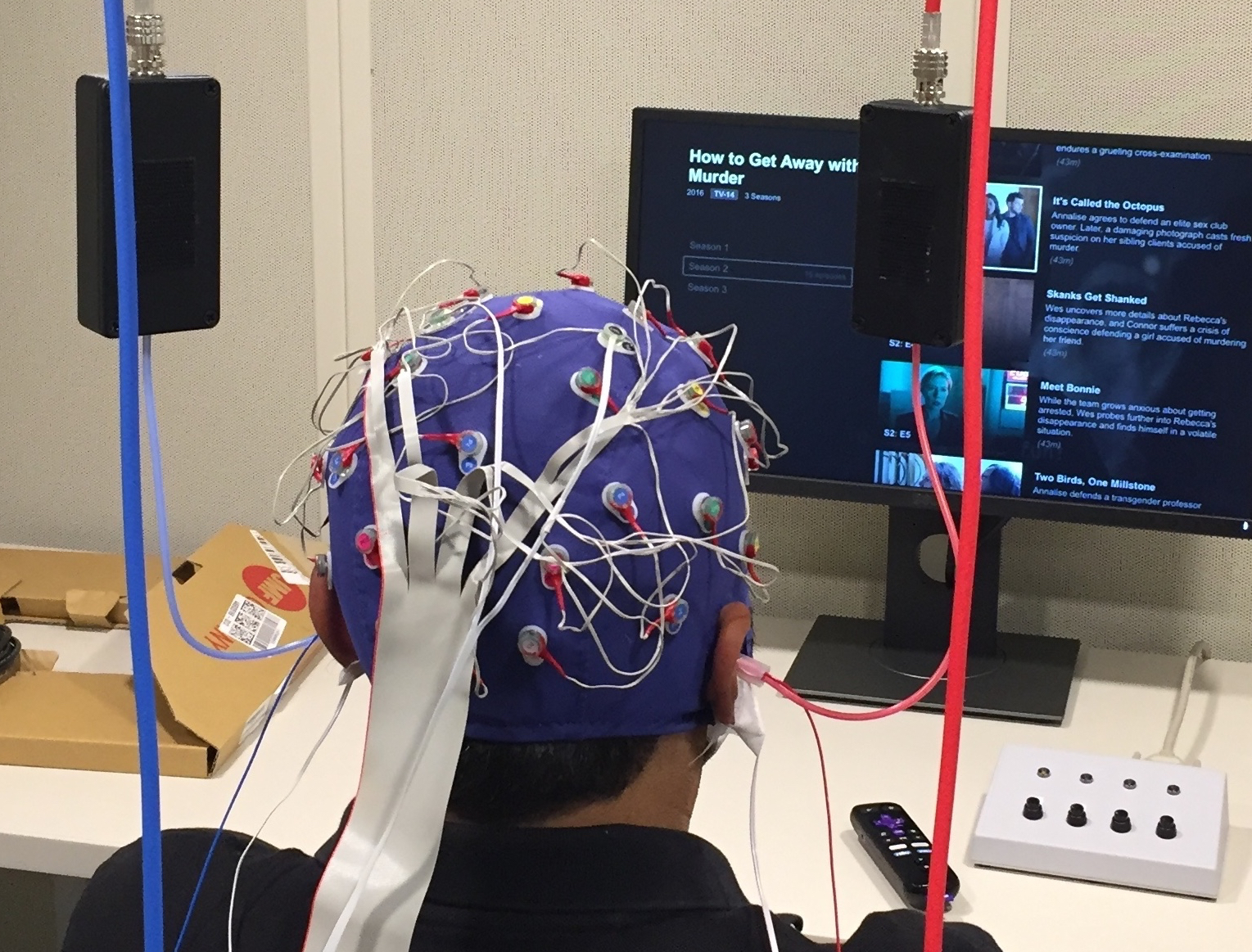

The study also takes advantage of the populations available on Purdue’s campus. Planned participants include 100 members of the Purdue All-American Marching Band, young people who have considerable exposure to loud sounds, and 40 people who are involved in the Purdue Audiology Hearing Conservation Program, an ongoing program that includes annual hearing tests for employees who are occupationally noise-exposed.

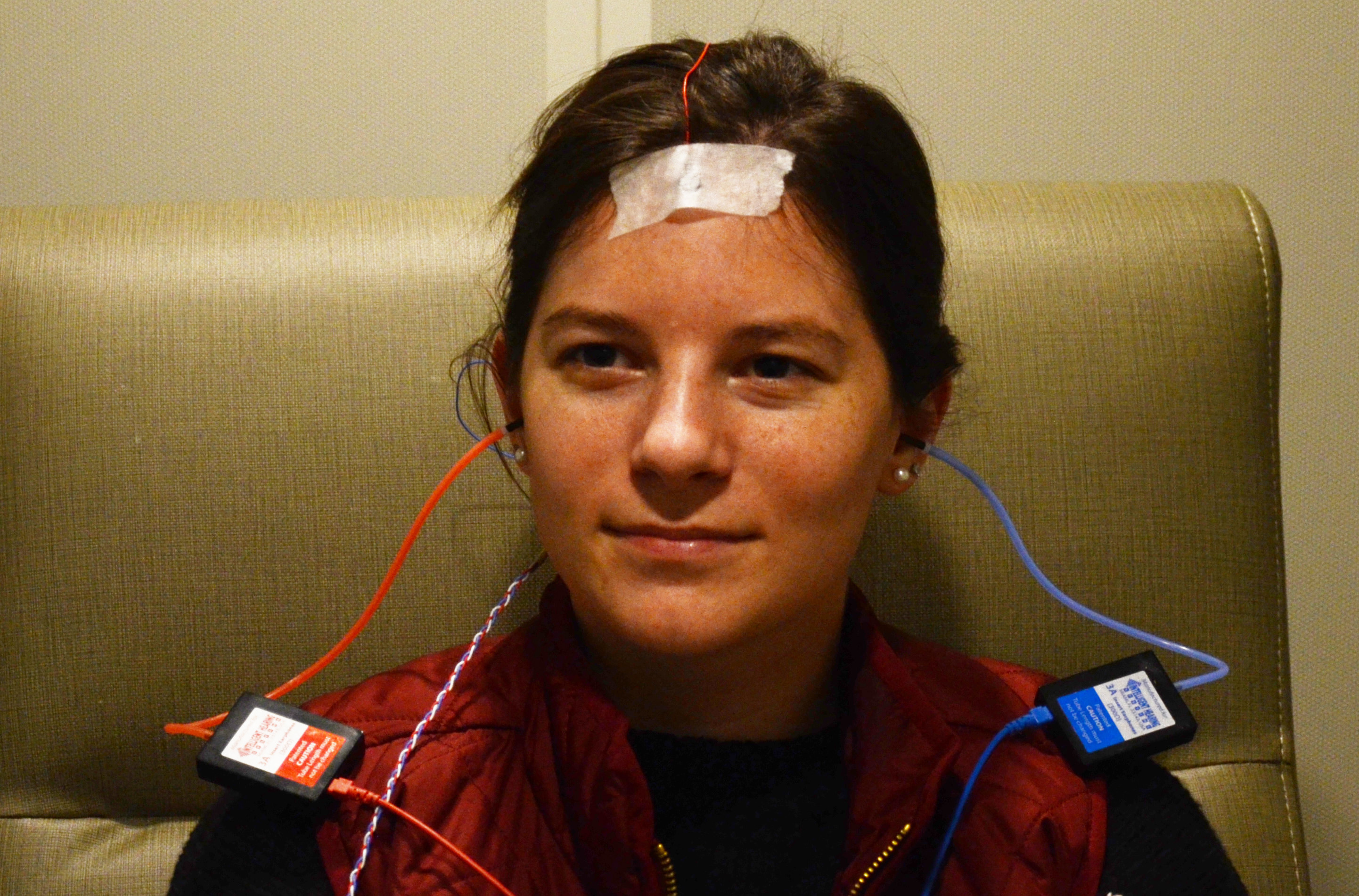

“The kinds of measurements that we are doing in the clinic as part of this study are the kinds of measurements that clinicians already know how to do, and they are already being used for other purposes in the clinic,” said Bharadwaj. But, they are making modifications and adjustments to them to see if they will pick up auditory nerve fiber damage. “The hope is if they turn out to work well, then all clinics will very quickly have these measurements available to them.”

In principal, the clinic can begin to monitor hearing with these new measures and catch hearing loss much earlier than they do now and maybe prevent more.

“If there is something damaged in your ear, knowing about it sooner rather than later would be a good idea, because maybe you can do something to stop more damage from happening, or to prevent it all together,” said Simpson. “Noise-induced hearing loss is completely preventable.”

The 5-year study will conclude in February 2022.

Grant funding is provided through: NIH National Institute of Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD)

Project title: “Individualized assays of supra-threshold hearing deficits”

Grant number: 1R01DC015989-01