Outstanding Aerospace Engineer Class of 2019: Scott Meyer

Scott Meyer was confident.

He’d spent three months practically living at Maurice J. Zucrow Laboratories and working closely with fellow Purdue graduate students Eric Wernimont and Mark Ventura on a hydrogen peroxide hybrid rocket engine, and he just knew the test fire would be successful.

In reality, he didn’t know what he didn’t know.

Meyer was a master’s student in the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and advisor Stephen Heister had pulled off the seeming miracle to secure a facility at Zucrow for the test fire. But Heister knew there probably would be hiccups.

So one day in the spring of 1992 at Zucrow Labs, Meyer waited expectantly to see an unqualified success. Initially, there were reasons to be encouraged: The ignition test produced an eruption of flame, crackling and popping, and burning fluid powering out of the back end.

Then Ventura, who was running the control panel, flipped the other switch to turn on the main flow.

“It’s kaboom,” says Meyer, exaggerating the word in an all-caps way, raising his voice and lengthening the last syllable. “We turned things off, and we’re all kind of stunned. It just obliterated the experiment.”

The concrete room was hazy when they entered — the blast shook dust loose from everything. The injector plate, which was supposed to be flat, looked like a deflated basketball, curved. The propellant lines had gotten blown out and were pointing the other direction. The chamber that held the engine had bulged larger in diameter. The VHS camcorder Meyer had borrowed from his parents to record the experiment had been blown off the stool it was sitting on. The stool was crumpled.

Heister, who’d been there to observe, finished surveying the damage and, finally, spoke up.

“Not very good rocket scientists,” he said.

Meyer starts laughing now, after delivering the final line to a story that proved to be an integral learning moment in his young aerospace engineering career.

Heister has a bit different view of his former student now: He nominated Meyer for an Outstanding Aerospace Engineer award, an honor given to AAE’s most distinguished alumni. Meyer (BSAAE ’90, MSAAE ’92) will accept the award as part of the eight-member 2019 Class on April 2.

“It is humbling and extremely gratifying to have been selected,” Meyer says.

It’s been quite a journey to this point, to be included in an elite group that comprises the top 2 percent of AAE’s alumni.

Meyer credits it all to timing, how his senior year perfectly meshed with Heister’s arrival at Purdue, how he ideally was connected with industry-to-graduate-school-transplants Ventura and Wernimont, how being employed by Arnold Engineering Development Center (AEDC) in Tennessee allowed him to work at the United States’ largest rocket test facility, how his wife OK’ed a rental home with a backyard large enough to dig a deep enough hole to conduct more hydrogen peroxide experiments, how Beal Aerospace entered the professional picture, and how he landed back at Zucrow and Purdue in 2001 — with an assist from Heister.

It was a full-circle moment.

“When I came here, I had a job for sure for two years,” Meyer says of being initially hired as senior engineer at Zucrow in January 2001, a move made possible by a $1 million grant to establish the Indiana Propulsion and Power Center of Excellence. “Beyond two years, it was going to be based upon whether we were successful at bringing in sponsored research work, which, to that point, had been struggling, in terms of experimental rocket propulsion.”

Meyer, and Zucrow, are thriving 18 years later.

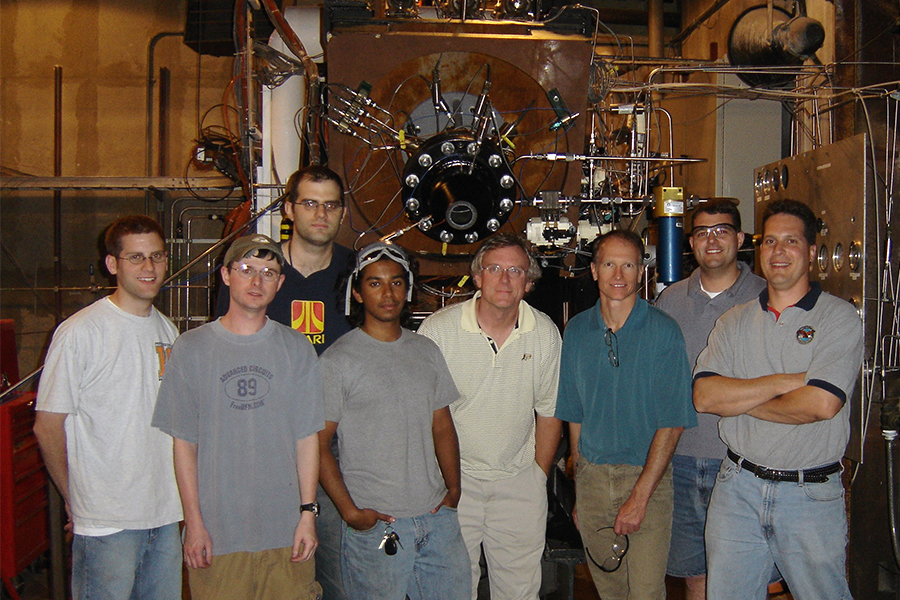

As a principal investigator then, Meyer was able to bring in contract testing from companies and hire graduate students as research assistants. He was promoted to Zucrow’s managing director in 2009 and has continued to work with faculty and students to develop unique and capable propulsion test facilities. In addition to reworking exiting facilities, he led the collaborative design activity for the new High Pressure Combustion Lab, which was constructed in 2016.

At every step, Meyer has marveled at the growth of the facility’s capabilities — and the students who use it.

“It is overwhelmingly rewarding,” Meyer says to see Zucrow expand over his tenure at the labs. “It’s really cool the talent that wants to come here. Having a very capable facility is pointless if you don’t have the human capital or talent. It’s just been pretty amazing.”

Meyer came to Purdue because he wanted to build rocket engines. He remembers seeing photos with the covered side panel off a rocket and engineers working on it and thinking, “I’m going to Purdue and doing that.”

Meyer already had some building experience when he enrolled: He built a hovercraft in high school, forcing his dad to park his truck outdoors through a couple Indiana winters while the craft was stored inside the garage, and drove it around rec fields and across puddles during his senior year.

But when Meyer started at Purdue in Fall 1986, he admittedly was overwhelmed with the coursework. It was a rude awakening to the level of effort required, he says. Most everything was highly theoretical in early engineering classes. He longed for hands-on experience. But a gas turbine propulsion course taught by John Osborne clicked.

“He made a really strong effort to connect the real-world problems and examples,” Meyer says. “He had us read technical papers and discuss them in class. That was cool. That’s when I said, ‘Propulsion is it.’ ”

Heister was added to faculty in 1990, and Meyer took a graduate rocket propulsion course from him. Meyer stayed to do his master’s work under Heister, who saw the enthusiasm Meyer had for research in rocket propulsion. As Meyer remembers, he, Wernimont, Ventura and Heister had a discussion at a local watering hole about building a rocket with elements that could only be purchased at K-Mart. That turned into the hydrogen peroxide idea, using that as the oxidizer for the rocket, and they decided to use polystyrene plastic as the fuel.

Meyer, though, had only heard about a hybrid rocket in class. He’d never been exposed to anything practical in terms of devices or anything that would be used in a lab or in a rocket.

“My timing was perfect,” he says. “I was willing to work hard to do whatever. I had some hands-on capacity. Just no knowledge whatsoever.”

That’s when the work began, as the trio of grad students scrounged tanks, valves, tubing and fittings together, using some of their own money and some that Heister kicked in, and built a test stand to fire a rocket engine.

It was an experience that served Meyer well, as he drew upon all of what he’d been taught at Purdue —the engineering fundamentals, the ability to distinguish between assumptions and facts, the ability to think critically. And it left an indelible mark.

Though the experiment attempted at Purdue wasn’t successful nor was rebuilt before he left campus, Meyer continued the work on hydrogen peroxide as a propellant on his own after college. Wernimont, who worked in Mississippi then, would drive up on weekends to Tennessee — where Meyer was working at AEDC — and they’d continue to run tests in the backyard. They wrote technical papers from that work. Ultimately, Wernimont returned to Purdue to obtain his Ph.D., and he continued the research.

When Wernimont’s path took him to Beal Aerospace, he brought on Meyer.

“I really loved what I was doing at AEDC, but at the same time, I could turn my hobby into my job,” Meyer says.

So his family moved to Texas. About three years later, Beal Aerospace closed, and Meyer got a call from Heister.

Eighteen years later, Meyer’s office at Zucrow is filled with boxes and parts needed for student projects, and he frequently has students popping in for advice. Of all Meyer has accomplished in his aerospace career, those moments may be the most special.

“The most rewarding part of my job is celebrating the achievements of our students and graduates,” Meyer says. “I am proud to be a part of the success that we have had at Purdue in providing students hands-on research opportunities in propulsion. It also remains very fun to experience tests, to see the Mach diamonds in plumes, and to feel the butterflies, in the anticipation that fire may not come out only where you expect it, when the fire button is pressed.”

More on 2019 Class of OAEs:

March 25: Julie Arndt

March 26: Chris Azzano

March 27: Doug Beal

March 28: Mike Dreessen

March 29: Tony Gingiss

April 1: Scott Meyer

April 2: Lindsay Millard

April 3: David Thompson