Outstanding Aerospace Engineer Class of 2019: Mike Dreessen

Mike Dreessen didn’t hesitate.

When his father, Carl, asked him to go for a ride in a small, two-passenger plane, Mike jumped in.

Even though he’d just watched the very first flight of the reconstructed plane fly over a South Bend cornfield, with a Federal Aviation Administration inspector watching on the ground with him, Mike had no doubts. He knew the plane intimately: He’d spent the previous three years bringing it back to life with Dad.

As a kindergartner, Mike watched Carl pull the station wagon into the family’s home in South Bend with two boxes of parts. Essentially all that was left of the Piper Cub airplane that had been destroyed in a wind storm.

Carl lugged the parts into the basement, intent on rebuilding the plane. That wouldn’t be anything new: When he was a student in Purdue’s aviation technology school in the late 1950s and early 1960s, he restored airplanes. So though it may have been a bit of an eye-opener for a young Mike — “I was, without a doubt, the only kid in the city of South Bend who had an airplane in his basement” — that moment and the ensuing three years served to nurture a love of aerospace.

Eventually, the fuselage was moved from the basement to the carport — that required remodeling inside the house because Carl missed the measurements and needed to create a bigger doorway — and was carefully protected from Indiana winters with plastic. The plane was fabric, not metal, and Mike’s pivotal role as a kid was to get up on the wing and follow the grid Dad had set: He’d take the needle Carl slipped up from the bottom, insert it into a dot and push it back down.

Mike remembers the landmark day of flight fondly, when they borrowed two wagons from his grandfather and hauled the plane out to his farm. There, Dad put the wings on and did the final prep work. The FAA inspector examined the plane, watched Carl fly it, watched Carl land it, and did a final detailed walk-around to look for any signs of damage. After the inspector signed the certificate, Carl was ready to take his first passenger.

And Mike’s life was never quite the same.

“At the time, I thought airplanes held my future. But I was also growing up in the Apollo days. Faster is better, right?” Mike Dresseen says with a laugh. “So then rockets were my thing. When I was older, I really got into model rocketry. I was building custom rockets. If one engine is good, three might be even better. So I was doing things like that where I was working on clusters and other things.

“I told anybody, by the time I was in seventh grade, that I was going to be an aerospace engineer, and I was going to Purdue where my dad went.”

Mike Dreessen made good on his pledge. He received a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical and astronautical engineering from Purdue in 1983 and has spent 35-plus years in the aerospace engineering industry.

He’ll be honored by Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics on April 2 with an Outstanding Aerospace Engineer award, presented to alumni who have distinguished themselves by demonstrating excellence in industry, academia, government service or other endeavors that reflect the value of a Purdue aerospace engineering degree.

“I feel extremely honored to be recognized by the institution that provided me with the tools and training to pursue my childhood dreams of building and flying rockets, missiles and satellites,” says Dreessen, part of an eight-member 2019 class.

Perhaps because Dreessen knew his path at such a young age and was such a gifted student, he never took a school book home to study throughout high school. His mother worked at the school, so he was there early and late and made sure to finish his homework during those periods. But high school also was simply easy for Dreessen, which meant by the time he enrolled at Purdue, he didn’t necessarily have the essential study skills.

Dreessen realized early he would need to apply himself — and that wouldn’t change throughout his four years, even when he was an upperclassman.

As a junior, a dynamics course taught by Professor John Bogdanoff had a 5:30 a.m. study session, before the class started at 7 a.m. Dreessen attended and ultimately earned an “A” in the class.

The next year, he took an orbital mechanics class under Kathleen Howell. Dreessen rose to the challenge then, too, and earned an “A,” and remembers Howell asking him, essentially, how he did it. He told her he didn’t stress or overanalyze on the final but simply applied what he learned without second-guessing.

“Coming out of Purdue, I was like, ‘After this, I can do anything,’ ” Dreessen says. “I was battle scarred from the challenges the professors were putting forward. You couldn’t breeze through it. It was battle scarred in a good way. The challenges prepared me, really, for a career.”

It’s been a career in which Dreessen has drawn on his Purdue experiences often, whether he’s worked with a team to develop and invest in the “next thing,” pushing innovation at every turn, or learned to respond well in challenging situations.

There have been plenty examples of both over an illustrious career, from soon after he graduated from Purdue and began as the assistant program manager and lead engineer for Teledyne Brown Engineering in the HEDI Test and Integration Program to his current role as executive director in Missile Defense and Space Systems Engineering for General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems Group.

More than once, he’s had to handle the difficulty of a failed test and the reality that millions of dollars and years of research went up in literal smoke.

In the early 1990s, Dreessen sat in a bunker about 1,000 yards away from a test on a new interceptor concept that had taken three years to design. It flew for 124 milliseconds and moved 10 feet before turning into a “very impressive pyrotechnics display,” he says. He could feel when it blew. Then, after it was safe to leave the bunker, he saw debris everywhere. He heard experienced members of the team calling the event a “setback,” which did not exactly match up with the word he was thinking: “Failure.” He admits it was difficult to motivate himself in the following weeks.

But it was a key learning moment in Dreessen’s career: This is what can happen when you’re trying to do things that haven’t been done before. It spurred questions and potential solutions. He learned how to conduct and lead a failure investigation. He learned how to better review designs and the types of questions that should be asked during a developmental program.

That didn’t mean every other program was a success. A setback happened again later, when a satellite made it up to orbit but lasted only two passes before communication was lost. Another happened in 2014 after five years’ worth of work for a launch that was thought to be routine, only to see another project disintegrate.

But Dreessen learned from his previous experiences and challenges — just like when he was at Purdue — and responded.

“We all knew this was hard because if it wasn’t hard, anybody could do it,” Dreessen says about the proper mindset. “This whole thing is you can’t go in assuming you’re going to be successful 100 percent of the time because you’re going to be really disappointed.

“My entire career has been working research and development programs, trying to do things that haven’t been done before. There are no wrong questions.”

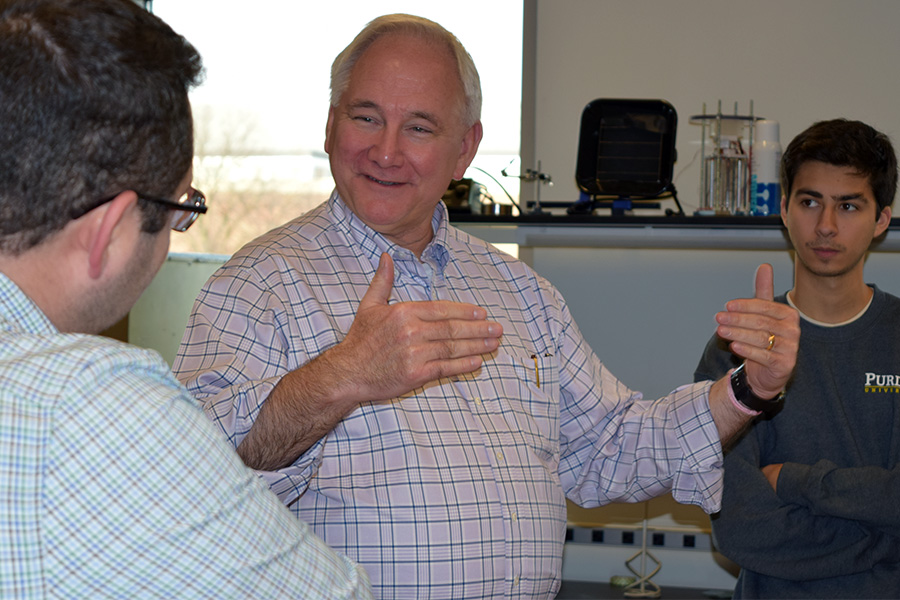

Those are the types of stories Dreessen shares with current Purdue students — and he tries to connect often. He’s a member of AAE’s Industrial Advisory Council. He comes back to campus to speak in classes and to student organizations. He’s heavily involved with AAE590’s TracSat Design Project, which GA-EMS funded.

“The most rewarding part of my career has been mentoring and influencing the next generation of engineers,” he says.

More on 2019 Class of OAEs:

March 25: Julie Arndt

March 26: Chris Azzano

March 27: Doug Beal

March 28: Mike Dreessen

March 29: Tony Gingiss

April 1: Scott Meyer

April 2: Lindsay Millard

April 3: David Thompson