Outstanding Aerospace Engineer Class of 2020: Yen Matsutomi

No fear.

No hesitation.

No misplaced attention.

No day-dreaming.

Yen Matsutomi always has been brave, a risk-taker without realization. With every ounce of her being, she dives in, with unwavering focus on moving forward.

Her upbringing cultivated traits that ultimately prepared her to rise to meet challenges and achieve incredible success. It’s never been so much about the end game, just one step, then the next. One challenge met, then tackle the next.

She simply knew what needed to be accomplished and did it, without fear of the unknown, with a tenacity to seize moments.

Bill Anderson called it “courageous,” how Matsutomi adapted so well to each new situation that arose in her life, many that would strike fear in others.

As an elementary-school-aged kid, she was sent from Taiwan to Singapore to learn English, by herself, forced to stay with a host family. She thought it was only going to be for a summer, three months max. It was years, through the equivalent of high school.

“I just had to make it work,” she said. “It kind of trained you, to dump you in a new environment and you figure it out.”

That fearlessness proved useful again when she returned to Taiwan after that period, on her own again, by choice this time. She knew she wanted to go to the U.S. to study aerospace engineering, so she took odd jobs to support herself, proving to herself she could live and operate on her own.

That risk-averse nature was necessary again when she came to the United States to attend Purdue University, navigating through literal new territory and the Midwest. She started fresh again only a year later, spending a year abroad in England.

All of it kept her focused on moving forward. She never spent a lot of time planning or over-analyzing. That was probably good, she knows now: Too much thinking about each small step along the way may have prevented all of the giant leaps.

Instead, she called on the resolve she’d built again and again.

To combat complex challenges while pursuing master’s and doctoral degrees in the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

To overcome intensive projects at Blue Origin, first as an engineer and now in an executive leadership role.

At every turn, with every task, in every role, Matsutomi displayed laser-like focus in the pursuit of excellence — and delivered. More than delivered, she has excelled.

And those moments of overcoming, of achievement, of success brought her here: Awarded the highest honor bestowed upon AAE alumni, as an Outstanding Aerospace Engineer.

“It never crossed my mind that I would one day get an OAE award,” Matsutomi (BSAAE ’03, MSAAE ’05, PhD AAE ’09) said. “I remember sitting in the OAE banquet when I was a Purdue student, admiring in awe at the achievements that the awardees have accomplished. Being selected as an OAE means a great deal to me and is deeply humbling.”

Matsutomi and eight other alumni will be honored on April 12 in a virtual ceremony.

Maybe then she’ll take time to reflect on how her upbringing perfectly crafted her to reach such heights.

Finding Purdue

They were beautiful.

The vivid greens. The vibrant red streaks. The sparkling traces falling to the ground. The booms that sent reverberations through the system, shuddering from head to toe.

A young Yen Yu would sit in awe, watching fireworks paint the sky on Chinese New Year. Her family would shoot off their own, too, and Yu was enamored with the spark, the fire, the sound, the result.

Growing up in Asia, she said she was sheltered from public media exposure to Americans’ feats in space, the fascination with astronauts and the country’s persistent pursuit of space exploration. It all sounded so far from reality.

But the desire to see fire in action, to send things flying, that was real and tangible. And it resonated.

As she got older and gravitated toward math, science and physics, she saw the broader picture. Aerospace engineering ideally could align interests to not just see that next big fire, hear that next loud boom but also understand why it happened and to influence it.

A search through a book of top U.S. universities told her Purdue University was one of the best destinations to learn more. She applied to three universities, Purdue, University of Michigan and Georgia Tech, and was accepted to them all. She picked Purdue because “this one has a lot of astronauts, something must be great about this school.”

She had never stepped foot in the United States.

Culture shock was real that first year in Indiana. And it was real again, in a different way, when she spent her second year in college studying abroad at the University of Bristol in England. And the shock, in a different way, was real in Year 3 when she returned to Purdue and got a call from a professor asking her about graduation. She hadn’t even realized she’d had a bunch of credits coming in from testing out of classes, and she already was ready to receive her bachelor’s degree.

But what about her career path? Her life? She hadn’t found “it” yet.

Finally, in her last semester of undergrad, it was revealed in the form of a rocket propulsion course.

“This is the topic I came here for,” she realized.

She had to stay.

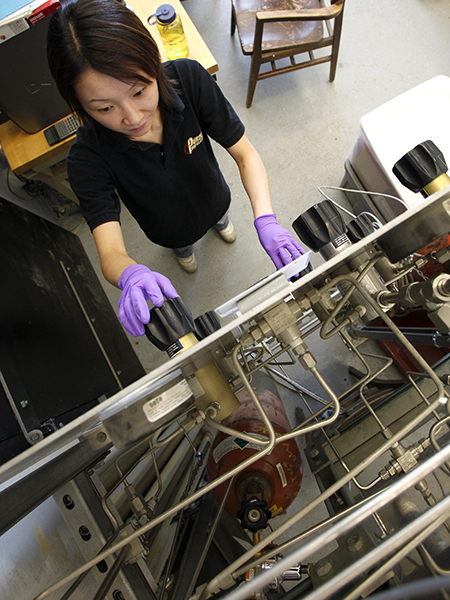

And then she stumbled across Maurice J. Zucrow Laboratories, and she knew it’d be a while before she would leave again.

“You see what we call the fire model combustion in the lab, and that was cool. You hear the sound. You see the fire. You feel the vibration. It never quite sunk in (before),” Matsutomi said. “There are a lot of times I hear people, for example younger engineers or my peers, who say, ‘Oh, I’m passionate about space. I knew all along I wanted to be in space.’ I always envy that. It was never like that for me. I just enjoyed every step along the way, but I was never like, ‘Oh, that is exactly what I want to do.’”

Bill Anderson knew what he wanted: Yen Yu in his research group.

Despite limited interactions with her as an undergrad, he was impressed. Based off responses to an oral make-up exam he’d given her, he knew she was wicked smart, great at math and analytical. But he wanted her to try something new in graduate school: Experiments.

“She said yes to everything,” he said with a smile.

Even if she didn’t understand the scope of what she was being asked to tackle.

It wasn’t until she was a master’s student in AAE that she learned combustion instability was something every engine experiences, and she doesn’t remember anyone telling her then it was one of the most complex problems in engineering.

When Anderson suggested Yu compile benchmark data for combustion instability for her Ph.D. work, she did what she always did: Said yes, with enthusiasm, and dove head-first into the challenge.

By the time Yu completed her thesis on the topic about four years later, she honestly was just happy she was finished. By that point, she’d already been telling the joke that Ph.D. stood for “permanent head damage.”

But Anderson knew then how substantial the research was. Not only has the experiment been used as a benchmark across the world since it was published, it also begat innovation at Maurice J. Zucrow Laboratories, where Yen Yu spent long days during graduate school.

“It was such a landmark experiment for entire propulsion (department) for Purdue,” Anderson said. “You would never know talking to her. She is extremely modest about her accomplishments.”

That’s still the case.

When asked about her experiences in AAE and at Zucrow, Yen — who married Yu Matsutomi in 2009 — didn’t even mention the impact of her experiment. Only when pressed about the reality of the influence did she laugh and relent, almost sheepishly admitting to its significance.

“I guess I never anticipated it’d go that far,” she said. “It was like, ‘If we think of a way to make an experiment that could collect so much more data by automating the boundary condition, we could generate so much data that people could model.’ I was like, ‘OK, that sounds really awesome. Let me think about how to make that happen.’

“I was focusing on execution a lot more than focusing on the impact, at that stage. Blindly put, I think I wasn’t smart enough to see the overall impact, the bigger picture, at that time. I was given a task, a vision, and I was just focused on executing it.”

That kind of determination continued to define Yen Matsutomi’s career, if not her life.

Rising at Blue Origin

During each step of Yen Matsutomi’s meteoric rise at Blue Origin — which wanted her so badly, the company actually applied for a green card for her, an action not repeated since for an international student — an unrelenting mentality to always do the best work, no matter the circumstance, has been on display.

When she started as a development engineer, she set up hardware. She went in each day thinking, “To be the best engineer, I need to understand what the hardware does, how it impacts the system, how it is set up to interface with components.”

When she analyzed or characterized the component, she wanted to know more than anyone else.

When she set up test data reduction code, she wanted to reduce cycle time and make it easier for other people to use.

When she was the test engineer testing the assembly, she needed the technical curiosity to know what the system does and how it interacts with other components, such as test facility, instrumentations and test data acquisition system, developing the ability to answer any question.

When she started leading a group, she worked to be the best leader, not only in technical knowledge but by making sure she was someone who would listen, who would do the right thing.

The drive won’t leave, not now that she’s found what she loves to do, even if she never envisioned it as her destiny as a kid.

“It was exciting, I would say, incrementally,” she said. “I got to industry where we started making bigger fire, hearing louder sounds, feeling a bigger rumble. It materialized into, ‘Oh, the parts that I develop are flying.’ Flew, landed. Let’s do it again. Now, we’re making an even bigger engine, bigger fire, a bigger rumble and see the rocket land. The focus now is on building excellent teams that operate efficiently. That’s how it comes, incrementally moving to what’s next, what’s next, what’s next.

“I happened to stumble onto this path, and it makes me love it more and more every day.”

Even despite the challenges.

And there were plenty in Matsutomi’s first five years at Blue Origin, spent working on the BE-3 engine for the company’s New Shepard vehicle. She was involved from prototyping subscale to full-scale component testing to full-scale engine testing to development at qualification until it flew and landed.

Zucrow ideally prepared her for that work with its unique hands-on experience — “a jump start,” she called it — and she quickly established herself as a more-than-capable engineer in all phases, whether it be doing her own analytical design, operating a lab herself or putting hardware together.

Everything she’d already done at Purdue.

“What’s unique about Zucrow is the students do it all, with the guidance of senior graduate students or engineering faculty and staff. But they don’t do it for you. They oversee and make sure you have all the safety protocol in place, all the engineering sets are reviewed,” she said. “That kind of experience equips you with skills that once I got to Blue, I no longer needed additional training or coaching — what sometimes people would call on-the-job training before I get started.

“Purdue gave me all the tools and knowledge I need to be successful. I couldn’t do my current job well without all those foundations in place.”

Those five years on that engine were her career highlight, she said. But also “bittersweet” because of how difficult the project was.

Combustion chamber instability wasn’t surprising, nor was it surprising to encounter hardware failure during rocket engine development, she said. Typically, it’s about compromising for the optimal engineering solutions, thermal compatibility, structural compliance, engine performance, as well as engine stability, she said. When one problem was solved, they simply had another waiting.

When New Shepard launched and landed for the first time, she cried, overjoyed at seeing something that she was so heavily involved in and exerted so much energy on succeed. Her work on the engine was a key contributor to New Shepard winning the Collier Trophy in 2016, the award given for the greatest achievement in aeronautics and astronautics in America each year by the National Aeronautic Association.

“It was highly stressful,” Matsutomi said of those first five years, “but seeing it work in the end and it all coming together was definitely rewarding.”

After multiple New Shepard missions in 2015, Matsutomi transitioned to a lead role establishing technical standards, improving processes, and advancing analysts tools for injector and combustor development across all Blue engines.

In 2019, she was named senior director of the Engines Design Office that supports all Blue Engines programs. She’s responsible for all Blue Engines engineering skills in design, development and test from engine components to the integrated systems and technical process definition from concept through flight. She leads an organization with more than 350 employees.

Which presents its own new daily challenges.

The first five years were spent as an independent contributor, focusing on making a product work. Success could be defined on whether the product worked as it met the requirements, demonstrated performance and demonstrated it was stable to use and reliable. There were measurables to say, “I did that successfully.” In a technical management role, the focus is on establishing the engineering process to be more robust and to minimize errors, building teams that deliver successes.

“I strive to enable the team to operate efficiently and effectively, giving them the tools they need, giving them the process they need to accelerate the development cycle,” she said. “So when things work well, all the glory goes to the individual who made that product work. When things don’t work, you have to be there to own the problems and the fixes … so it is harder to quantify satisfaction.”

Matsutomi admits she misses the technical work, laughing that “life was much simpler back then.” The shift to a leadership role just meant she’s had to adjust again, which certainly isn’t new.

“I wasn’t one of those people who plan for their career development very well, but I enjoy every step of the way,” she said. “As long as you enjoy what you do and strive for the best and enjoy the ride, I would say I’m still pretty happy at who I turned out to be.”

More on 2020 class of OAEs:

March 29: Doug Adams

March 30: Chris Clark

March 31: Darin DiTommaso

April 1: Doug Joyce

April 5: Loral O'Hara

April 6: David Schmidt

April 7: Stevan Slijepcevic

April 8: Rhonda Walthall