The landing spot: Neil Armstrong statue one of top destinations on Purdue's campus

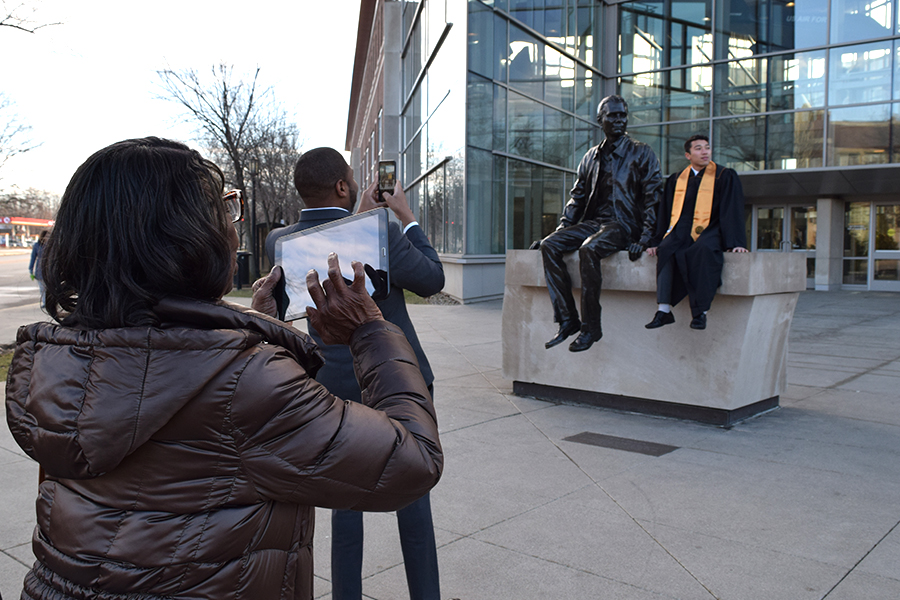

Akira Isaac stood up straight, pulled his shoulders back, and smiled widely.

Click, one photo down.

Then he grabbed the edge of the ledge, bounced up effortlessly, plopped onto the plinth of cold limestone and stared off in the distance, looking toward the sky, mimicking Neil Armstrong next to him.

Click, another photo.

Isaac donned a couple more poses before he walked away, acting-photographer father and grandparents in tow, the task done.

Then it was on to the next student. And the next. And the next. And the next.

As has become routine on Purdue University Commencement, students, along with families and friends, recently lined up along Stadium Ave. All eagerly awaited a chance to snap photos at what has become one of the top destinations on campus: The Neil Armstrong statue in front of the building that bears his name.

For Isaac, there was never a doubt he’d be in cap and gown perched near the statue in front of Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering on graduation day.

“One of the most symbolic things when it comes to going to Purdue University, especially if you’re studying aerospace engineering, is the fact that Neil Armstrong graduated from Purdue,” says Isaac, who earned his bachelor’s degree from Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics in mid-December, 63 years after Armstrong received his bachelor’s in aeronautical engineering.

“It’s been something you always look up to, especially me. So being able to take a picture with the statue of Neil Armstrong means a lot to me for my passion in space exploration.”

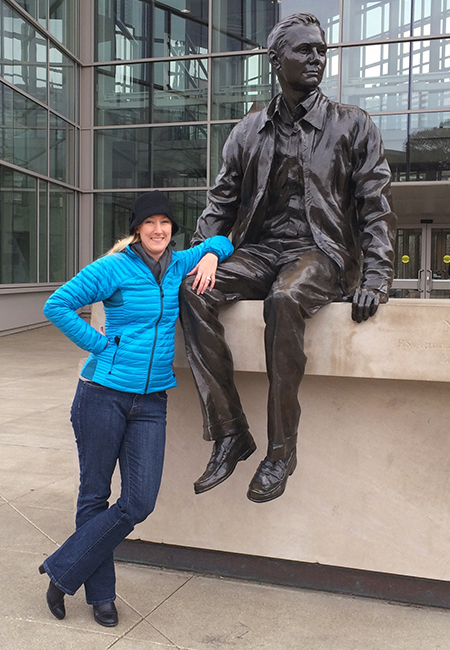

But it’s not just one special occasion that draws people to the statue. And it’s not only aerospace engineers who capture the moments.

The statue is a frequent stop for alumni — regardless of degree — when they return to campus.

The statue is a sought-out destination for visitors to campus, too. On an overcast day over winter break, a group of four people stopped, hopped and posed, hardly another soul around. Days later, Iowa basketball fans strolled into Neil Armstrong Hall before their school played Purdue in men’s basketball, and when one in the group saw the statue, he said, “It’s Neil!” Then, naturally, they had to snap a photo.

The statue is the meeting place at the end of Purdue Space Day, the annual event that hosts hundreds of children from third to eighth grade, for kids to get group photos with the event’s featured guest (an astronaut) and with Armstrong.

And, often, TV broadcasts of Purdue athletic events head into or come out of commercial breaks with a well-lit shot of Armstrong glistening in the Moonlight.

The Armstrong statue has become the ultimate landing spot. If possible, it could be even more popular in 2019: July will be the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission that included Armstrong becoming the first human to step foot on the lunar surface.

And it’s all more than Chas Fagan could have hoped.

Fagan, a nationally renowned artist, was selected to create the statue more than a decade ago. Though in every project he tries to think ahead to the impact it could have — “If I were a visitor, what would I want? What would be cool?” — he called the response to this particular project “amazing.” When told lines form at Purdue Commencement for students to capture their special moment with the statue, Fagan says it left him humbled.

But he’s not necessarily surprised at the statue’s popularity.

“I envisioned people hanging out. It’d be a place to meet people. It’d be a place to have your lunch or study, in the sun, because the stone is warm. I just thought it’d be a great spot,” Fagan says. “Within a short time, I was told that was happening, so once that happened, I thought, ‘This is great. Mission accomplished.’

“But beyond that, where he’s become this wonderful icon, that’s his doing. Statues kind of take on a life of their own, and he has.”

A look back

When Fagan first learned in 2006 that Purdue planned to commission a statue to honor Armstrong, he quickly brainstormed ideas of what the piece could be.

How could he not push hard to be awarded the project?

“One of my first memories in my life was a moment of serious commotion in my house, being picked up and plunked in front of the TV and watching that grainy video,” Fagan says of the 1969 Moon landing. “I was one of those little kids fascinated by what was happening on TV and knowing that there were Americans on the Moon. So I’ve always been a fan of Neil Armstrong.”

Fagan’s concept for the statue, though, was not to feature Armstrong as an iconic astronaut, adorned in a NASA suit with moon boots, unabashedly celebrating one of the country’s greatest achievements. Instead, Fagan wanted to showcase Armstrong as an undergraduate Purdue student in the 1950s, complete with penny loafers, windbreaker, books and slide rule. Fagan wanted students to be able to relate to Armstrong, not be intimidated.

Fagan’s proposal to Purdue included paintings of what the piece could look like and, based on architectural designs of the new 210,000-square-foot engineering building, where he’d place the statue. He also offered a unique feature in the lawn around Kirk Plaza: Concrete imprints of moon boots trailing away from the plinth, spaced apart to replicate bounding steps in microgravity on the lunar surface.

“I think the message it gives is just wonderful that you can walk in his footsteps as he did or that he’s looking away, looking at his future footsteps,” Fagan says. “It has all the right storytelling ability.”

The pitch touched all the right notes, and Fagan was granted the commission.

“The first instant is absolute joy, and the next moment is, ‘Oh my gosh, I need to come up with something good,’” Fagan says, laughing, recalling the moment.

It took about a year to complete the bronze sculpture, an 8-foot-tall, 125-percent-scale likeness of Armstrong.

And there certainly were challenges along the way. But even those produced memorable moments.

That idea for the moon boots? Someone from Purdue asked Fagan how he was going to reproduce them. Fagan said he’d have to study a photograph, make a copy, sculpt it, and then make it in stone. That response wasn’t received with much enthusiasm, Fagan says now laughing, but then someone piped up and asked, “Why don’t you use a real moon boot?”

“I quickly realized, there’s normal, and then there’s Purdue,” Fagan says. “The thought is, ‘Well, why not just shoot for the Moon?’ I had nothing to do with it, but it was all arranged for me by Purdue to go to a government storage facility and take a mold off a real moon boot.”

Another potential issue was how high to make the base, made of limestone from Indiana. Fagan made a hard pitch for a specific height of the plinth.

“Trying to make it seem high and tall without being unreachable so if you really wanted to get up there, you could. But not so high that it’s so dangerous,” he says. “There’s this happy medium that we made because my goal was to have students hop up and join him seated there on the stone.”

Armstrong heard Fagan was looking for photos of him as a younger man so Fagan could make a model closer to what Armstrong looked like in college and garner insight into what kind of notebooks and tools he may have carried. Fagan didn’t personally share that, though. Still, one day “out of the blue,” Fagan says, a FedEx box arrived at Fagan’s house. After opening the box, Fagan saw the top filled with photographs, of Armstrong as a boy, as a teenager. Fagan noticed the corners on some of the photos still had little black adhesives, like they were pulled out of an album. At the bottom of the box were notebooks, including a spiral one that had a logo embossed on it with the school’s mascot.

“I thought, ‘This is just perfect.’ Then I pull it out and look at it, and it’s got his name on it,” Fagan says. “It’s his physics notebook. Oh my gosh. I quickly just photographed everything, every angle, put it right back in the box and sent it right back. There’s no way that archival, valuable treasure would hang out in my studio.

“That was a very generous thing to do.”

The biggest challenge, though, was actually one of Armstrong’s features. Fagan had viewed a lot of photos from NASA and, even, some of Armstrong’s childhood photos, to try to get a firm handle on Armstrong’s profile. But none of the pictures gave him a good enough idea to model.

Eventually, Fagan asked Armstrong for help.

Armstrong agreed to meet in Washington D.C., while he was in town for a conference. They met in a windowless little dining room at a large hotel, Fagan remembers.

“It was just absolutely a dream come true for me,” Fagan says. “He was really generous with his time.”

Fagan eventually did spill to Armstrong his Moon-landing-moment story, watching on the TV when he was a kid, but it was only because Armstrong’s inviting personality allowed Fagan to feel so comfortable around his boyhood hero.

Fagan saw Armstrong again, on Oct. 27, 2007, when Armstrong attended the dedication of the Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering, the day after the statue was unveiled. Fagan was seated in front of the statue, a vantage point that allowed him to see Armstrong’s first reaction. When Armstrong came out of the building and around the corner to where the statue was, he paused, took a breath, touched it, smirked and moved on, Fagan says.

“It was great,” says Fagan, laughing.

After the building dedication, after Armstrong spoke, after the celebration with a group of astronauts, the crowd dispersed, Fagan with it.

Fagan had forgotten one thing: To take a photo with the statue.

Fortunately, he has seen plenty of others.

Friends who are Purdue graduates and others who have taken prospective Boilermakers on visits send Fagan photographs of the statue. He’s seen others on social media, too, including one of his favorites. The photo depicts a young woman, in cap and gown, standing on the stone so she could be right next to Armstrong … to give him a kiss.

“A life of his own indeed,” Fagan says. "It’s just amazing."

As part of #MoonLandingMonday, a social media campaign celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, AAE will post submissions of students, faculty, alumni, and visitors posing with the Armstrong statue. Email photos to aae@purdue.edu, and please provide a name and connection to Purdue. Photos will be shared in a gallery here, as well as potentially on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook.