Alumnus helps develop aviation radio simulator for new pilots

Muharrem Mane didn’t even try.

While working to earn his pilot’s license, Mane avoided taking solo flights into Class C airspace near Indianapolis airport, the largest one near Lafayette, Ind., where he was a student at Purdue. One thing was holding him back: Flying there would mean Mane would have to speak on the radio with air traffic control. And he simply wasn’t comfortable with that, not confident in having the right phraseology, speaking at the correct speed or being able to repeat back clearances correctly.

He wasn’t alone then — and still isn’t.

Though aviation schools and flight instructor training are helpful in teaching technical details of learning how to fly, there often is a lack of hands-on, in-flight experience of acquiring radio communication skills.

So Mane and his business partner, Eren Hadimioglu, are working to solve the problem.

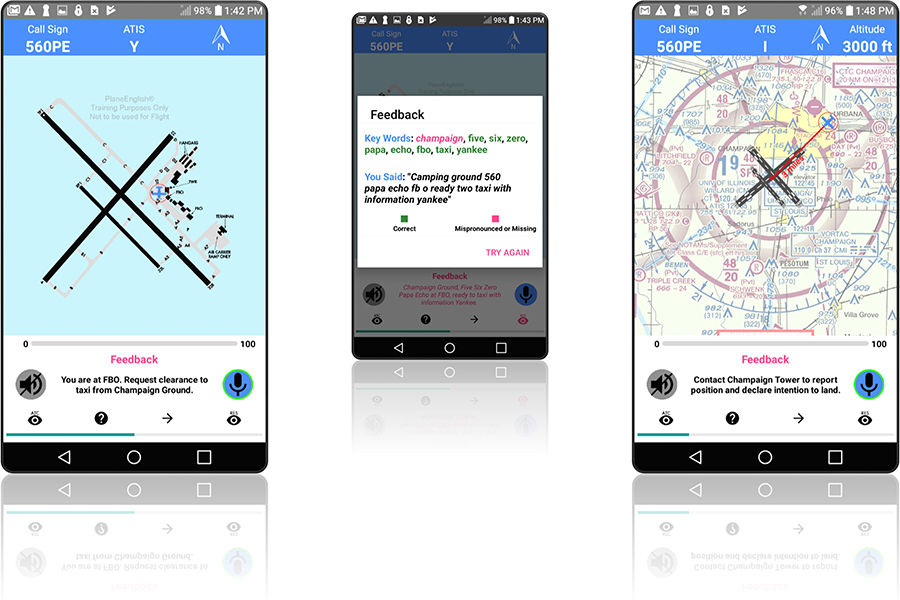

The Purdue graduates created and developed PlaneEnglish, an aviation radio simulator to help new pilots acquire and master radio communication skills by becoming proficient in aviation phraseology and communication, developing advanced skills in realistic environments, giving instantaneous feedback through voice recognition and speech analysis, and reaching Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) English language standards.

They started the company in August 2017, and they’re pushing to get the product into the hands of students and flight training programs. The app-based tool currently is available for Android — there’s a 14-day free trial on Google Play right now — and the next step is developing PlaneEnglish for iOS. A Kickstarter campaign has been launched to help toward that goal.

“There is nothing out there that we have found that is as easy, accessible, and effective at the prices we’re thinking of charging for this,” says Mane, who has bachelor’s, master’s and Ph.D. degrees from Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics. “It’s combination of ease of access — train on the go — the way we’re doing the speech analysis, and feedback to the user that is something that doesn’t exist out there.

“We’ve gotten feedback that this is something very different and very new in the area of flight training.”

One way students currently are trained is in a classroom environment in ground school in which a teacher relays what is supposed to be said, and students practice with other students. There are companies that provide exposure to radio communication, too, via the internet, in which pilots flying on a simulator can speak with air traffic controllers. CDs and transcripts of specific dialogue and responses also are available as tools. But Mane says none of those options is in a realistic environment.

And the one that would be realistic — learning while actually flying — actually isn’t particularly suitable either.

When prospective pilots first start lessons with flight instructors, Mane says it’s not uncommon for the flight instructors to let the pilots handle the controls and the throttle — to, essentially, fly the plane on their own — but rarely allow them to interact with air traffic control on the radio.

On one of his first flights with an instructor, Mane remembers being told what to say and practicing it aloud before pressing the button to start speaking with air traffic control. By the time he pushed the button, Mane had forgotten half of what he was supposed to say, then repeated it. But speed and clarity is especially important during landing — considering there could be more than one airplane trying to land at roughly the same time — so the instructor pushed his own mic to talk to the tower. Mane says he was “either too slow or I messed something up and there was another airplane close by, and the instructor didn’t have time for me to get my sentence right and clutter the airwaves.”

“If you only practice a handful of times, you just don’t get good at it,” Mane says.

PlaneEnglish has more than 50 lessons accessible at any time. Lessons guide users through simple and complicated interactions with air traffic control on every phase of flight from taxi out, to takeoff, to airspace entrance, to approaches, to taxi in. Each simulation includes visual clues that show altitude, distance from an airport, and direction. A variety of airports can be selected or one will be randomly selected for the user.

Users are required to respond properly in specific situations, using the correct phraseology, speech rate and other factors. There can be as many as five or six exchanges back and forth with “air traffic control.” Then users are graded on those responses.

“Every time you do a lesson, there is going to be something that changes,” Mane says, “so you can’t just memorize.”

In conversations with flight schools, especially those that train international students, Mane says schools are seeing the utility of PlaneEnglish by giving it to students even before they join flight programs. It’s a means of practicing speaking English, which is a requirement for pilots worldwide, even before they come to the United States to start flying. It can reduce pre-flight preparation for students, Mane says.

ICAO has a grading system for assessing English language proficiency in certified airmen that includes six levels. ICAO Level 4 is required to fly airplanes in international air traffic and to use English for radio telephony purposes. In July 2017, the FAA introduced something similar with its Aviation English Language Standard (AELS), which requires that holders of an FAA certificate or rating should be able to communicate in English in a discernible and understandable manner with air traffic control, pilots, and others involved in preparing the aircraft for flight and operating an aircraft in flight. The FAA advisory said, “this may or may not involve the radio.” Actual standards on how to assess a pilots proficiency do not exist, Mane says.

He’s hoping PlaneEnglish can help create a baseline.

“The FAA, in the last two years, has come up with advisory circulars about how students or pilots could be assessed and has provided guidelines on how to determine if a pilot meets the FAA AELS,” Mane says. “The FAA is starting to ask instructors to try and test their students about their English speaking and their ability to communicate on the radio. Instructors aren’t equipped to do this. They’re not trained. They don’t have a basis for how to do this. So we see that as another area of utility for what we’ve created.

“If everybody were to use PlaneEnglish, they’d be training to the same standard and be graded by the same standard, so you’d have this standardized way of talking on the radio and would be able to reduce idle talk or lengthy communications that can be a problem sometimes and, above all, be safe.”