Purdue student project to add flare - via 100-foot flamethrower - to Burning Man event

Burning Man is every bit a spectacle.

The weeklong event is hosted in the desert, within a pop-up “city” constructed by its visitors, with the purpose of cultivating a community of creative thinkers who celebrate artistic self-expression and provide experiences in “grand, awe-inspiring and joyful ways that lift the human spirit, address social problems and inspire a sense of culture, community and personal engagement.”

So a 100-foot flamethrower attached to a fire truck called "Heathen" certainly will belong.

That’s exactly what a group of students in Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics was tasked to provide for this year’s event, which opens Aug. 26.

The “Big Friendly Flame” was one project in AAE 53500, Propulsion Design, Build, Test, in Spring 2018 with the intent to develop, assemble, integrate and test a large, artistic flame device. The 10-member team delivered the project to Walter Productions, the company that sponsored the project, in July. Some members of Purdue’s team headed out to Burning Man in the Black Rock Desert in Nevada midweek to help to get the project integrated.

By the end of the week, it’ll be center stage.

“I was interested in doing a Burning Man project because most of the work we do is very targeted, very focused on some specific research objective. We want to learn some specific thing,” said Carson Slabaugh, an AAE assistant professor who taught the course for the first time in the spring. “As an engineer, I really enjoyed the opportunity to design and build something just for the fun of doing it.”

It’s not the first time the course has designed projects to be displayed at Burning Man.

In 2015, a student group designed a “pulse jet,” twin valveless pulse jet engines that attached to Walter’s “Mona Lisa.” In 2014, another student team designed “Helios,” music-controlled propane torches that initially were attached to Walter’s three-story mobile dance party machine. In 2013, a team of students created a “combustible vortex ring generator” to be mounted onto Heathen. That device was featured in a piece on “Discovery Channel.” Those classes all were led by Timothée Pourpoint, an associate professor in AAE.

Prof. William Anderson was the initial point of contact with Walter Productions and its founder Kirk Strawn, and Anderson facilitated the connection with Slabaugh for this year’s project.

The directives for this year’s project were general, in a way – “They wanted a really, really big flame,” Slabaugh said – but there were restrictions. For one, the team would not be allowed to use liquid fuel.

“Liquid fuels are much more dense than gaseous fuels and, therefore, carry a lot of momentum when they are ejected into the air. Unfortunately, any fuel that is ejected but doesn’t burn comes back down, so you have to maintain a safety perimeter. That just isn’t possible at a festival like Burning Man where this flame effect is going to be mounted on a truck and driving through crowds of people,” Slabaugh said. “So we had to use propane, which is a gas at atmospheric conditions. That makes it really, really hard, actually, to get very large-scale flames like this. Liquid fuel flamethrowers can reach distances of 40-60 feet, but we were stuck with a gaseous fuel and needed to reach flame heights that are twice as large as known liquid systems. That was the technical challenge.”

Ultimately, it produced a bit of a backward course, Slabaugh said. Typically, AAE 53500 follows a traditional aerospace design sequence with concept development and preliminary and detailed design reviews before, finally, a build. But after evaluating how difficult it would be to analyze the Walter Productions project because of uncertainty in models, among other things, the adjustment was made to build a prototype first.

That’s where Maurice J. Zucrow Laboratories showcased its value, again.

The nation’s largest university propulsion lab allowed the team to grab pieces off the shelf from previous experiments to build a prototype that could have cost as much as $90,000 if not for Zucrow’s resources.

“It helped that Zucrow has all these parts and components laying around from previous years, so it was kind of like why not go at it and do it, essentially, for free at first to make sure the concept works?” said Philip Piper, the team leader on the project and a graduate research assistant under Pourpoint. “(Zucrow is) amazing because they really have all the expertise, all the components, all the facilities that are needed.”

Initially, the team started with a typical gaseous ejection process, effectively like having a flamethrower hooked up to a propane grill cylinder, and lighting it off. Pushing that system to its limits only produced a 12-foot flame height. To reach greater heights using a gas-only system would be an “expensive endeavor,” Piper said. So that was ruled out.

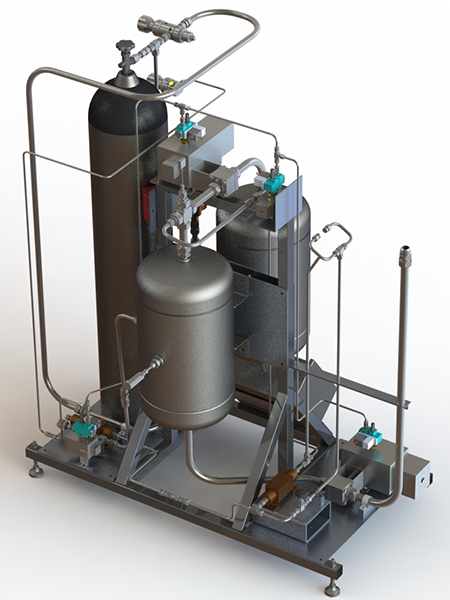

The system that ultimately was created has three combustion devices: A pilot system that stays lit at all times; a torch ignitor; and an ejector. The team also built an “accumulator,” or a tanking system, to transfer liquid propane into it and eject the propane as liquid. It flashes to vapor quickly. But using an accumulator system as well as ejecting the liquid allowed the team to bring the pressure to about 500 PSI. A typical propane tank has pressure about 100-150 PSI.

“We created a nitrogen pressurization system that let us not only eject the propane in a liquid phase but also push it up to much higher pressures,” Slabaugh said.

Testing showed the larger amount of propane mass ejected increased the flame height.

A liquid propane test in March with 480 PSI and 16.4 pounds of mass flow produced a 103-foot flame height – as well as a vortex ring and massive, lingering smoke ring. Ultimately, Slabaugh said the team reached nearly 130 feet in testing. The device delivered to Walter Productions, which cost about $16,000, will reach 100, but a couple modifications could allow it to go higher, Piper said.

But at 100, there still is plenty of awe factor.

“That’s kind of a cool part: You see it, but you also feel it, you hear it,” Piper said. “It’s kind of a full experience.”

Piper was joined on the project by Dr. Rohan Gejji, a post-doctoral research associate in Slabaugh’s research group, as project mentor, as well as AAE students Hasan Celebi, Blair Francis, Tristan Hagerman, Mark Hurt, Naveen Joel, Steven Pugia, Angel Rodriguez and Brandon Smail.

Piper attended Burning Man last year and is eager to see his work on display when he attends again this week. Especially because it’ll be mounted on the Heathen, which carries 600 pounds of propane. That amount of propane will produce about 20 fires from the flamethrower, though the Walter Productions team also could decide to pulse the flame to the beat of music via a remote control.

The variety of options just goes along with the event, one that Piper described as “crazy” and “controlled chaos.”

“There’s people everywhere at every hour of the day,” Piper said. “It’s a city that is sprung up out of nowhere. It’s a lot of very caring people. Everybody is there to have a good time but also to make sure they clean everything up and everybody feels like they’re welcome. It’s definitely a fun environment.”

Writer: Stacy Clardie, 765-496-0291, sclardie@purdue.edu

Media contact: Brian Huchel, 765-494-2084, bhuchel@purdue.edu

Sources: Carson Slabaugh, 765-494-3256, cslabau@purdue.edu

Philip Piper, piperp@purdue.edu