Student-developed communication network for UAVs interests NASA

Chatter usually radiates from Room 3175.

Apoorv Maheshwari and Hsun Chao have had many brain-storming sessions in that end-of-the-hall spot, nestled in Purdue’s Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering.

One will throw out a research topic, and they’ll debate for hours, dismissing possibilities, building on hypotheses.

“A lot of ideas just went into the garbage can,” Chao says with a laugh.

Until last November.

When Maheshwari and Chao, graduate students in Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics, started discussing the mounting problems surrounding communication between unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly referred to as drones, in large metropolitan areas – namely, the skyscrapers that prevent communication – they realized the topic actually merited a deeper look.

They read research that suggested because UAVs are expected to take over labor-intensive tasks, like package delivery, in the near future, an estimated 88 billion small drones are projected to operate in the Washington D.C. area by 2050. Most research about drone operation safety assumed reliable traffic information, but the research they read had no actual solution to that issue.

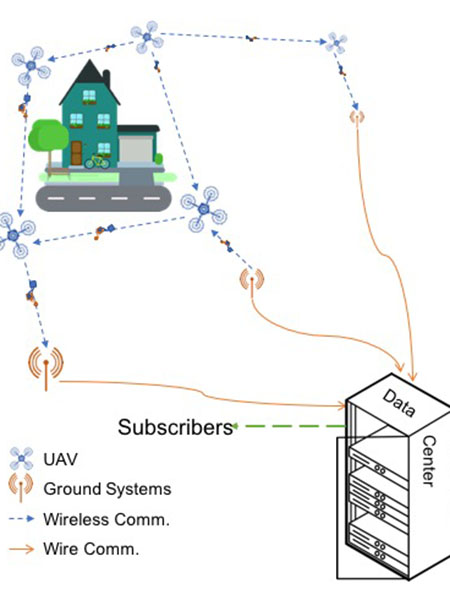

So Maheshwari, Chao, fellow AAE graduate student Varun Sudarsanan and Shashank Tamaskar, a postdoctoral researcher in AAE at the time, developed a communication framework that leverages blockchain technology to overcome challenges of operating UAVs in a city. Their “Traffic Information Exchange Network” (TIEN) would provide a data transmission mechanism for continuous real-time traffic data exchange while allowing drones to freely join and leave airspace. TIEN consists of three components: Onboard systems, ground systems and data centers.

The group entered its proposal in NASA’s University Student Research Challenge.

And was one of five winners selected by NASA.

But winning was only the beginning.

A new approach

As part of the challenge requirements, NASA asked winning groups to raise one-third of the direct project costs through a crowdfunding campaign. If successful, NASA will match twice that amount. For Purdue’s group, that meant to receive the grant award of $32,000, it has to raise $7,500 via crowdfunding.

“That will basically make up the whole research project from what we had in our proposal,” Maheshwari says.

As of late July, Purdue’s group had raised about 18 percent of their goal.

While attending an AIAA Aviation Conference in Atlanta in late-June – where the group shared booth space with NASA to raise awareness about the project – AAE students were told by a NASA technical monitor that they were the first to enter the crowdfunding phase out of all the teams selected.

“We told him that crowdfunding turned out to be more challenging than we anticipated, and he shared the same thing,” Maheshwari says. “We have a lot more ground to cover.”

But, at least, they can be encouraged by the feedback the proposal has gotten.

It’s largely been positive, they say.

The email that informed the group the proposal had advanced to the crowdfunding stage included a list of “strengths.” Among them, the idea of using blockchain technology. One comment about the proposal said blockchain’s “applicability and use in an aerospace application has yet to be attempted, but may very well be appropriate, if implemented correctly.”

Purdue’s group got that idea from Bitcoin, a form of electronic cash, that designed blockchain technology as its accounting method. Blockchain, generally, is a digitized, decentralized public ledger for all cryptocurrency transactions. Maheshwari says they were inspired by the technology, in part, because of the security it provides.

The idea is drones would carry onboard systems to exchange blockchains, containing relevant information, with each other. Ground systems receive the blockchains and share it with a data center. That data center collects the traffic data and shares it with stakeholders and other subscribed parties, such as the Federal Aviation Administration, UAV operators and researchers.

“A lot of people were asking why you need blockchain in this kind of communication?” Chao says. “The one key reason is because right now we have middle men to deliver the information. How can we make sure that the middle men behave correctly and honestly and follow our mechanism? So that’s where the blockchain come in to play. So whenever this kind of relay happens, each one of the UAVs can evaluate the credibility of its neighbors. So for those UAVs with very low credibility, we will just ignore the information. We only keep the information from the UAV that has high credibility. In order to keep your credibility high, you need to follow the rules we are developing as part of this project.”

The next steps

It's a new approach to attacking a relevant issue, Maheshwari says.

Dan DeLaurentis, a professor in Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics who was the advisor on the proposal, agrees.

DeLaurentis says there is “no doubt" the solution needed to unlock the future of unmanned aerial vehicles doing commerce lies in the ability to safely and securely manage the traffic amongst large numbers of vehicles.

“(This group’s work) already has shown promise as a potential solution,” DeLaurentis says. “(Chao and Maheshwari) are indeed the ‘crazy idea generators’ in our Systems of Systems Lab, and that is what makes me most proud of them because that’s where we want our Ph.D graduates to excel – dreaming up and demonstrating the biggest innovations of tomorrow.”

He cites an FAA report that says there were about 450,000 Undermanned Aerial System (UAS) users in May 2016. By the end of 2024, that number is expected to increase as high as 2.7 million users. Currently, there are 6,500 commercial and 210,000 general aviation aircraft operating in the U.S. national airspace, Maheshwari says.

“There’s so much research that’s focused on how you integrate UAS in the national airspace system. So our research is a step in that direction,” Maheshwari says. “How do you ensure that all these UAVs that are being operated at this lower altitude don’t interfere or integrate well with the commercial flights that you’re having? Because that number also will go up. You’ll have more commercial flights in the future. So how do you make sure they’re integrated well and don’t have any interference?”

The plan is to eventually file for a patent, but there still is work to be done.

After the group reaches its crowdfunding goal – people interested can get information here – the next steps for the project will be to write software, prototype UAV-TIEN hardware and build the system. They likely will need to collaborate with other departments as well for more simulations. For one, they’ll need UAVs for physical testing and to collect real-world data to see “if it really does what we think it should do,” Maheshwari says. One professor in Purdue’s School of Civil Engineering already told the group he’d assist in that. The group also met with Prof. Aniket Kate in Purdue’s Department of Computer Sciences who works in blockchain, and that feedback generally was positive as well.

“A lot of research says the UAV operation in the future will be a lot, and we need to ensure the low-altitude airspace safety,” Chao says. “There are so many skyscrapers, so that’s a challenge. If this technology happened, think about how the market will be opened by this communication.”

Like when Amazon’s “Prime Air” concept launches and drones drop off packages. Or when Domino’s is able to ratchet up its pizza-delivery-by-drone system.

Maybe TIEN could help make that possible.

Chao, for one, can’t wait.

“Yeah, sure, why not? I can just sit in my balcony and wait for the pizza,” he says, laughing. “It’s fantastic, right?”

Sources: Apoorv Maheshwari, apoorv@purdue.edu

Hsun Chao, chaoh@purdue.edu

Dan DeLaurentis, ddelaure@purdue.edu

Writer: Stacy Clardie, 765-496-0291, sclardie@purdue.edu

To support this project through crowdfunding, click here. The School of Aeronautics and Astronautics will match donations from AAE students, faculty and staff.