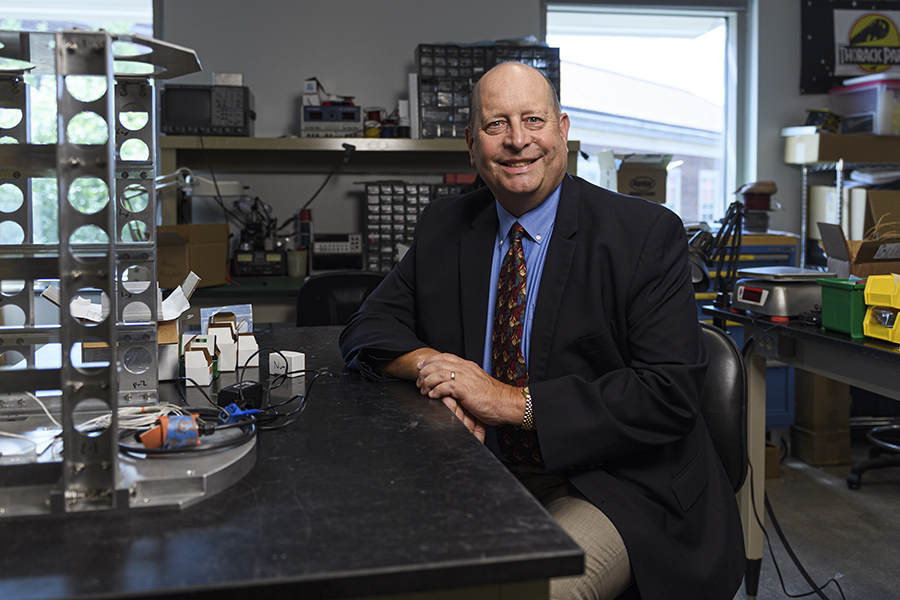

AAE faculty profile series: Steven Collicott

The enthusiasm radiated from Steven Collicott.

And Dan Radocaj was kind of in awe.

Radocaj had only been at Purdue University for about a month when he had connected with Students for the Exploration and Development of Space on a project. The student organization was working on a project with the Space Experiment Module, little containers that had flown on a Space Shuttle and been returned by NASA. The students needed direction on next steps — could they do another module? — so they asked one of the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics foremost authorities for help.

When Collicott entered Grissom Hall one evening in the Fall of 1996, he was joined by then-2-year-old daughter Sarah, carrying a toy. As Collicott settled in to talk about what kind of fluids project the students could put on their own Space Experiment Module, he borrowed the plastic, rectangular toy filled with water from Sarah. He turned it upside down, sending drops of red liquid down a ramp, across a wheel and down another ramp. Back and forth, the droplets flowed, across the bottom.

As he was showing how two liquids interacted and how the toy demonstrated fluid dynamics, Collicott spoke with passion.

“You could tell he loved what he did, from that first meeting,” Radocaj said. “When he took that toy, he was so excited to see how these little droplets were moving through it, and that enthusiasm is what he imparted to all students.”

That interaction set the tone for what Radocaj would experience not only the next four years as an undergrad but in the following 18 months as Collicott’s graduate student and research assistant and in the 22 years since.

Collicott’s passion exudes from his being, in how he purposely has found ways in teaching to break down complicated theory, in the effort he’s expounded in creating hands-on opportunities to prepare students for real-world application, in the patience he’s exhibited toward questioning, curious learners, in the intent listening, in the emphasis on building trust and respect.

The underlying intention: To cultivate relationships and persistently pursue them. First, with students, then transforming and growing, as they transition to alumni, to colleagues.

For as renowned as Collicott is within the aerospace industry for his research in low gravity fluid dynamics and as a leader in advocacy for suborbital commercial spaceflight — and he appreciates both of those roles — there’s little doubt from former students that his most profound impact is beyond research and engagement.

“It is very obvious he cares. He makes those personal connections,” alumna Shannon Fitzpatrick said. “Those personal connections are not fleeting. They don’t just end after you graduate or five years after you graduate. That’s pretty significant.”

Building personal connections

Like clockwork.

Never fails.

At some point in December, Shannon Fitzpatrick walks to her mailbox and among the stacks of Christmas cards, there’s always one from Steven and Jennifer Collicott.

And if that was the only time she heard from her former professor and advisor, that’d still be sweet, knowing she was in his thoughts. But Collicott isn’t satisfied with a once-a-year check-in.

Long before Facebook, Collicott developed a method of digital connection.

Family

Wife Jennifer, daughters Sarah and Rachel

Always makes time for ...

Woodworking, reading biographies and history, and golf. ("Because there are no good sailing lakes around here.”)

Did you know?

He was born at Home Hospital in Lafayette and spent his first few months at the then-new Hilltop Apartments while dad Howard completed Ph.D. work in mechanical engineering at Herrick Labs.

He collects information throughout the year about his former students, always on the lookout for updates. Sometimes professional, sometimes personal. He compiles all the updates into an email, sometimes even includes pictures, and he sends it to all of his former graduate students.

There usually are updates about his own research and current students’ research, too, but the intent of the group email largely is to shine light on alumni, whether it be promotions or research grants or wedding announcements.

“It’s better than Facebook,” Radocaj said. “He can tell me what all these people are doing, and he knows and he’s so proud of everything they accomplish. It’s phenomenal. He cares about his students. He puts them first. That’s probably why I still hear from him and I keep in contact with him. I knew he’d care about my well being, my career, my development as an engineer. He cared about that when I was an undergrad, when I was a graduate student.

“He built a strong relationship, my trust. That bond has stayed and survived for the last two decades afterward. And I’m not the only one.”

Rarely does Collicott let an opportunity to praise students, current or former, pass.

Radocaj said Collicott has nominated him for awards, and Collicott has invited Radocaj back to campus, too, to share insight with current students. That’s a form of appreciation, too, not just for former students but for current ones: Wanting to expose current students to real-world insight, wanting them to see how what they’re doing in AAE is directly applicable to industry and allowing alumni to take part in that educational process by paying forward their experiences.

But chatting up current students about accomplished former students isn’t the extent of Collicott’s bragging.

A couple years ago, Fitzpatrick was surprised to get a call at her desk from a co-worker at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility that relayed surprising details about her time in AAE. The co-worker, whom Fitzpatrick didn’t know all that well, told Fitzpatrick she had to give her kudos and offered respect for the path she took to get to Purdue.

How’d the co-worker know Fitzpatrick was the first in her family to go to college, that she had to battle skepticism from her family about her choice of aeronautical and astronautical engineering, that she had to put herself through school? The co-worker happened to be at the same conference as Collicott. When Collicott had a chance meeting with a small group and Fitzpatrick’s name came up, he shared stories about her journey, and others in the conversation celebrated her achievements as well, he said.

“The way she described the story he told is he painted me in such a grandiose light to everyone in the room, I became like their hero,” said Fitzpatrick, laughing. “I don’t remember telling him most of that, but I must have at some point. I was like, ‘It’s not that big of a deal.’ But he made it into a big deal. It was so profound to her, she felt the need to pick up the phone to call me to reflect the story he told. In a way, I was a little embarrassed, but at the same time, I realize he thought highly of me in that regard.

“He’s thinking of people, thinking of his former students. I got my master’s in 2003, and he’s still thinking of me. He’s still sending me an email out of the blue about a job opportunity or putting my name out there and sending me Christmas cards every year, which I just think is amazing.”

That kind of care and attention isn’t strictly applicable to students who’ve graduated.

Unique learning

Design, build, test education preceded Collicott’s arrival in West Lafayette. But he added his own flavor. With the explicit intent of providing students opportunities few other universities could.

And AAE418, “Zero Gravity Flight Experiments,” has been a resounding success, in the unique, hands-on experience it has offered, in the achievement of the projects connected to it and in the fairly exotic locations provided for testing the experiments.

Students from the course have tested their spacewalk tool designs in the Neutral Buoyancy Lab at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston as part of NASA’s Micro-g Neutral Buoyancy Experiment Design Teams program since 2014.

They’ve tested experiments aboard zero-gravity aircraft, while experiencing weightlessness themselves on the appropriately nicknamed “vomit comet.”

They’ve traveled the country to load their experiments into and watch them launch on suborbital rockets for Blue Origin, EXOS Aerospace and UpAerospace since 2009. And soon with Virgin Galactic.

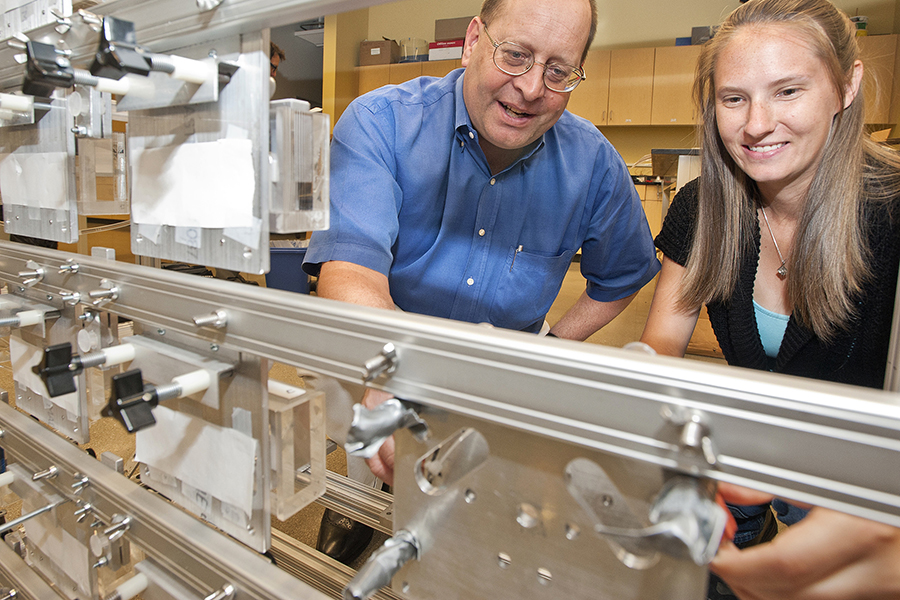

Students work on real-world experiments that basically are part of Collicott’s research career. It’s not a lab-class experiment that’s set up to teach a small number of topics in a nicely focused way. It’s open-ended interactions with launch companies, vendors and machine shops.

“I think that really just makes it attractive to a lot of people, makes it memorable,” Collicott said.

There are plenty of students to echo that sentiment.

Collicott has had more than 1,100 students in 418, he said. That’s pretty impressive, especially considering it never was intended to develop into this.

When AAE students Michelle Lucas and Chet Kumar came to Collicott in Fall 1996 asking him to be their advisor on a project for a new NASA program, Reduced Gravity Student Flight Opportunities, he said “yes.” But it was just a side project, not for course credit, and he figured it’d be a one-time thing. He was just happy to help the four-member team on his own time.

But after “The Study of Fluid Sloshing in a Low-g Environment” was designed and students tested the experiment in low gravity aboard NASA’s KC-135A aircraft, Collicott knew this was work worth doing consistently.

There were more independent study projects over the next several years, and before the 2002-03 academic year, Collicott officially pitched a course. Now, “Zero Gravity Flight Experiments” is offered in the fall, spring and summer semesters.

An example of a parabolic flight experiment from the class is Collicott’s current “Conformal Tanks” payload. The opportunity to propose the work for NASA Flight Opportunities funding came from the recognition that the current trend for satellites to be made smaller requires components to be smaller, but propellant tank walls are very thin in large satellites. Propellant tanks for small satellites are generally far stronger than needed, so they don’t need to shaped as traditional minimum-weight pressure vessels like in the large satellites. Small-sat propellant tanks often can be shaped to fit around other components in the satellite, and the new shapes require new solutions to properly control the position of liquid propellants in weightlessness and deliver gas-free liquid to the thrusters.

AAE418 also builds experiments to fly in commercial reusable sub-orbital rockets. The “Cryo Gauging” payload from 2019 is typical. It studied a pair of interesting geometrical details that could cause unexpected liquid positioning in a cryogenic propellant tank in zero-gravity. The experiment, built by Collicott and his students, was created to support NASA’s large Radio Frequency Mass Gauging experiment on the International Space Station. The automated experiment on the Blue Origin rocket — one of seven experiments that have flown on five Blue Origin New Shepard missions — successfully delivered the data that was sought.

Collicott is vocal about how this new era of spaceflight research opens doors to many new users of spaceflight, and AAE418’s Zero-gravity Glow Experiment, or ZGGE, was the first of its kind. When a local second grade class asked Collicott if fireflies could glow in space, AAE418 collaborated with that class to build an experiment to mix the actual firefly chemicals while in weightlessness on a Blue Origin flight. Collicott led the local fundraising that demonstrated how a K-12 school can fund its own experiment, leading to the “Purdue School Launchbox.” The Launchbox is available for schools to pursue their own K-12 experiments and affordably fly a small payload to space and back.

“That hands-on work and experience is one of the best things he has to offer students. You can’t beat real-life projects,” said Emily Beckman, who recently completed her master’s work with Collicott.

The projects from the course, mostly, come from Collicott. The variety and vastness of that research isn’t surprising to Fitzpatrick, for one.

“He has a tremendous amount of creativity,” Fitzpatrick said. “The one thing that always stuck out when I was working with him doing my thesis is he just had a phenomenal number of ideas. I remember when he was first talking about what project I’m going to do, and he would just rattle off all these ideas. I don’t know where he came up with all of them. It’s like he had a laundry list he kept. All of his ideas were always pouring out, so there was never a shortage of what will we do next or how do we design and develop this propellant management device. He always had a slew of potential designs.”

There are no signs of slowing down either.

In November 2020, Collicott and senior Daré Adebonojo were the 182nd and 183rd AAE flyers on a zero-g flight with AAE418’s 40th payload. There have been 5,439 zero-g parabolas, 222 lunar parabolas and 179 Martian parabolas throughout the course of the class. In December 2020, a team from 418 was selected to test its tool in NASA’s NExT competition in June.

Those are the dramatic payoff for the work.

But Collicott tries to make sure the process is enjoyable, too. Part of that is how he teaches material in a classroom environment and part, too, is how readily accessible he is outside of it, past and current students said.

“AAE418 was really unlike any other class I have had,” said Logan Walters, a current graduate student of Collicott’s. “Due to the number of teams, work was mostly independent. Despite this, we never felt like we were without direction, as we regularly met with Dr. Collicott and he was always available for questions. AAE518 was more like a normal class than AAE418, but at least when I took it, a bit of this project-based approach was still present. The class was split into groups, each of which tackled a unique problem relating to low gravity fluids modeling that we worked on throughout the semester.

“I think this project-based approach is really what characterizes his teaching style — taking concepts learned in coursework and applying them to an independent project.”

Radocaj and Fitzpatrick, who were graduate students when Collicott’s office was at the Aerospace Sciences Lab, remember him frequently popping by to check on their graduate work and being quick to answer questions.

That’s still the case, said Walters and recently graduated Beckman.

“I learned that going to ask him a question about something you’re struggling with is a better idea than being stubborn and trying to figure it out yourself,” Beckman said. “One time, I was trying to get good video of slosh in a clear propellant tank, but my surface identification code was having trouble picking out the surface from the background. After a while of thinking my code was the issue, I went to show Professor Collicott. Within a second, he had identified that my problem was that I didn’t have enough backlighting. I ran the experiment again, and everything worked perfectly.

“It is important to do your own research and not expect to be spoon-fed information but asking questions of people with experience in also invaluable. I love how Professor Collicott seems to be very available to students. When I, or students in his classes, needed to ask him a question, it was easy to get an answer.”

Collicott was happy to oblige — he started seeking answers about aerospace when he was a kid.

The path

How could Steven Collicott not be captivated?

He was a child of the Moon race, growing up in Michigan in the 1960s.

As a kid, he’d use Tinker Toys to build skeleton-framed spaceships. As a first-grader, he and a friend drew Saturn V rockets for an assignment. Engrained in his memory is exactly where he was sitting on the floor at his childhood home in Ann Arbor to watch the Moon landing in 1969.

Collicott jokes he doesn’t know how anyone his age grew up to be a doctor, lawyer or dentist. He briefly held dreams of being a major leaguer, but those were dashed early, too, after an “0-for-1972” summer of little league.

“Space was a fascinating thing when I was young. And still is,” he said. “I took to it.”

Collicott’s inclination as a natural tinkerer — more than once, he dismantled a typewriter and put it back together when he was in second or third grade — and interest in STEM helped turn that fascination into much more.

He was involved in the Academy of Model Aeronautics, teaching him craftsmanship, patience and aerodynamics. In high school, he gravitated toward math and science. He was ready to pursue aerospace engineering in college.

Collicott stayed in his hometown, Ann Arbor, for college — that was the caveat for his parents paying for it, even though dad Howard was a Purdue mechanical engineering graduate — and he quickly was introduced to experiments and internships. A spring break trip for the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics as a sophomore led to an internship with Lockheed Missiles and Space Company in 1981, where Collicott got his first exposure to zero-g fluids experience while working with propellant management systems in satellites and missiles.

He thought, “Man, I want to do that. And I want to build satellites and spacecraft.”

He asked a young assistant professor at University of Michigan, Jim Driscoll, “If I want a career in fluids research, what topics should I pursue?” Driscoll’s response: “If you become an expert in two-phase flows, you’ll never be short of work.” But two-phase flows weren’t part of the aero curriculum. So Collicott got books to study the subject. And then decided it was too messy. He didn’t want anything to do with it.

The next summer, Collicott had an internship with McDonnell-Douglas Research Labs in St. Louis, working on aerodynamics research.

He thought, “Man, I want to do aerodynamics research.”

Throughout most of graduate school, earning a master’s and Ph.D. at Stanford, Collicott envisioned he’d return to McDonnell-Douglas. But the company started closing labs. Collicott had spent a couple semesters working as a graduate teaching assistant and got good feedback: Students said he was helpful and explained the material well.

He thought, “Maybe the professor route is the way to go. I get to do research, and I get to teach.”

He moved to West Lafayette on New Year’s Day in 1991 and started as an assistant professor in the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics the next day. His lab was at ASL at Purdue’s airport. His research focus was optical diagnostics for a wind tunnel — far from two-phase flows — and his first large grant was from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research in partnership with Professor Steve Schneider for a Mach-4 quiet flow Ludweig tube.

“That work got me to associate professor level, and I knew to go to the next level, I really needed to have my own research program,” Collicott said. “That coincided with when I kind of rejuvenated an interest in low gravity fluids work.”

No one else at Purdue was doing zero-gravity fluid dynamics — control, gauging and modeling of liquids in the weightless condition of space. And the uniqueness of two-phase flow — gas and liquid — appealed to him, even if it occupied an obscure corner of the fluid dynamics world. All gas or all liquid in a container is “boring,” but two-phase flow problems aren’t, he said.

A small contract to work on the liquid helium tank of the Gravity Probe B spacecraft design for Lockheed produced connections and led to a sabbatical in 1998. Then, “it just took off from there,” Collicott said.

“It just seemed like there was a niche I could fill, that I would enjoy working in,” he said. “I didn’t have to worry about stepping on anybody’s toes on campus.”

And the shift was complete. To a path and a topic he’d initially dismissed at Michigan, when Driscoll first revealed the logical nature of it.

“He uttered an oracle, and I couldn’t escape my destiny,” Collicott joked.

The research stays interesting, too, because even though liquids have been flying in space for 60 years and there’s a long history of what works to build on, there still are many new things to explore. That’s important for the lifelong “tinkerer,” on a quest for answers.

But Collicott keeps his interests piqued in others ways, too.

Inspirational leader

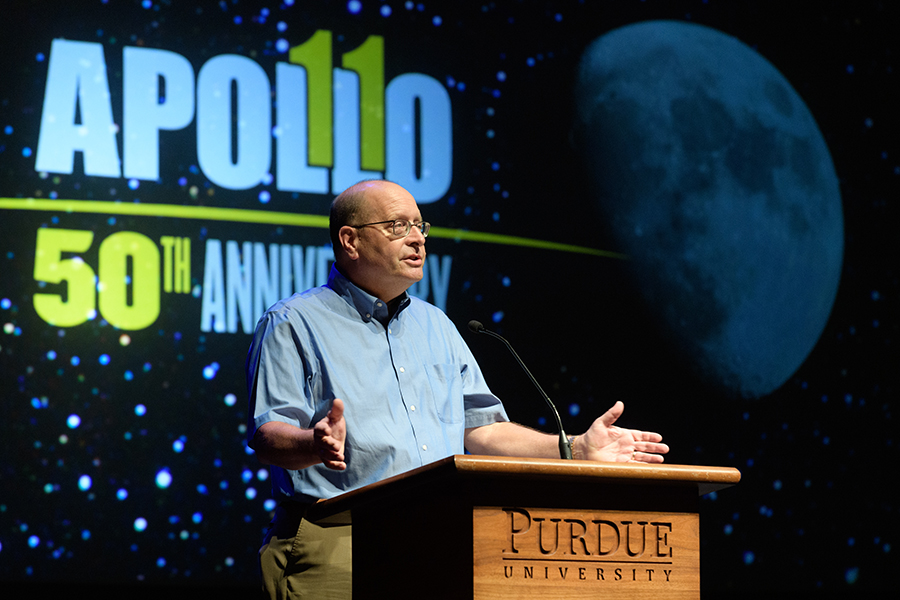

On May 16, 2013, Steven Collicott found himself sitting in front of the Senate Sub-Committee on Science and Space, testifying about the merits of private-sector space enterprise and the positive impacts of suborbital research, in the Russell Senate Office Building.

It’s not exactly something he could have predicted.

“A big surprise,” he said, as it relates to the national advocacy role he has assumed. “It’s something else I never set out to do. When I was younger envisioning myself as an aerospace engineer, I thought, ‘Build some really cool things that fly faster and higher,’ and all that stuff. The notion that I would be running around the halls of Congress, talking to non-engineers, non-aerospace people about making use of this new commercial, reusable suborbital rocket industry for doing research? It feels very different from what I thought I’d be doing as an aerospace engineer.

“But the benefits of this new market, this new industry are quite big, for both research and education. NASA and I can fly an experiment on one of these vehicles for a few percent of the cost of an old-style suborbital rocket. It’s pennies on the dollar, compared to the traditional method, so we can get so much more science done so much more affordably.”

Since 2008, Collicott’s trips to D.C. have been with the Commercial Spaceflight Federation (CSF), largely in conjunction with the CSF’s Suborbital Applications Research Group (SARG). SARG is comprised of experts throughout the aerospace industry committed to enhancing the experience and opportunities within the suborbital industry. Collicott became chair in 2013 when Alan Stern, the founder and first chair, had to devote all of his time to the arrival of his New Horizon spacecraft at Pluto.

Once a year, SARG visits the Capitol to meet with U.S. Senate staffers, House staffs, Office of Management and Budget staff and National Space Council staff to offer insight into new affordable research and education opportunities in spaceflight.

Eric Stallmer, CSF’s president from 2014-2020, has seen firsthand how effective Collicott is in speaking to those specific audiences — by taking the most detailed scientific research that is performed in suborbital space and putting it in terms the policy community can understand.

“Steven has been at the forefront of leadership in the suborbital community. At CSF, he was our go-to expert on the matter,” Stallmer said. “It’s hard to measure how large his impact has been on raising awareness of the extremely valuable work that goes on in the suborbital research community. What is bigger than enormous? That would be Steven’s impact.”

When the Suborbital Applications Research Group comes to D.C., Stallmer says they fill congressional committee rooms because people look forward to hearing of the cutting-research work they’re doing.

“His excitement for the research that his students are conducting is really contagious. It makes everyone around him excited and leads to a tremendous ‘buy in’ to the critical work that is being done in the suborbital community,” Stallmer said. “He really is an inspirational leader.”

A legacy

Steven Collicott had a somewhat startling realization in December: He has spent more than half his life as a Purdue professor.

Not that any of the enthusiasm has faded since Day 1, more than 30 years ago.

When Fitzpatrick was on campus to speak in 2019, she encountered the same boundless-energy Collicott she remembered. Accompanied by her then-7-year-old son Tyler, they had trouble keeping up with the brisk-walking, bounce-in-his-step professor during a tour of campus. Collicott’s “bounding,” as she calls it, was in full form.

It’s how he traverses the hallways of the Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering now, eager to get in front of students to teach the next class, eager to get to the lab to offer guidance for hands-on research.

Each student another who is impacted by his leadership, dedication and love of aerospace engineering, space and fluid dynamics.

Each student another young engineer he guides, molds and affects with his intentional attention.

Like Fitzpatrick, Radocaj and almost literally countless others. At least by Radocaj’s estimations.

“All these students every year, he excites them, he teaches them, he makes them a better engineer, he makes them a better leader, and he affects that one person. Well, he does that every semester times 30 years. That’s a big number,” said Radocaj, a commander and U.S. Navy Test Pilot. “Those students have gone out and taken what they’ve learned from him and spread that. It’s this exponential growth of affecting the world.

“That’ll be the legacy that he will leave behind.”

Dr. Collicott's enthusiasm is immediately obvious as soon as he starts talking about any of his projects. His enthusiasm makes it easy for me to get excited myself, and if I ever have questions, I know they won't bother him in the slightest.” – Current graduate student Logan Walters

He taught me to take care of people. I have always carried that. Anybody below me in the chain of command, I go out of my way to make sure their accomplishments are recognized, that their good work is appreciated and thanked, to make sure that not only are they professionally doing well and doing well personally, that both of those are taken care of. That’s a leadership quality that has nothing to do with being an aerospace engineer. And I learned that from Professor Collicott. Hopefully everyone I go out and influence learns that same thing he taught me.” — Alumnus Dan Radocaj

Steven started at Purdue just a year or two after I did. He developed a vision for working on low-gravity fluid dynamics for spacecraft applications, back when very few people were doing this. He's always been very motivated to involve both undergraduate and graduate students, and help them learn how to design, built and test actual working hardware. It's been great to see how he brought these two things together to meet a need that became widely evident only many years after he started working in the area.” — AAE Professor Steven Schneider