On a mission to save lives, AAE alum develops device to help train pilots

Every time Nick Sinopoli hears another story, he feels burdened.

Another tragic helicopter accident, another death that, he thinks, could have been prevented.

Spatial disorientation, a loss of perspective that can lead to fatal consequences, is a pervasive issue for pilots.

It’s taken the lives of well-known public figures — leading to John F. Kennedy Jr.’s plane crash and death in July 1999.

It’s taken lives of Sinopoli’s friends — Rusty Aaron in Fall 2012, when Sinopoli still was a student in Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

It’s taken lives of sports icons — Kobe Bryant’s death, a year ago on Jan. 26, likely will be found to be a result of the pilot suffering from the condition when the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board releases its final report of the accident.

Each time it happens, Sinopoli’s heart is spurred. Each time, his passion is ignited. A solution must be found.

Sinopoli, who completed his bachelor’s from AAE in 2012, thinks he’s developed one.

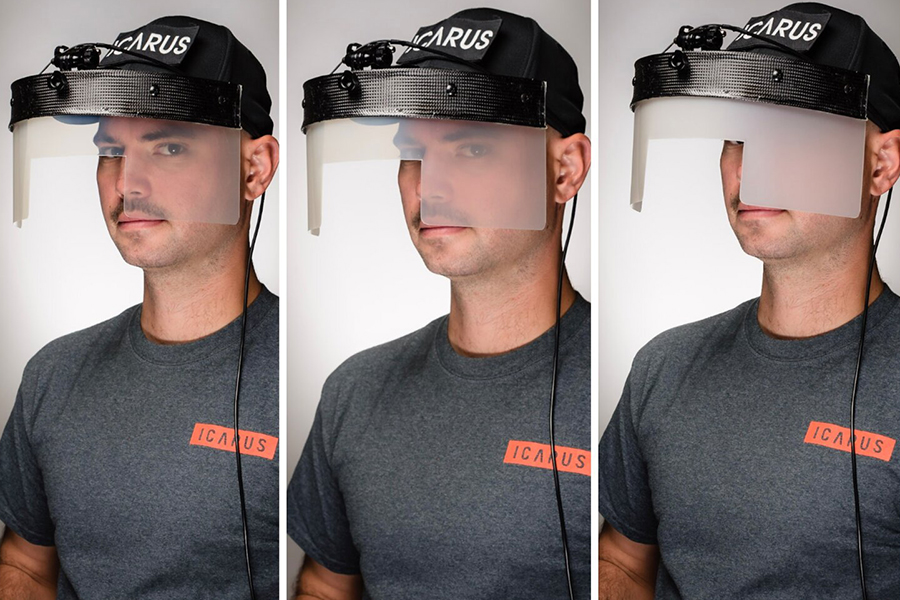

Early accidents planted seeds for what became Instrument Conditions Awareness Recognition and Understanding System, or ICARUS, a visor and accompanying app that helps pilots train for transition from visual to instrument flying in a more accurate way, with a higher-fidelity simulation. The device integrates hypothetical weather scenarios and allows the instructor to surprise students with degraded visual conditions.

The goal: To beat spatial disorientation.

Sinopoli said ICARUS can do that by combining the visual realism and control of a flight simulator with the inner ear feeling and pressure of actual flying. Allowing pilots to experience all the inputs that cause spatial disorientation in a safe training environment is key to reducing the accident rate, he said.

“Simulators can’t replicate the actual sensation of flying,” said Sinopoli, a captain in the Wisconsin National Guard who flies the UH-60 Blackhawk. “The hood, I know it’s coming on or off, and a lot of them are one size fits all. The difference in ICARUS is it’s controllable, and it changes opacity. It’s a digital solution to the analogue predecessor. The advantage is the instructor can control the situation.

“It’s basically bringing a simulator into the cockpit.”

Pursuing passion

Nick Sinopoli knew he had to do it.

But that simple fact didn’t lessen the pain. He’d invested so much in that 1999 silver Porsche Boxster, bought it for $5,000, fixed up and loved every moment. The sweat stains long dried that had been dripped replacing the brakes, the stiff back from laying on the creeper under the car long loose, the grease-stained arms long cleaned.

Restoring the car gave Sinopoli peace, afforded him the opportunity to use his hands to tinker, the engineer embedded in the interworking. But the respite, the joy even, was for him. It wasn’t broad reaching. The device he could have been tinkering with, could have been perfecting, his ICARUS idea, if he had the money, could actually save lives.

Could have saved Aaron’s life, maybe.

So, even though all his family and friends told him he’d be crazy to part with the Porsche, Sinopoli listed the car he’d pulled out of a barn in Mississippi in 2014. He sold it in 2015 for $10,000.

That money was invested in to ICARUS.

After graduating from Purdue and the Navy ROTC in December 2012, Sinopoli reported to the Naval Air Station in Pensacola. He’d finished his pilot’s license at Purdue, right before arriving in Pensacola, but he’d been flying since he was 17.

While in Pensacola, he was flying one day under the hood — a piece of paper jammed into his helmet to block the view outside the helicopter — and got flustered when his instructor grabbed the controls from his hand to avoid a bird. As they were walking away from the aircraft that day, Sinopoli thought of the then-new Boeing 787 and its windows that changed opacity at the push of a button.

“I wondered, ‘Why can’t we use something like that?’” he said.

Sinopoli bought Dispersed Liquid Crystal (PDLC) film on the internet about six months before parting with the Boxster. It was $300 — and he wasn’t sure it was worth it. But when he received the film to electronically alter the pilots’ visibility, he realized switching between visibilities looked a lot like going into clouds. That changed his perspective on what his device could be.

Initially, he was concerned with being able to see outside quickly, when a pilot needed to look for traffic or dodge a bird. But he remembered a Marine Huey pilot told him that going inadvertently into “Instrument Meteorological Conditions” — when weather conditions require pilots to fly primarily by reference to instruments rather than by outside visual references — was scarier than getting shot at in Afghanistan.

“That was the secondary ah-ha moment,” Sinopoli said.

Boilermaker influenced

When Sinopoli began the prototype process from his garage, he drew from his Purdue days. As a senior, he spent countless hours in the second-floor workshop of Neil Armstrong Hall, working on aircraft for a Design, Build, Fly course.

The first few years of the device design, Sinopoli tried to make a set of glasses. He has since switched to visors. But, up until recently, Sinopoli still was using carbon fiber techniques he learned at Purdue to produce the visor frames.

“I would say the intangibles of persistence and work ethic are by far the most important. Grit will get you anywhere,” Sinopoli said. ”I learned time management the hard way at Purdue by being in AAE, Navy ROTC and Phi Delta Theta.

“My AAE education also taught me to solve the root of the problem and always strive to improve, which has paid dividends during beta testing.”

Though Sinopoli had graduated from Purdue by the time the idea really took root, coming back to his roots in West Lafayette fueled early ideas and prototypes for ICARUS. He even designed a gold-and-black device in that beta stage.

Purdue always had a familiar feel. Maybe because, even though Sinopoli grew up in Austin, Texas, he heard about Boilermaker country so much. His dad, Jim, was a Boilermaker, received his degree from AAE in 1970. Though Jim didn’t work in an aerospace engineering field — he worked in telecommunications, traveling all over the world engineering smart buildings — he spoke of his time on Purdue’s campus often. And fondly. That’s partly why Nick ended up in Indiana, transferring to Purdue after his freshman year.

Though Jim’s health is deteriorating — he had a stroke six years ago and is in the latter stages of Alzheimer’s disease — “Boiler up” still remains a part of his lexicon.

It’s beyond words that Jim was able to see his only son secure a patent for the potential life-saving device and equally meaningful that Jim saw Nick put on his wings, too, before the dementia took hold.

“My dad loved Purdue,” Nick Sinopoli said. “I kind of came home to Purdue. I found not only people to help me out but to take me seriously and offer great support throughout the process.”

Persistence personified

Boilermakers certainly are known for their persistence, and that ingredient has been key for Sinopoli. He’s had doubters along the way.

After an article about ICARUS appeared in Vertical magazine, the leading helicopter publication, someone commented, “Why would I use that? I can use the hood that has been around.” Sinopoli heard and read similar comments elsewhere. He quickly learned aerospace is ruled by “giant corporations” and aerospace innovation can rarely come from startups. He wasn’t surprised to hear, “Good luck, kid.”

Sinopoli admits at times, he thought, “Why don’t I just do something else?”

“But every single time that happened, when the path might have shifted, I always knew that it was something I needed to do. I knew it was the right way,” he said.

On April 24, 2015, he had built an initial flyable prototype that flew over Purdue. He made a video that got him into an accelerator at the Oshkosh Airshow in Wisconsin, and with it, some funding. Much of the initial beta testing for the device was done by Purdue’s flight program, along with Ohio State.

He secured a patent in September 2016 and nearly five years later, Sinopoli knows letting go of that Porsche was one of the best decisions he could have made.

ICARUS in being used in several helicopter flights schools, a police department and a foreign military now, he said. Sinopoli continues to meet with universities and industry to get the device more broadly distributed. Because he believes it can be impactful to pilots, believes it can create better pilots, believes it can keep pilots — and their passengers — alive.

Sinopoli’s persistent pursuit may have initially been borne from necessity, but it quickly transitioned to passion.

“I want to give all pilots the best training possible and prevent accidents that killed Rusty, Kobe Bryant and countless others,” he said.