A look back at Engineering Sciences: An analytical approach

Tom Brandon was a mechanical engineering student at Purdue in the late 1950s when he heard the university had added a new engineering program.

On a trip home to South Bend, Tom made sure to not only mention it to younger sister Nancy but also to offer a bit of a challenge.

“They’ve never had a girl graduate from it,” he said, prodding the sister who always loved math but was intrigued by engineering.

Tom’s urging wasn’t necessarily why Nancy chose that new program, Engineering Sciences — one she called “perfect” because it was a more analytical approach to engineering instead of hands-on — but proving a point didn’t hurt.

Nancy certainly did that.

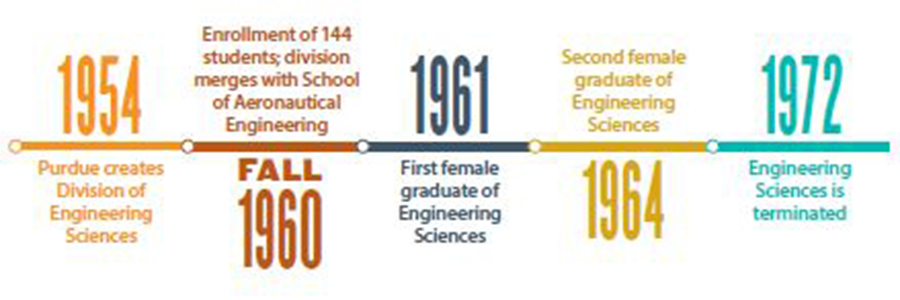

She became the first female graduate of Engineering Sciences in 1961, just one year after it merged with the School of Aeronautical Engineering. The merger lasted until 1972, after which the school changed its name to the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Ultimately, Nancy Brandon Anderson retired as Director of Technical Operations for Hughes’ Space and Communications Group after 21 years with the company. She served on the aero school’s Industrial Advisory Council until her retirement. In 2007, she was selected as an Outstanding Aerospace Engineer, a distinction given to the most illustrious graduates of the school.

Anderson was only one of many accomplished alumni in Engineering Sciences.

Five graduates have been selected as Distinguished Engineering Alumni: Jack Daugherty in 1977, Robert Hostetler in 1982, Ronald Kerber in 1988, Chris Whipple in 2004, and Janice Voss in 2012.

Ten have been named Outstanding Aerospace Engineers. Daugherty, Hostetler, Kerber, and Voss all were in the 1999 Class of OAEs. Steve Lamberson was selected as an OAE in 2002; Whipple in 2004; William Schmitendorf in 2005; and Jerry McElwee in 2006. Michael Hyer joined Anderson in the Class of 2007.

Engineering Sciences was aimed at providing students with a deep and broad grounding in both engineering skills and basic sciences. Graduates went on to wide-ranging professional careers, whether it be president and CEO of a manufacturer of electronic components and subsystems (Hostetler); vice president of advanced systems and technology for McDonnell Douglas Corporation (Kerber); an astronaut who flew in space five times and traveled 18.8 million miles (Voss); an innovator in theoretical and experimental research and development in plasma physics, high-voltage electron devices, gas discharge physics, lasers, and laser kinetics (Daugherty); risk assessment and environmental analyses gauging risks associated with energy production, fuel emissions and radioactive wastes (Whipple); among many others.

“It had the reputation on campus as being the hardest school, so maybe that was the attraction,” said Lolitia Beaty Bache, a 1964 graduate who started her career with the National Security Agency as an analyst, switched to programming, and retired in 2011 as a senior software engineer.

Regardless of vocation, the rigorous Engineering Sciences curriculum served its purpose.

“It prepared me very well,” Anderson said. “The reason I stayed to get a master’s is I was young when I started college, and when I graduated, I did not feel ready to face the big, bad world, so I went to summer school and started an extra year really specializing in what I wanted to do. I felt like conquering the world then, and I ended up in California in the aerospace industry.”

Engineering Sciences had 144 students enrolled in Fall 1960, the first academic year it merged with aero, compared to 193 in aeronautical engineering. The programs had separate heads until 1967 when Hsu Lo became the sole head over both programs.

A common curriculum was difficult to achieve because of the disparity in objectives of the two programs, and, ultimately, that’s what led to the termination of the engineering sciences program in 1972. Students who remained in the Engineering Sciences curriculum continued until graduation, and the difficulty of the coursework never lessened. Students needed at least 132 hours to graduate, depending on academic year.

Almost all of the classes were dual-level undergraduate-graduate classes, too, said Anderson, who received her master’s in 1962, one year after her bachelor’s.

“It was killer,” Anderson said with a laugh. “It’s one of the reasons I was able to get my master’s degree so quickly because I had enough other graduate classes. We were all very busy. It was tough. I had better than a B average, and I was in the lower half of my class. Does that give a clue of how competitive it was?”

The coursework didn’t only test Anderson, though — it also piqued her interests. Her major professor in graduate school was Lo, whose specialty was in orbit mechanics, and she was happy to take any courses related to space, she said. Ultimately, she spent the entirety of her career involved in satellites with The Aerospace Corporation, Rockwell International (now part of The Boeing Company) and Hughes (also now part of Boeing).

There were plenty of other courses that proved challenging.

Frank Siepker, a 1961 graduate, said he had eight semesters of math as an undergrad, including advanced courses that included master’s math students. In some semesters, he took 21 credit hours. He remembers another with six three-hour courses and a two-hour lab. He had a couple courses in mechanical engineering, thermodynamics, electrical engineering, aerodynamics, an introduction to digital computers, and internal combustion engines, among others.

“It was very rigorous,” said Siepker, who opted for law school after receiving his bachelor’s and was an attorney for more than 40 years in Illinois. “The courses were difficult. The theory was complex. It was 90 percent theory, no hands-on application, except our lab we had. It developed those analytical thinking skills.”

Bache, who married a fellow Engineering Sciences student, initially came to Purdue with the intention of becoming a math teacher. She was in the same sorority as Anderson and switched from math to Engineering Sciences as a junior.

She worked hard in the program, appreciated the quality of teaching and especially liked the smallness of the major, which allowed her to get to know her classmates well.

“I got a really good education,” said Bache, one of only two women in the Engineering Sciences Class of 1964. “The diversity of the Engineering Sciences program served me well. Scientific programming, which I eventually did after I left NSA, was very dependent on math. Part of my concept of ESE and my attraction to it was that it was essentially ‘applied math.’ It also allowed for a lot of flexibility in my working career.

“My Purdue experience prepared me well for later in life. I always worked in a field where there were way more men than women, and most of the time I was the only woman on the team. My experience at Purdue gave me the confidence I could hold my own in all those situations.”

Like Bache, Anderson said she never experienced discrimination by faculty and always felt “part of the group.” Anderson did notice, though, one advisory professor whose enthusiasm increased once she reached junior year, perhaps an indication he knew she was around to stay, she said.

“It was an excellent time, good people, good classmates,” Anderson said.

This story originally published in the Fall 2019 Aerogram.