TracSat project provides AAE undergraduates with hands-on experience

One AAE course is producing unique project-based learning opportunities for undergraduate students while also creating a testing bed that will aid the department in future small satellite projects.

With the help of an AAE alumnus, what started in Fall 2018 as an option in AAE590 “Space Flight Projects” is now its own course offering this spring. AAE590 TracSat Design Project is led by Alexey Shashurin, an assistant professor in AAE.

Alumnus Mike Dreessen, the executive director of Missile Defense and Space Systems Engineering at General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems (GA-EMS), wanted to establish a program for undergraduate students to get hands-on experience creating and testing small satellite systems and subsystems. That led to conversations with Tom Shih, J. William Uhrig and Anastasia Vournas Head and Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and, ultimately, Shashurin. The latter discussion produced the TracSat program, an opportunity for students to work with every subsystem that exists in an aerospace vehicle.

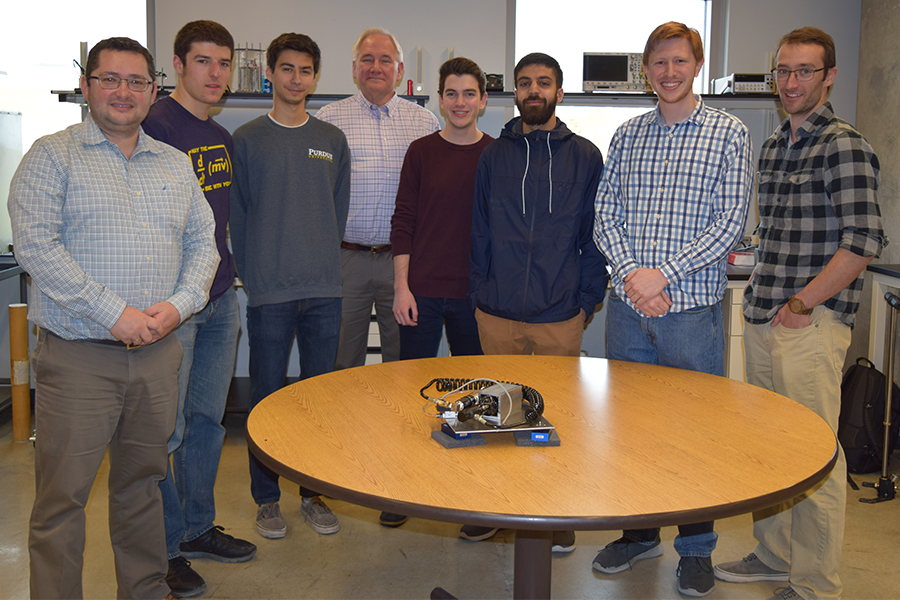

Just over one semester in, the course already has proven to be a special experience for undergraduate students Benjamin James Davis, Leonardo Facchini, Pol Francesch, Joe Kezon, Adam Patel, Glynn Smith, and Peter Waller, and, even, grad mentors McClain Goggin and Aaron Pikus.

“Some of them have experience on some of these projects before, some of them don’t, so it’s a big learning experience, and that’s a good thing,” says Pikus, who will complete his master’s work in May. “That’s one thing I really think more students should do is these sorts of projects, more real-world aspects. First, you have the concept that we’re going to build a CubeSat that’s going to float, move, and track objects. That’s all we know. Then going from that to how do we actually do it? So then start sketching stuff up on paper. Making ideas. OK, now we have this idea, it seems feasible, let’s see what parts can fit in here and then how do we put all this together to build something that’ll work? There are all these phases you go through that you don’t get in a normal class environment. That’s something I think all the students benefit from a lot. That’s kind of the evolution that sort of changes how you think about these projects.”

TracSat is a levitation base that provides a low-friction testbed for small satellites 2D maneuver testing and demonstration. A 2U CubeSat is uncoupled from the levitation base and houses all components for autonomous maneuvers.

In the fall, students accomplished a set of goals: Building a prototype, being able to translate on a low-friction surface, and having something that can actuate, such as magnetically latching valves for propelling the platform. This spring is focused more on coding, senior Smith says, by getting into the controls, being able to move it a certain way, being able to rotate it, and being able to do the target tracking maneuvers moving across a table.

But not just any “table.”

The testing for TracSat is being done on a 6,500-pound, 4-foot-by-8-foot, fine-polished granite slab inside the Structural Dynamics Lab in Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering. The table provides a large-area surface that uses air bearings to allow the satellite to float without friction over the surface.

“The whole idea with TracSat is to build a satellite that can be tested on the ground, and using the table, be able to control how it moves much like it would in a space rendezvous mission,” Dreessen says. “While it can’t be moved up and down, the satellite can be moved to educate students on propulsion, guidance, navigation, and control. While in a laboratory environment, students need to set up tests to tackle issues and start doing some remote sensing — all of the things you would do if the satellite was actually in space.”

Tackling issues is part of the TracSat real-world learning experience.

One unexpected development — at least for the underclassmen in the class — was just how long it took to get parts delivered. Delays happen frequently in industry, especially when parts, like those found on TracSat, are made to order. That was a shock to some students — some air bearings didn’t come until early this spring — but it also was a considerable teaching moment.

“We had sophomores, literally people the first semester in aero, the first class they had probably taken in aero, and they’re doing this. That’s awesome,” Smith says. “You have no idea what’s happening, but they will be so far ahead compared to everybody else who is not doing something like this. Being able to have undergrads on it seems like a huge deal. I’ve seen undergrads work on it, but building it, being heavily involved in its process, is very cool.”

Students opted to use a cold gas thruster, which is high pressure gas run through a nozzle, for the satellite’s propulsion. They plan on having a compressed air tank on board that will be, most likely, in the test base. They’ll feed air to that from thrusters that are on the CubeSat.

While the step beyond theoretical textbook learning is crucial, the course has offered another element that has served students well: Dreessen’s involvement.

The program is funded by GA-EMS, and Dreessen (BSAAE ’83) has been an active participant. He suggested developing the system and formulated the direction, Shashurin says. It was Dreessen’s idea to go for target acquisition maneuver for testing and demonstration of propulsion, sensors, and control algorithms on the low-friction surface testbed.

“It’s always nice to have a project driven by industrial needs,” Shashurin says.

Dreessen is present on-site as often as possible. He made several trips to campus during the fall semester to check on students’ progress and to speak to several classes. This spring, Dreessen will be honored as an Outstanding Aerospace Engineer and will participate in Industrial Advisory Council meetings in April on campus, and he also plans to check in again on the progress of TracSat.

Smith couldn’t quite put into words the impact Dreessen has had on him and other undergraduate students.

“He is awesome,” a smiling Smith says. “He’s just so incredibly knowledgeable. It comes with the territory, where he is, what he’s done. Just being able to discuss the issues, like we had a sit-down at the end of the semester, he’s reassuring us the path we’re taking, what we’re doing, the decisions we’re making.

“He is giving far more than we would ever hope for, and there’s no comparison for that in any project. It’s awesome having GA-EMS and him.”

Dreessen enjoys the interactions perhaps as much as the students. While he was a student at Purdue, design, build, test courses didn’t exist. Dreessen understands the value of the hands-on experience and remains intent on pushing forward with TracSat.

“With over 35 years of experience, I want to challenge students by not giving them the answers, but instead giving them more questions to ask,” Dreessen says. “I’ve learned there’s more than one way to do something, and my way may not be the best way. I want to make sure they’re thinking about all the things that could go wrong, what has been overlooked, what hasn’t been accounted for. If you build a multi-million-dollar missile that should fly for 40 minutes but is obliterated after flying for only 30 seconds, leaving you with nothing, what do you do? I want them to ask questions and think beyond the lab environment to tackle real-world issues.”

That will be the continued goal of the program.

Dreessen is hoping Pikus will be the future connection with Purdue, though Dreessen certainly expects to be involved in some way moving forward.

Pikus, who will join GA-EMS in May, already has seen a keen interest among the students currently involved in the future of the project, whether they’ll continue with it personally or not.

“The mindset of students when we’re in this is not just always about how do we succeed in this project? A lot of people have been really interested in getting this testbed, making sure it’s very good for future projects,” Pikus says. “Some of them are seniors, so they may or may not be involved with it next year. But they still want to set this project up well for the future, so that’s an interesting mindset. People aren’t just concerned about what they’ll be involved in. They’re also saying, ‘We want to see this be successful in five years,’ when they might ever see this project again."