Redefining Flood Zones

Improvements in flood modeling will more accurately assess degree of risk

Flood risk determination in the United States needs far greater attention to the details, Purdue University researchers say.

Venkatesh Merwade, Professor of Civil Engineering with courtesy appointment in Agricultural and Biological Engineering, leads a research team that aims to improve flood modeling and prediction for the United States. The team seeks to accomplish this by finding ways to create better and more accurate information on flood prediction and risk, and by proposing methods for improving prediction by federal agencies.

Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) managed by Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) have been providing ongoing flood information to most of the communities in the U.S. over the past half century, Merwade said. However, the uncertainty associated with the modeling of FIRMs may adversely affect the reliability of flood predictions.

“Currently, the flood maps we use come from FEMA and many people buy flood insurance based on these maps,” Merwade said. “Areas are either inside the flood zone lines or they are out — and that determines whether or not one is required to buy flood insurance. These static maps have a lot of uncertainty to them.”

Civil engineering PhD student researcher Tao Huang is working on gaining a better understanding of flooding risk and implications to society.

“Risk is assessed by the probability of inundation,” Huang said. “It does not account for where people live. Right now, areas with no human population are being perceived as facing the same flooding consequences as cities with large populations.”

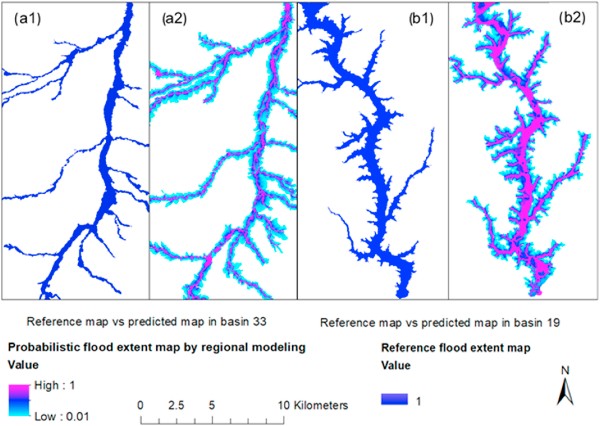

Merwade said a systematic understanding of the uncertainty in the modeling process of FIRMs is necessary. To resolve this uncertainty, Merwade’s research team has opted to the use Bayesian model averaging — a statistical approach that can combine estimations from multiple models and produce reliable probabilistic predictions.

“We cannot continue to base flood zones on lines on a map and a simple ‘it is either in or out’ approach,” Merwade said. “Your risk from floods increases and decreases greatly depending on how close you live to flood-prone areas. We need to account for the probabilities and determine the degrees of risk. Flood risk cannot be something as simplistic as whether or not you live on one side of a map line.”

Merwade said he expects to produce his findings in 2023.