Millers' Times

Millers' Times

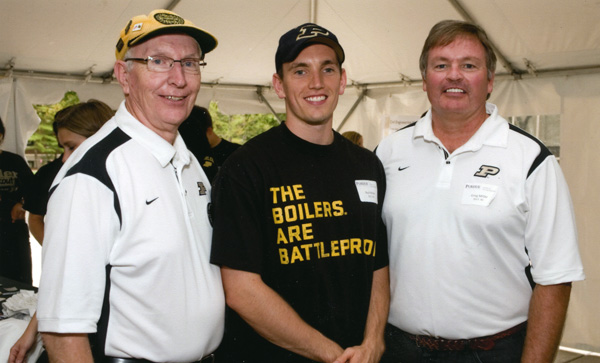

Three generations of one family share perspectives on Purdue civil engineering

By Gina Vozenilek

When he returned from summer camp one day, a young Nick Miller (BSCE ’08, MSCE ’09) opened his bedroom door to a big surprise. There were locomotives everywhere. In his absence, his parents Joan and Gregory Miller (BSCE ’80) had covered the space in Purdue Boilermaker Special wallpaper. The bathroom had been done up in a complementary pattern of gold pinstripe with slanted P. “It was great," the youngest Miller recalls. “It went very well with other Purdue decorations I already had in there.”

When the time came for him to start college, the handwriting, so to speak, was on the wall. “I didn’t apply anywhere else,” he says. “My heart was always set on Purdue.” And his mind was always on civil engineering, like his father and grandfather, Charles Miller (BSCE ’57) before him. The Millers represent three generations of proud Purdue civil engineering alumni.

A legacy begins

Charles was the first Miller man to attend Purdue. He was also the only one who did not dream of going there. A native of Elvaston, Illinois, he was planning to attend the University of Illinois with the rest of his buddies from high school when tragedy changed his course. Injured in an automobile accident that killed his father, he enrolled instead in a small college near home to recuperate. Six months later, while visiting family friends in Indiana, he was taken on a tour of Purdue’s campus. “That’s when I thought, ‘This is something different here.’ So I enrolled, and spent my last seven semesters at Purdue,” he says. “I just fell in love with it.”

Miller used his degree in civil engineering to take over the business his late father had started in 1946. Diamond Construction is a highway paving contractor in Quincy, specializing in hot-mix asphalt. “I worked all my life. From the time I was ten or 11, I started running the rollers and unloading railroad cars,” says Miller, who values his father’s lessons of responsibility and honesty. “I had a great father. He brought me up right.”

The hands-on appeal of civil engineering was evident to Miller from the beginning, whose fondest memories of his CE degree are based in Ross Camp, the now-defunct summer camp for teaching freshmen and sophomores how to survey. “It was my most enjoyable college experience,” he reports. “We lived in Army-style barracks and had a mess hall where we would do our paperwork at night—everything from computing and recording the day’s work to drawing topography maps and new road alignment coordinates.

“One night we set up our instruments outside and surveyed the stars to find true north. We were graded on all our experiences. After work in the afternoon, we would play league ball and swim in a pool that had been constructed several years earlier by a group of students. I was sorry to see the camp discontinued,” Miller says of the program that ended in 1960. “It taught working with a crew, each of them depending on and trusting each others’ work.”

The “crew concept” became very concrete for Charles and his wife Anna Mae. All three of their children became Boilermakers. Ann Marie majored in audiology and speech science, Scott in restaurant, hotel, and institutional management, and Gregory followed in his father’s footsteps. “We’re a Purdue family,” the eldest Miller says.

Middle Miller

Gregory Miller inherited his father’s work ethic, along with his company. He is now president of Diamond Construction, his position since his father’s 2001 retirement.

The second-generation Boilermaker applauds the civil engineering education he received in the late 1970s for its diverse subspecialty opportunities. By sophomore year, he chose construction from a list of areas, including geotechnical, materials, structures, and hydrology. “I liked the business concept that came with construction,” says Miller, who would go on to earn a master’s in construction management from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

He compares his experience in civil engineering with his father’s. While he missed out on the learning-by-doing that Ross Camp afforded the generations above him, he can compare notes with his son, who followed him. The later Millers experienced a different team-based, hands-on element of the civil engineering curriculum that is still a standard: the senior project.

Miller recalls some of the project details his team designed. “It was an Ivy Tech campus in Lafayette,” he says. “I, being the construction person, was in charge of contracts, site suitability, earth volumes, construction schedules, survey reports, and the final estimate.”

“I do remember getting grilled during the oral presentation by a professor sitting in the rear of the darkened conference room,” he recalls. “At the time, I thought, ‘Oh my, a hostile client. All I want to do is graduate in a couple of weeks.’”

Miller contends that the basic approach to problem solving that engineers are taught remains a constant. “Times haven’t really changed,” he says. “Engineers have always been good critical thinkers.”

Grandson makes three

Nick Miller, who graduated with his master’s in CE in December 2009, was introduced to civil engineering at an early age. Like his grandfather, he favored the hands-on nature of the discipline, preferring beams and columns to proton and neutrons. With his hands on a shovel and a hard hat on his head, the youngest Miller started out in the field, working summers at Diamond Construction.

Eventually he found himself in the front office, compiling bids and overseeing the aggregate composition in the quality control laboratory. “I liked the lab the best,” he says. “When I eventually took ‘CE 331,’ the class where you learn all the ASTM and standard tests, I had a leg up on the other students. I had already done it at Diamond.”

His interests are leading him in a direction away from the family business, although that possibility, his father and grandfather say, is always open to him. “My focus is structures,” says Miller, who wants to pursue a career in structural design. “I feel like that would be best utilizing what I have learned.”

As far as the changing times at Purdue, the youngest of the trio echoes a comment made by his grandfather, both of whom marvel at the display of Neil Armstrong’s slide rule in the A. A. Potter Engineering Center. “It just magnifies the accomplishments of those who went before us that much more,” he says.

One major shift in the education of a civil engineer is the increasing importance placed on environmentally sustainable practice. For his 2008 senior project, Miller and his team designed a Purdue Crew boathouse. “It was interesting to dive into a new code,” he says, referring to the professor’s emphasis on United States Green Building Council recommendations and requirements. The team incorporated recyclable materials, designed special parking spaces to accommodate carpool users, and added plenty of bike racks.

Miller also tells how engineers are actively recruited into the different schools after their freshman year, a trend intensified since the days his father was on campus. He estimates that the class size in civil engineering has roughly tripled in the classes coming up behind him. “Infrastructure development is being used as a way to jumpstart the economy,” he notes. “It’s a good time to be a civil engineer.”