Improving Worker Safety

Research aims to uncover how unsafe behavior compromises benefits of safety interventions among line workers

Transmission and distribution line workers face numerous on-the-job hazards every day. The risk of falls, electrical shocks, burns and other injuries is inherent in their work. Add to that long hours, working in adverse weather conditions and the expectation to work quickly to restore power to communities, and it is no wonder the occupation is frequently cited as one of America’s most dangerous jobs.

Despite numerous innovations in personal protective equipment (PPE) and improvements in safety technologies, injuries and fatalities persist. Could human behavior be a factor? Sogand Hasanzadeh, assistant professor of construction engineering in the Lyles School of Civil Engineering, is leading a study to determine to what degree an individual’s perception of risk influences their decisions in high-risk situations.

“By replicating different experimental conditions that simulate the job site while exposing workers to time-pressure and productivity demands, we can measure how different factors influence worker behavioral changes,” Hasanzadeh said.

Similar to how a thermostat activates the furnace or the air conditioner when the temperature deviates, risk compensation theorizes that humans adjust their behavior based on the perceived level of risk in a given situation. The amount of protective equipment a person is using could influence their assessment of risk.

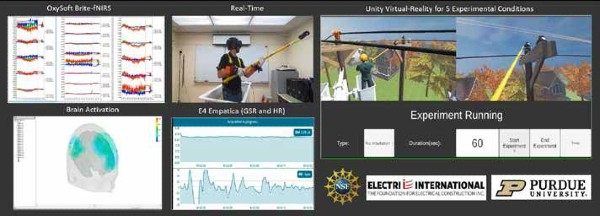

To test whether risk compensation exists among electrical contractors, Hasanzadeh and her team collaborated with the Purdue Envision Center to create a mixed reality environment that simulates a job site. The subjects, actual line workers, would stand in a utility bucket holding a hot stick used to move power lines while outfitted in their climbing gear and wearing a virtual reality (VR) headset.

The research team. From left: Kaylee Dillard, Aditya Mane, Sogand Hasanzadeh, Beyza Kiper, Makayla Simpson and Doug Hermo.

Participants physically use the real stick to complete simulated tasks in the VR environment, such as transferring live electrical wires from an old pole to a new pole in a suburban area. Various sensors measure psychophysiological and behavioral responses, such as eye movement, heart rate, emotional state, and brain activity. Should a subject get too close to a virtual power line during the experiment, they’d see and hear a loud electrical zapping noise, experiencing arc flash virtually.

“Each subject completes a set of tasks under five different experimental conditions,” Hasanzadeh said. “In each scenario, we manipulate different factors and monitor the changes in worker behavior. We’re measuring how an individual might compromise the benefits of safety interventions when they feel pressured to complete the task quickly. For example, we will incentivize them by giving them $5 if they finish a task within a certain time limit. The same thing happens on a job site, the more quickly they finish a task and move on to the next one, the more compensation they stand to earn.”

ELECTRI International, the foundation for electrical contractors, and the National Science Foundation funded the research. Hasanzadeh worked closely with industry advisors from Duke Energy and American Line Builders Chapter to build realistic scenarios that addressed the complex safety challenges related to electrical work. The researchers also assessed the level of risk aversion in each individual participant through a questionnaire that estimated propensity for risk based on personality traits and past behavior. The level of risk aversion was then correlated with the subject’s behavioral responses during the experiment.

Kaylee Dillard, a senior from Grand Rapids Michigan, assisted with the study. After learning about Hasanzadeh’s research focus, Dillard applied for a spot on the research team. As a construction management major, Dillard was particularly interested in learning more about how human behavior contributes to a safe environment.

“You have to be a people person in construction management,” Dillard said. “To be an effective project engineer or project manager, you have to be able to communicate with others. To understand the different hazards your crew faces, it’s important to look beyond technology and construction. Psychology plays a role in safety, too.”

Kaylee Dillard and Aditya Mane place the VR headset on a research subject.

Dillard knew she wanted to pursue engineering and chose to attend Purdue because it offered a Big Ten experience in a collegial, close-knit environment. The opportunity to assist with a major research project as an undergraduate enhanced her academic education, and gaining experience working with VR technology boosted her career prospects. For the experiment, Dillard facilitated orientation for subjects to help them understand the purpose of the research before applying fNIRS, sensors placed on the head to measure brain activity.

“Undergraduate research opportunities in my major are rare,” Dillard said. “Learning how to conduct experiments through VR and how data is collected with fNIRS is really going to help me in the future. The construction industry changes very fast and the integration of technology is increasing. This experience will definitely help me with future employers.”

Graduate researcher Aditya Mane (MS CE’20) mentored the team of three undergraduates on the research project. Along with Hasanzadeh, he was present for every experiment and monitored the computer systems collecting data from the subjects.

“Undergraduates have less exposure to research and may not understand how to enforce the parameters of an experiment,” Mane said. “My main responsibility was to introduce the undergraduates to research and help them understand the protocols. This project was a good start that they will build upon.”

In addition to ensuring the sensors were functioning properly and collecting data, Mane also monitored the subjects’ heartbeats, temperature and respiratory reactions to ensure they were not over-exerting themselves during the experiment.

“We gave them breaks between scenarios so the participants could relax and calm down,” Mane said. “We didn’t want elevated body responses to interfere with the data collection during the next phase of the experiment.”

Graduate student Aditya Mane assists a research subject with safety gloves worn by line workers.

Like Dillard, Mane was excited to assist with cutting-edge research.

“Focusing on human subjects is relatively new in the construction industry,” Mane said. “The design of this experiment involved physical activity coupled with virtual reality — that’s very different from the types of research projects that have been conducted before. The most interesting part for me is that you can refine processes and reduce errors to increase safety, but you cannot change the individual’s behavior. You must analyze and understand how people react in order to mitigate safety hazards.”

The influence of human behavior on safety conditions was something Mane witnessed firsthand on construction sites in his native India.

“While working on construction sites, I personally observed how human error can put others in danger,” Mane said. “A job site can quickly become unsafe because of one person’s state of mind. Transmission line workers are subject to the same life stressors and external pressures as any other occupation. The difference is, their job requires them to work under already dangerous conditions and someone who is distracted or carrying a large mental load might behave in an unsafe manner. In this case, that can have fatal consequences.”

The researchers used a few different techniques to simulate increased mental loads, such as a fan blowing on the subject to add an environmental stimulant or giving subjects a secondary task to complete while setting a time limit on correctly performing a task and offering a monetary incentive to complete the task on time.

“All three things going on at the same time, the pressure of a time limit, the opportunity to earn more money and the need to memorize a sequence of numbers, simulates the stress of normal life,” Mane said. “The experiment was designed to replicate the same conditions line workers encounter performing their jobs every day.”

The research is ongoing, so no hard conclusions can be drawn yet. But Hasanzadeh is excited about the possibility of positively impacting industry safety.

“I’m very passionate about people,” she said. “I don’t like viewing workers as passive recipients of safety interventions or technological advances. I want to engage workers as proactive agents who will inform the design and implementation of more effective interventions. It’s not an issue of more training. It’s about how the worker thinks, perceives risk and makes decisions at job sites.”

While conducting the mixed-reality experiment, researchers reference a dashboard that displays various data.