Research

|

|

|

Our Questions

Below are some basic scientific questions that we are pursuing. You can find our previous work related to each in the publications page.

How does the brain analyze a pressure signal to give us a mental picture of the different sound sources that make up the scene?

The nervous system is incredibly successful in solving staggeringly difficult problem that are currently beyond the capabilities of machines. Many of us could talk to a friend at a noisy restaurant from across the table. Instead of you, if it was your smartphone's voice-based assistant in your seat, what do you think your friend's experience would be?

To see why listening in a complex environment with many sound sources may be difficult, imagine being blindfolded and ears plugged, and standing on the shore of a lake where there are multiple boats in the water. Now imagine sticking just one or two fingers into the water surface and being able to observe nothing other than the ripple pattern that hits your fingers. From just this information, being able to infer what objects are in the lake, and what each is doing seems insurmountably difficult. Yet, amazingly, this is exactly what the auditory system routinely achieves by just analyzing the sound, i.e., ripples in the air that reach our ears. At SNAPlab, we attempt to understand the mechanisms by which the auditory system achieves listening in complex scenarios such as those with multiple sources of sound.

In addition to understanding how the brain interprets sound signals to analyze the scene surrounding us, a prominent focus of the lab is to understand how this process will be affected in sensorineural hearing loss and aging.

Why do some listeners experience difficulty communicating in complex/noisy environments?

Millions of individuals, both children and adults, experience difficulty listening in noisy environments even when they are able to communicate easily in quiet one-on-one conversations. This includes people with sensorineural hearing loss, older listeners, those with autism spectrum disorders, or sometimes even without any known cause (in which case, clinically, they are grouped under the spectrum known as central auditory processing disorders). Even among those with no hearing complaints, we have shown that large differences exist in the ability to perceive subtle features of sounds and to listen in multisource environments. Understanding the nature of hearing difficulties, and individual differences in perceptual ability is a focus of SNAPlab.

How does exposure to loud sounds alter the auditory system, and in turn affect perception in complex environments?

There is evidence from animal studies and suggestions from our previous human work, that overexposure to noise could alter the physiology of the auditory system even when not inducing clinical hearing loss. A current focus of our lab is to characterize these changes systematically from the cochlea to the cortex and how it affects one's listening ability in complex multisource environments.

How does early aging alter the auditory system, and in turn, affect perception in complex environments?

Similar to our studies on noise exposure, based on evidence from animal data and our previous work, another current project is to understand the effects of early aging (i.e., before clinical hearing loss is manifest) on the auditory system.

How does the "central" auditory system change in response to changes in the periphery?

The nervous system is known to adapt in many ways to changes in the statistics of the inputs it receives. A possible source of such change is the alteration in cochlear or auditory nerve responses (owing to noise-induced hearing loss or aging) that act as inputs to the brain. We are interested in understanding how the rest of the auditory system adapts to such changes in the periphery, and what consequences that might have for perception. In addition, such changes can affect how we interpret many of the non-invasive measures of auditory function that can be obtained from humans -- We are also interested in understanding these effects.

How do we selectively listen to one source of sound in a crowd while ignoring others?

Our ability to selectively attend to the sound source of interest in a mixture and ignore other sounds is well known but not well understood. At SNAPlab, we study the neural mechanisms that support such auditory selective attention.

Translational Goals

Though we often engage in basic scientific research, the overarching goal is to help translate the knowledge to effective clinical and engineering tools. The basic questions asked, and the non-invasive measurement techniques used, naturally lend themselves to translational research towards:

- Biomarkers for the diagnosis and (importantly) stratification of listening problems owing to various causes (e.g., noise-induced hearing damage, central auditory processing disorders, aging, autism)

- Devices to assist patients with hearing difficulties

- Decoding brain signals for brain-computer interfaces (BCI)

- Mimicking biological auditory computations in machines for various technological applications.

Techniques

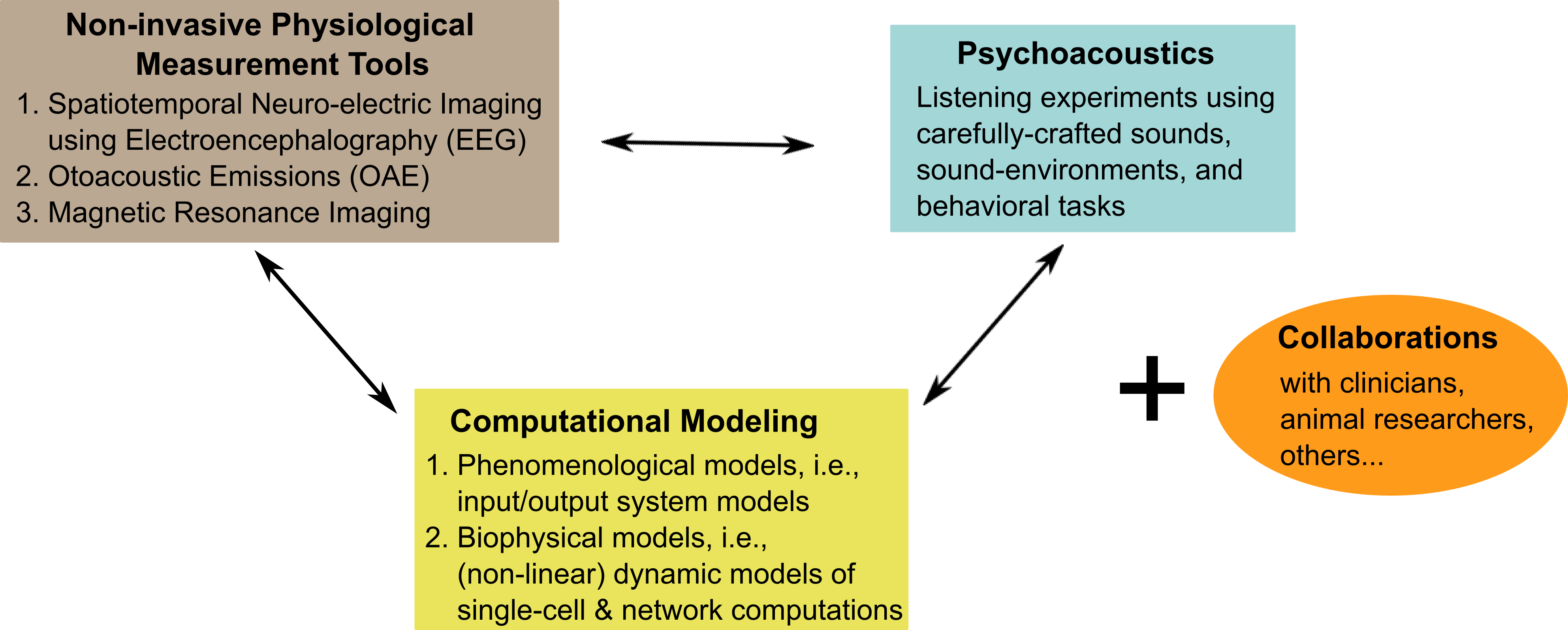

The complexity of the neural computations that underlie auditory perception demands a detailed multidisciplinary approach to its study. Thus we employ several approaches in conjunction with each other. Given that the phenomenon we are interested in studying is human perception, we conduct experiments to understand the relationship between with sound information and the corresponding percept, under different behavioral task conditions (a.k.a. Psychoacoustics). To probe the neural mechanisms that support such perceptual outcomes, we us a range of human neuroimaging and electrophysiological techniques to directly measure physiological responses to sound. We analyze these responses using signal processing, statistics, machine learning approaches. The knowledge gained from psychoacoustics and objective physiological measures is then integrated into computational models of audition, which then inform the next set of experiments. We also take advantage of the large and vibrant hearing-research and clinical communities at Purdue and IU through active collaborations.