Epic partnerships Engineering Projects in Community Service celebrates 20 years of connecting engineering and community.

Epic partnerships

| Author: | William Meiners |

|---|---|

| Subtitle: | Engineering Projects in Community Service celebrates 20 years of connecting engineering and community. |

| Magazine Section: | Engagement |

| Article Type: | Feature |

| Feature Intro: | The Global Alternative Power Solutions (GAPS) team is developing alternative energy solutions to provide power to remote villages in rural Colombia through collaborations with Colombian universities, communities and industries. (Photo by Christine Benner) |

| Feature CSS: | background-position: 100% 10%; |

Engineering Projects in Community Service, or EPICS, has been connecting Purdue and communities for two decades. In that time, Purdue student teams have shared their developing engineering expertise to meet the needs of scores of community organizations ranging from local agencies, such as the United Way, to remote South American villages.

Jamieson, the John A. Edwardson Dean of the College of Engineering and one of the program’s founders, believes the projects are mutually beneficial for community partners and students. That core principle has driven some 400 projects of various sizes and differing scopes during those 20 years. EPICS teams have developed educational materials for the Columbian Park Zoo in Lafayette, Indiana, and collaborated with Colombian universities and industries to bring alternative energies to remote South American villages.

The teamwork, multidisciplinary by its very design, prepares students through client interactions and adaptive solutions for jobs in a variety of fields. And Jamieson frequently hears from Purdue alums who speak passionately of their own days in EPICS and its influence on their careers.

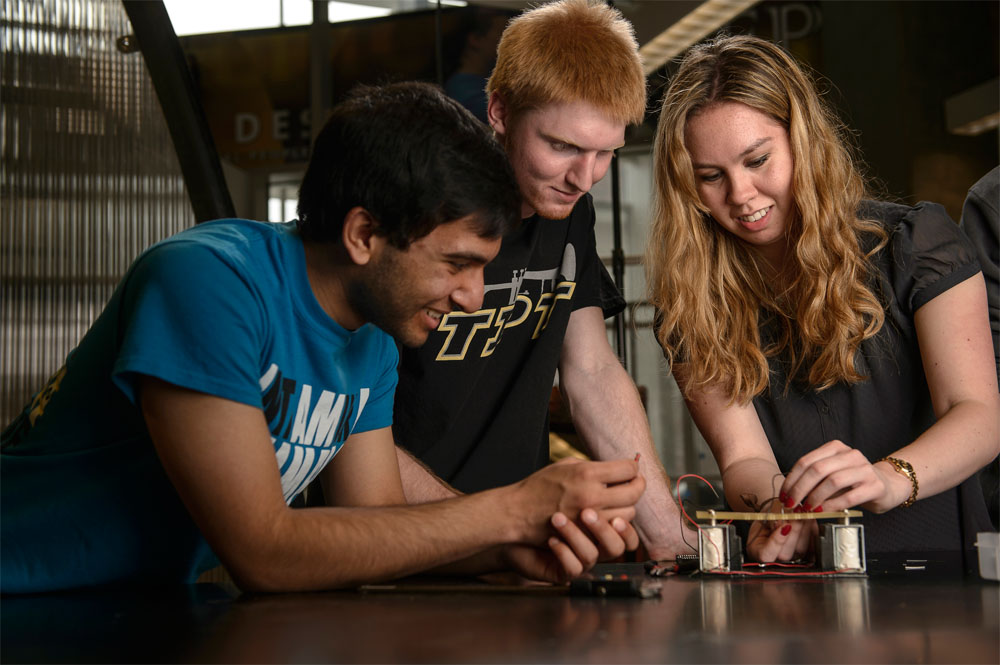

(Photo by Steven Yang)

Technical content in greater context

Jamieson says EPICS was born out of an increasingly vocal call, nationwide, for engineering graduates to have communication skills that could match their technical abilities and training. Typically, young engineering graduates didn’t know about teams or customer awareness, and they seemed to have little grounding or context for their work.

A group of faculty from the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, led by Jamieson and Ed Coyle, a former professor of electrical and computer engineering, talked about finding multi-semester projects that would enhance classroom learning. “The projects would provide a context in a bigger thread,” Jamieson says. “Serving a customer would also complement their traditional technical skills as they design something to meet that customer’s requirements.”

Allowing engineering students, not yet full-fledged design engineers, the opportunity to work on significant projects seemed like a good idea simply waiting for the perfect outlet. Jamieson says the light bulb moment occurred when we learned of the U.S. Department of Education’s Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education to encourage initiatives that would connect students with their communities. That first grant proved to be the conduit to conversations with the United Way of Greater Lafayette.

“On their side, it was clear that engineering expertise absolutely has a role in human service agencies. Engineering consultants, however, can be expensive.” Jamieson says. “Suddenly we had this symmetry of students who needed professional skills that go beyond the technical material they’re learning in class and community organizations needing affordable access to engineering and technology solutions.”

Those early years provided learning opportunities not just for students, but also for the architects of EPICS. They experimented with team dynamics and the various roles of team leaders, and they considered how best to maintain projects that do not end with a particular semester.

Jamieson likens the ongoing nature of the projects to a sports team with seniors graduating and new students replacing them. In addition to the professionalism and communication skills students gain, writing skills became critical to document projects from one semester to the next.

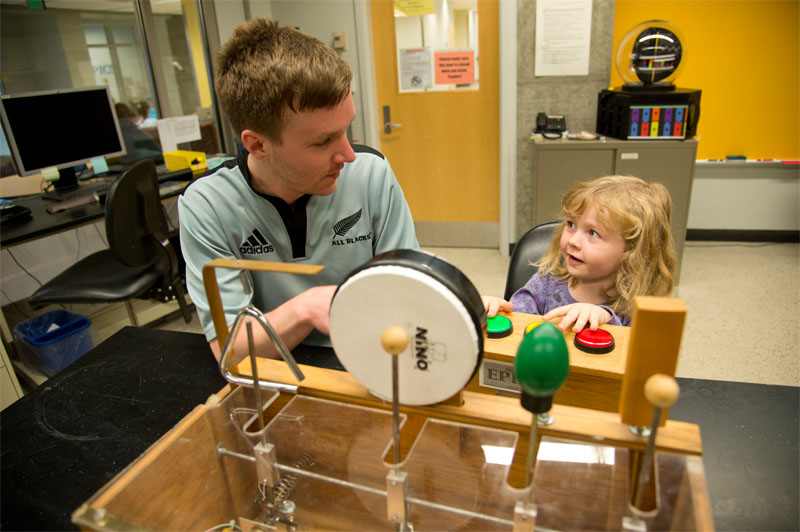

(Photo by Suzanne Walker)

Two-way impact

The service and service-learning components that made EPICS successful 20 years ago still hold true today. “As a land-grant institution, it’s really critical that we have impact within the local community and that we’re serving Indiana,” says Darryl Dickerson, associate director of the Minority Engineering Program and EPICS advisor. “More broadly, EPICS allows people in the community to see what engineers can do and make the connections that this is what engineering is all about.”

For Erin Groll, a sophomore in industrial engineering, the opportunity to build something for the community might be the very thing that called her to engineering in the first place. Growing up in West Lafayette, she attended various Women in Engineering programs. She looked at engineering programs all over the Big Ten and as far as the East Coast, but decided Purdue provided the best fit.

Through her first three semesters on campus, Groll has worked with the same EPICS team at the Imagination Station in downtown Lafayette. “We build exhibits for smaller, not-for-profit children’s museums around the state,” she says. “We have two projects right now — a laser harp and a Mars rover.”

As a first-year engineering student, Groll served as the project partner liaison between the client and the technical team, making sure they were building the harp to the client’s specifications and including them in the design review process. This year she’s the project manager for both exhibits in the works.

Students also extend their technical foundation in addressing project challenges. Groll says the team has worked through several issues with the laser harp — from smoothing out soldering issues that affected the electronics to making sure the drilled holes are correctly lined up to allow the lasers to play notes on the sensor board. “There’s a lot of problem solving in overcoming things to make sure we’re building it correctly.”

And whether teams are working on interactive educational pieces, environmental projects, or innovative devices that enhance life for children with disabilities, the students begin to develop the professionalism and ethics that go along with engineering aptitude. They’re learning on the fly through projects that mirror the real-world responsibilities they’ll face in the future.

“Students are able to see immediately the impact they can have with their technical skills,” Dickerson says. “And that draws in students from all different backgrounds.”

In her role as the project liaison, Groll says EPICS has helped sharpen her focus on client needs. “It made me think about the other side because that’s not something you normally see in an engineering class, where you might think about the problem and turn in a paper or prototype,” she says. “In EPICS you learn that you’re not building something for yourself, but for someone else.”

Beyond expectations

Bill Oakes (PhD ’92) returned to Purdue in 1998 to join the faculty of what was then the Department of Freshman Engineering. Asked to teach an EPICS class that would bring first-year engineering students to the design table, Oakes knew his own industry experience could help inspire his students’ projects at the Imagination Station and in their work for Habitat for Humanity. Named the EPICS director before the end of that first year, Oakes remains in the position, now working alongside co-director Carla Zoltowski.

The logistical concerns in those early days included how best to include the first-year students, as well as how to scale the program up and promote it across campus as an interdisciplinary option. Oakes says some of those lessons laid the groundwork for today’s EPICS learning community. Groll is among the 120 students, about 70 percent of whom live in the same residence hall, who take a common first-year class while joining EPICS teams with sophomores, juniors, and seniors.

Working on an evolutionary educational model, however, may have excited Oakes the most. “The EPICS students were actually operating more like professionals than students,” he says. “The key is that you’re engaging students in an authentic experience where they need to interact with others. It forces them to use more than just the knowledge they’ve acquired in their courses.”

The subsequent years have been a ride that Oakes could not have imagined. “We do workshops and have collaborations on six continents. We have 25 active universities in the consortium, and there are about a dozen more in the process of putting EPICS into their curriculums,” he says. “Within the engineering education profession, EPICS has helped move community engagement into more of the mainstream. It’s been a privilege and joy to be part of that.”

For the program, which never has stood still, Oakes foresees more collaborations with other universities, especially on the global scale. He also sees greater inroads into K-12 programs. “We’re in just over 100 schools in 16 states,” he says. “I think we will be in thousands of schools at some point.”

Building upon a good idea is not just about coming up with better practices. While becoming an international model, the program has looked continuously at learning and community outcomes. And participants’ enthusiasm has been matched by great support. Beginning with that first grant from the Department of Education, EPICS has garnered major awards from the Carnegie Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the American Society for Engineering Education, and more. To date, the program has been supported by more than $5.1 million in federal grants and $5.5 million in corporate and alumni gifts.

As for the 20-year reflection, Jamieson is sure to hear from more EPICS alums at celebratory events, though she may be proudest that the initiative helped put Purdue above the learning curve. Around the year 2000, accreditation issues began to focus on expectations of communication, teams, professional context and ethics. “We were thrilled about the proposed change in what engineering students needed,” she says. “With EPICS, we were already doing it.”