Motorola Solutions Foundation- and Ecolab Foundation-sponsored field trip takes Chicago high school students to the heart of EPICS at Purdue

Elena Avila ran to share the good news.

Proof her device worked was in a cup in her hands: Drinking water from the high school drinking fountain,free of lead that had been there minutes before.

Thanks to the filter she created in an EPICS class at Chicago’s Amundsen High School, one over 100 K-12 partners with EPICS at Purdue.

For a career Avila thought was “building stuff,” she had fun as an engineer for the two-month high school class.

“I got to pick something I was passionate about and collaborate with a team to make it real,” said Avila, a senior. “There’s a creative side to (engineering), and I really enjoyed the fulfillment of making something that works.”

That was exactly why teacher Aleks Rusic wanted his students to see EPICS at Purdue: to get inspiration from the creative, innovative and fun side of engineering. The experience could inspire an engineering future, right at the heart of EPICS.

Rusic and 50 high school students ventured from Chicago to the Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering at Purdue University on Oct. 28. Students participated in a tour of engineering buildings, a session with the Office of Future Engineers and worked with active EPICS at Purdue projects. Amundsen High School’s visit to West Lafayette's labs was funded by Motorola Solutions Foundation and Ecolab, longtime partners of EPICS at Purdue.

“I think a lot of students have this narrow image of engineering, that it’s just math,” Rusic said. “My goal through (touring Purdue) was to introduce them to different aspects of engineering. I wanted to show (the students) how many options they have, and I hope it motivates them to feel confident in pursuing engineering in the future.”

The first EPICS-based course at Amundsen, launched in 2017, focused on tools and building essentials. Students experienced the fundamentals of making sturdy and successful prototypes, including tool usage and workshop safety. Four years later, Rusic added a section about programming electronics. It introduced students to microcontrollers, soldering and using motors and sensors.

EPICS at Amundsen employs the core tenants of EPICS with a condensed timeline. Amundsen students find stakeholders, design, build and present a project in two months.

Charlie Marsh’s stakeholders were road-sharing electric cars and cyclists. His team’s EPICS prototype was a mounted sensor. Whenever a car comes close to the sensor, an alarm sounds to alert the cyclist.

It was a win-win: Cyclists would be safe from oncoming cars, and cars didn't need to have loud engines to be perceived.

Seeing college students working with similar stakeholders during the visit to Purdue cemented Marsh's passion for creation.

“I know I want to do engineering, and I want to do it at Purdue,” Marsh said. “I like building things and using practical knowledge to combine everything into something with results. I thought EPICS was a good pathway for me and a good way to show off and develop my skills.”

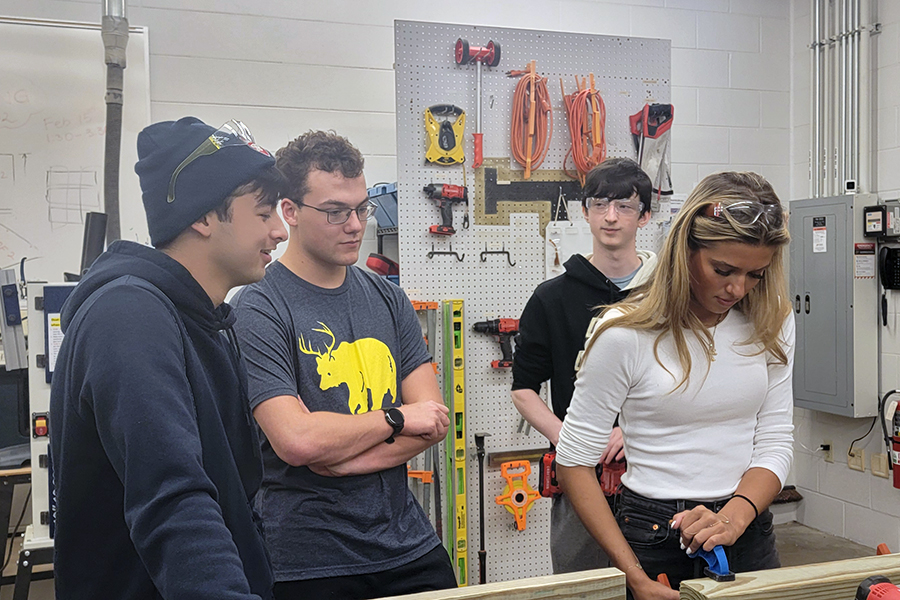

Marsh, a senior in his second year of EPICS, originally thought about pursuing civil engineering. After seeing EPICS in action at Purdue, he began considering other engineering disciplines. Amundsen High students sat in on Week 10 of the EPICS course, meaning Purdue teams were building physical prototypes.

“Seeing things come together is kind of exciting, isn't it?” Marsh said.“It’s like a big puzzle: You see everything come together at the end. I’d never seen that before in an actual project that makes a difference (before EPICS). It makes me want to do that in the future.”

For Amundsen senior Harrison Schwartz, being in West Lafayette was the culmination of two surprising years in EPICS.

As part of a career program, Schwartz enrolled in the EPICS course. He thought it was going to be a community service class. By the end of the first week, Schwartz knew that EPICS actually involved engineering, problem solving, coding, building and presenting.

It quickly became his favorite course.

“(Engineering) requires so much thinking and being a creative person,” Schwartz said. “It’s helped me develop critical thinking skills and creativity so much. And then presenting what we’vecreated, making sure you sound good, was so important.”

Schwartz and his team built a button-lock mechanism to put over a knife block. Over 150,000 injuries with knives are recorded annually, he said. To prevent more injuries — especially in small children handling knives unattended — the team made a childproof lock that required both hands to open.

“Making the prototype was hard,” Schwartz said. “There were so many moving parts we had to make sure worked. Right before we presented, we were pressing the buttons over and over to make sure it was still working.”

Creating his own device through EPICS augmented Schwartz’s interest in Purdue engineering. He is excited by the prospect of immersing his education in practical application with positive, community-bettering impact.

“Research indicates that the earlier you expose students to STEM concepts, the more likely they are to pursue a STEM degree and career,” assistant director of high school programs Charese Williams said. “The EPICS K12 program offers the opportunity for both middle and high school students to begin to understand that applying skills learned in the classroom can be used for the betterment of their community. EPICS offers a structured way for them to improve the neighborhood in which they live.”