A new type of miniature propulsion system was tested aboard Blue Origin’s New Shepard NS-29 mission in February 2025 — the culmination of a dozen years of development. The lightweight and environmentally friendly thruster, co-developed by Purdue and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, could make low-cost miniature satellites more reliable and versatile.

The actual device, called the Film-Evaporated MEMS Tunable Array (FEMTA), is smaller than a penny, needs minimal electrical power and uses only ultra-pure water as a propellant.

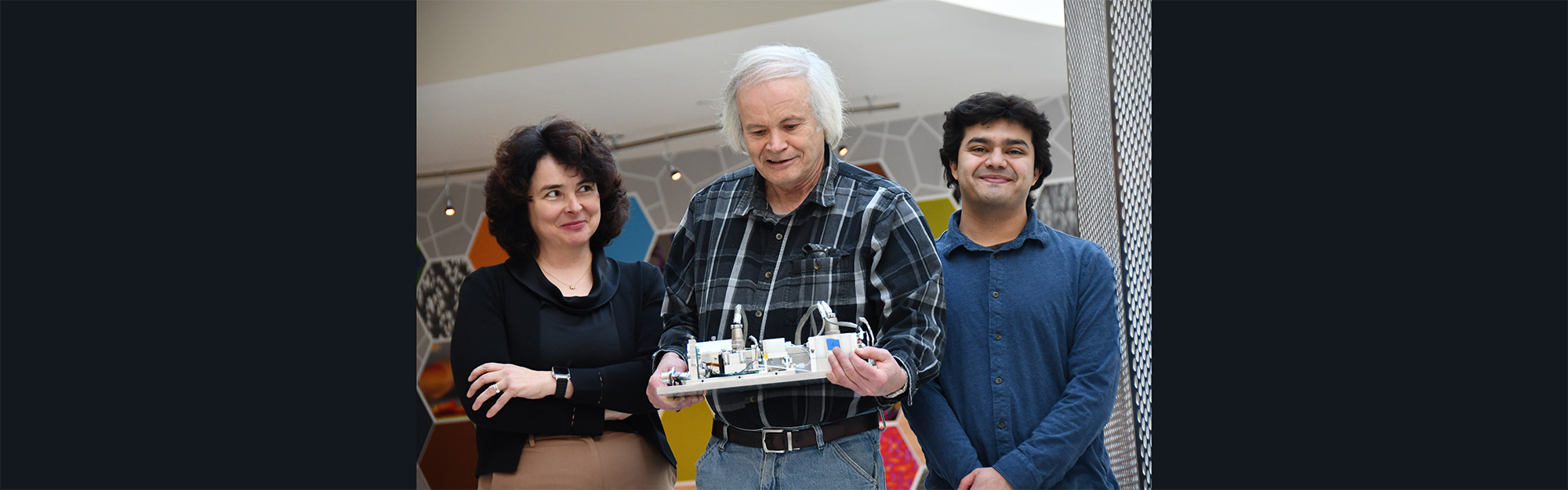

More than 100 students, including graduates and undergraduates, have been involved in the project, says Alina Alexeenko, a professor of aeronautics and astronautics. She has led this project with her co-principal investigators, AAE professors Steve Heister (now emeritus) and Steven Collicott.

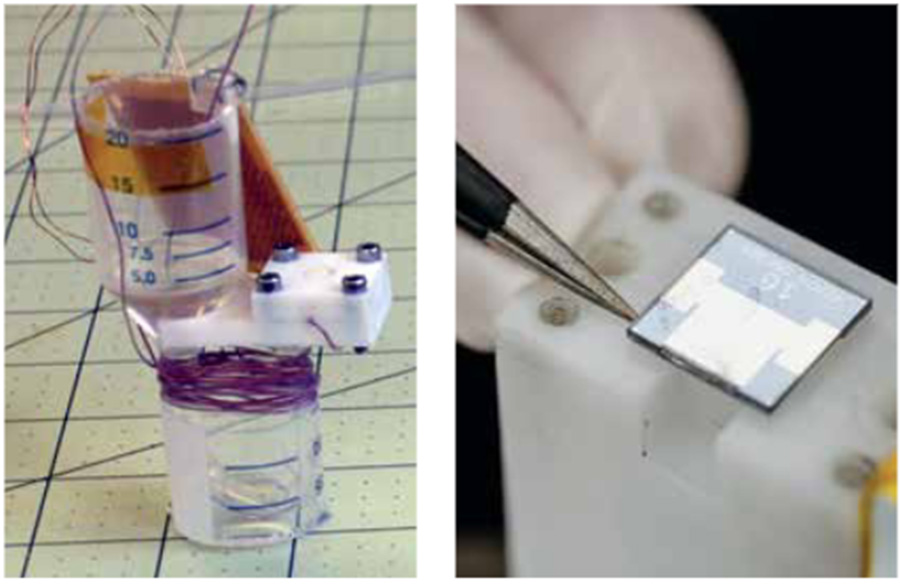

“We started with a very rough, scrappy prototype, made from a plastic syringe bought in a pharmacy. Then we got funding to build our first MEMS [Micro-Electro-Mechanical System] device, and then tested hundreds of them to get a working integrated micropropulsion system that can turn a CubeSat, and so on from there.”

The first proof-of-concept MEMS device, built in 2013, used parts of plastic syringes purchased at a farm supply store. After a dozen years and many iterations, the research team would eventually use the high-tech micromanufacturing tools in Purdue labs to make the FEMTA thruster ready for flight testing.

The project was a constant progression, supported by $1.5 million in consecutive grants from NASA and the Air Force. It has resulted in several patents and four doctoral dissertations. Those results, Alexeenko says, are a bargain: “In the space industry, it would take a lot more to get a propulsion technology from TRL 2 [NASA Technology Readiness Level 2] to spaceflight. FEMTA is now on the map of available space-tested smallsat propulsion technologies.”

Over the past decade, thousands of small CubeSats have been launched into low earth orbit to perform a variety of tasks — from providing internet service to monitoring soil moisture on Earth. CubeSat sizes range from “one unit” (1U), measuring about 4 inches per side, extending up to 1.5, 2, 3, 6, and even 12U.

Alexeenko says CubeSats make space missions much more cost-effective. “They offer an opportu-nity for missions such as swarm and constellation flying, that their larger counterparts cannot eco-nomically achieve.”

But, being so small, there are few practical ways to move them around during flight. That makes CubeSat missions more likely to end early from just being disoriented. To achieve their full potential, CubeSats will require micropropulsion devices to deliver precise low-thrust “impulse bits” for scientific, commercial and military space applications.

Existing options aren’t very practical, says Tony Cofer (BSAAE ’09, MSAAE ’10, PhD AAE ’15), a spacecraft laboratory engineer in AAE. He earned his PhD while working on this challenge and holds two patents related to the FEMTA thruster. “CubeSats currently have very limited propulsion options because those options are so bulky and expensive. A butane gas system can cost around $300,000, and it takes up half of a U [CubeSat Unit]. So, generally, you drop them into orbit and hope for the best. Most of them use reaction wheels and magnet torquers for attitude control, but both can be kind of jittery,” Cofer says.

Inspired by inkjet printers, which use tiny heaters to propel droplets of ink, Cofer was able to develop a tiny thruster that would shoot out super-purified water to propel a satellite. The thruster opening is only 10 micrometers wide — a critical design feature. At this size, surface tension of the water keeps it from flowing out, even in the vacuum of space.

Activating small heaters at the thruster nozzle creates water vapor and provides a tiny amount of thrust. "It’s about as much force as an eyelash falling on your hand,” Cofer says. “But these things scale up. They weigh less than a tenth of a gram, and you can put together a bunch of them and get 200 to 300 µN per watt of power."

A small tank of ultra-purified water serves as propellant. Water is much safer to handle than hydrazine, a dangerous rocket propellant that is widely used for maneuvering spacecraft.

Dr. Tony Cofer working on the FEMTA thruster with students.

And the electricity requirement is very small. In a paper published in 2017, Purdue students demonstrated a thrust-to-power ratio of 230 micronewtons per watt for a specific impulse of 80 seconds. “This is a very low amount of power,” Alexeenko says. “One 180-degree rotation can be performed in less than a minute and requires less than a quarter watt, showing that FEMTA is a viable method for attitude control of CubeSats.”

The device, Alexeenko says, can also be used to do space science. By providing a source of water under extreme atmospheric conditions, like on the surface of an asteroid, the FEMTA can be used to test hypotheses about the origins of life on Earth.

The original thruster design was developed under a University SmallSat Technology Partnership grant from NASA and a NASA REDDI grant provided the funding for the launch and some development costs. “The team at Goddard, including Eric Cardiff, Khary Parker, Carl Kotecki and Manuel Balvin, gave us advice and guidance throughout the design process,” says Steve Pugia (BSAAE ’18, MSAAE ’20), a PhD student at Purdue. Pugia worked on the flighttested iteration and has been doing data analysis since the thruster returned to Earth.

“Goddard had a lot of input in the different generations of the thruster, like with making the smaller capillaries so we didn’t need a closing shutter mechanism to prevent background evaporation,” he says.

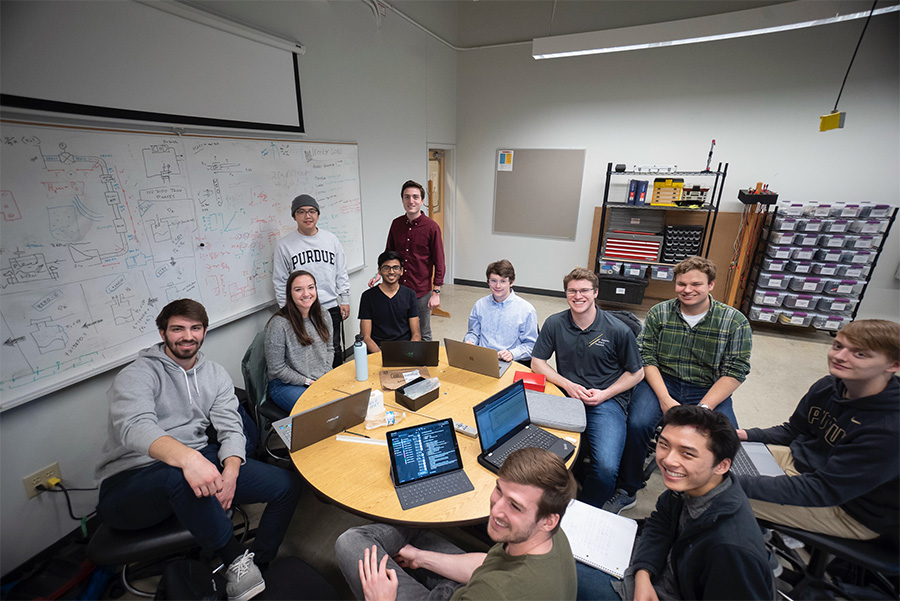

In recent years, the project has been run within a Vertically Integrated Projects course at Purdue. VIP is a cornerstone of the hands-on experience that makes a Purdue education so valuable. Kate Fowee Gasaway (BSAAE ’16, MSAAE ’18, PhD AAE ’22), who co-authored the 2017 research paper on FEMTA, now works with CubeSats at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Sessions of Purdue’s Vertically Integrated Projects course, like this group from Spring 2020, brought in dozens of student collaborators at a time to bring this concept to flight-readiness.

PhD student Jesus Adrian Meza Galvan, a teaching assistant for the FEMTA VIP course, chose Purdue precisely for this opportunity. He’s also grateful to sometimes talk with Gasaway about the craft of teaching.

“Many schools have strong aerospace programs, but not many offer hands-on opportunities with space-flight projects like Purdue does. I chose Purdue specifically because it has a strong focus on experimentation,” he says.

Galvan and Pugia accompanied the device to the Blue Origin launch site in Texas and saw it loaded onto the rocket booster. This flight opportunity will test the device in the rigorous environment of space.“I was looking for a project that would utilize my skills in microfabrication while also expanding my experience developing space hardware,” Galvan says. “FEMTA fit both of those things perfectly and I was lucky enough that Dr. Alexeenko offered me the chance to work on it.”Galvan believes the VIP program is a great opportunity for undergraduate students to get hands-on experience early in their education.

“All together the project has had contributions from more than 100 undergraduates,” he says. “We have had students from all disciplines be involved as early as their first semester as freshmen and carry on until their graduation. I think having that level of exposure is very rare.”

AAE Professor Alina Alexeenko, Blue Origin Mission Manager Laki Vlachos, and PhD student Jesus Adrian Meza Galvan attended the launch of Blue Origin’s New Shepard NS-29 mission in February 2025.