EPICS consortium supports community-minded engineering efforts worldwide

Founded in 1995, EPICS revolutionized hands-on learning for engineering students at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. The program changed students’ experiences so positively that other universities began to take notice.

How could they bring EPICS to engineering students?

Ed Coyle, an electrical and computer engineering professor at Purdue in the 1990s and a co-founder of Purdue's EPICS, won a National Science Foundation grant to help with dissemination of a national program. Notre Dame and Iowa State were the first universities on board, former EPICS director William Oakes said.

Oakes led workshops at American Society for Engineering Education conferences and at individual universities about how to start an EPICS program, and interest continued to increase.

As of December 2025, over 40 institutions across five countries have adopted the EPICS model, which became the university consortium.

"We've come up with something that is good for the students, good for the community, and it's the right thing to do," Oakes said of how persistent Purdue has been to share its EPICS model.

The EPICS program's application across each university varies from a course to a full program, tailored to fit an institution’s needs and capabilities. Established programs are guided by three core values of the EPICS at Purdue service-learning program: Students earn academic credit for participating in a team-based engineering design project; the project provides a service to community organizations through partnership; and each program supports reciprocal partnerships with community partners and with other partners in the EPICS consortium.

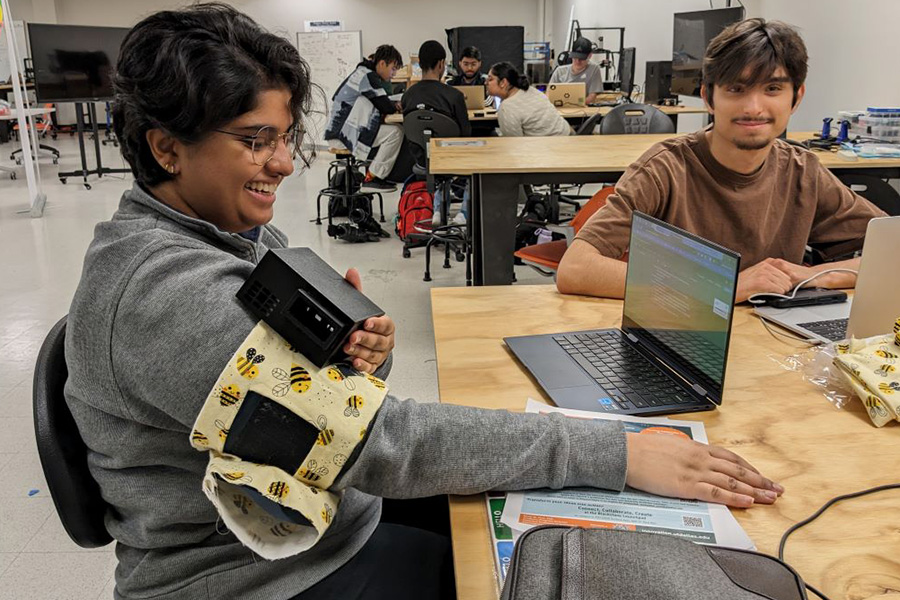

UT Dallas: Expanding service to all students

Andrea Turcatti’s proposal would add a lot.

She knew that when she walked into the Dean of Engineering’s office at the University of Texas at Dallas (UTD) to propose a new experiential learning program.

And it was going to involve EPICS at Purdue. It had to, actually. Turcatti’s resources, curriculum suggestions and model of execution were Purdue’s program.

Turcatti’s experiences with EPICS followed her to UTD, even though she never worked directly within the program. For nine years at Purdue as director of instructional labs, she was a colleague of Oakes. She regularly listened to excitement about EPICS, and it affected her.

“I really have a passion for the program,” Turcatti said. “I saw the possibility and great opportunity to do the same thing."

Turcatti moved to UTD in 2010 and reconnected with EPICS in 2014. The university Consortium was perfect for keeping up to date on EPICS news, as it’s a network of the over 40 universities that have adopted or adapted the program to their curriculum. The consortium enables university staff to contact Purdue — and other universities with the consortium — for collaboration, information, networking and support.

A consortium workshop gave Turcatti the resources and confidence she needed to propose the new experiential learning program. First, students had the engineering theory, she argued, but they needed the hands-on practice as early as they could get it. EPICS could give that to them.

“Making an impact on the community isn’t just for seniors,” Turcatti said. “It’s for everybody.”

Turcatti would know. As the director of UTDesign Students and Engagement, her primary role is providing students with a well-rounded learning experience that sets them up for success. She saw the end results of those partnerships as a course design reviewer at UTD, just like she had known at Purdue. The teams did so much work and delivered promising prototypes.

If students had time to work on a project, from beginning ideas to final product, Turcatti marveled at all the groundbreaking discoveries student design experiences could lead to.

Turcatti’s proposal worked.

With the Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science as a partner, the first EPICS course at UTD was January 2016.

The first course had 24 students spread throughout five projects. Students met in the lab twice weekly and would frequently check in with Turcatti about project progress. One early project (2018) was paring down and shaping up three separate databases into one usable system for Trusted World, a nonprofit with the sole mission of connecting nonprofits and community centers through a coordinated inventory platform.

Within three years — or more, as Trusted World has been a longstanding partner of EPICS at UTD — EPICS at UTD students presented an inventory management system web app. The system not only kept track of available resources, but what was ordered by constituents. The system proved successful: Resources flew off the shelves in north Texas in the wake of the 2019 hurricane season. Trusted World has been a consistent partner ever since.

The consortium has been a regular source of ideas, support and insightful answers to Turcatti’s questions as the program grew. When she has questions about improving the UTD program, Purdue staff are the first ones she asks.

“This is a great opportunity for our students to work on real-world problems as first-year students,” Turcatti said. “Thanks to EPICS, they don’t have to wait until they are seniors to work on (real-world projects) and start learning about the design process.”

EPICS at UTD is just two months from turning 10 years old. Now, the program regularly has 150 students enrolled, spread out over 30 projects. Turcatti has noticed students taking the course multiple times — even on a full academic schedule or after transferring to UTD — because the students love the experience.

“I think (students) choosing us (for their electives) tells us we’re offering something valuable to the students,” Turcatti said. “We have done what I consider to be a good job implementing EPICS. The consortium was a key element that helped us understand better and better what EPICS was and how to offer it.”

Arizona State University: Aiding the global community

Jared Schoepf had no idea what he was walking into that first semester in fall 2009.

As part of the inaugural EPICS course at Arizona State University (ASU) in Tempe, Schoepf didn’t have a precedent to compare, and worried that the course was going to take too much time.

Instead, EPICS became an integral experience for Schoepf that extended to all eight semesters of his ASU undergrad.

It ultimately inspired his future career path and ignited a passion for water quality, filtration and potable water access.

Schoepf’s first project in 2009 was to create a filter to remove harmful microbes and parasites from water for a community in South Africa. Designed to fit inside a 25-gallon water barrel — made to be pushed instead of carried, thereby reducing nerve and muscle damage — the filter served as a low-cost solution to a prevalent and life-altering problem.

The team made over 10 prototypes and delivered one system. Schoepf emerged from the experience with newfound confidence and plenty of ideas waiting to be explored.

Schoepf was hooked.

“EPICS is a great opportunity to conceptualize what a project’s reason is,” Schoepf said. “For me, there was a time where we were trying to calculate a force I couldn't figure out. I went to a previous professor who taught a course on it, which I had taken the previous semester, and he said, ‘Jared, that was literally a section in our class.’ I had been worried about earning points instead of learning the material and realized I needed to start paying more attention because these (courses) are applicable on real world projects. I hope that we bring that same kind of mentality to our students.”

The realization enriched Schoepf’s college experience, focusing his bachelor’s and master’s degrees into water quality and microbial work through EPICS projects, both as an undergrad student and as a graduate teaching assistant.

While pursuing his doctorate at ASU in 2013, EPICS received a new director. Schoepf decided it was the perfect time to see EPICS from a new angle: as an instructor. To the director, he pitched a project — his research of four years — as a great local problem for students to help solve.

But this one wasn't focused on the microscopic issues. This was a larger issue, physically: Schoepf proposed creating a new system to clear garbage from the streets after rainstorms.

“It doesn’t rain very often in Phoenix,” said Schoepf, an Arizona native. “Trash will slowly accumulate on the streets, and when it rains, the rainwater transports the trash all down the street drains. We have one main river where it all goes, and the trash collection system doesn’t work very well all the time.”

Schoepf’s love for EPICS — and continuous flow of ideas for his students to tackle — led to him accepting the role of co-director in summer 2017. Under his leadership, the program expands by about 100 students annually.

EPICS projects at ASU have also expanded in scope: Now, projects are available overseas as study abroad experiences. Currently, students can go to Indonesia, Kenya or Spain (and previously, to South Africa and Vietnam) to see the reasons behind their across-the-sea partnerships.

The most impactful project for Schoepf in recent memory is the Maymester to Kenya. An ASU EPICS team worked for several years with schools in Kenya to provide children long-lasting, high-quality reading materials. While donations vary between steady and sparse, the humid climate quickly eats away at print books, and online content is not a consistent option.

Older electronics often end up in smaller, rural communities and schools after being “recycled” from users in the United States.

“We created a digital library that doesn’t need internet to work,” said Schoepf, a proud smile as he recounted the project. “Most people in Kenya have phones, but they can’t afford internet. So the digital library works like a device in an airplane: You watch movies that are locally stored, not streamed. We can do the same thing with reading materials, books, videos and lessons.”

The solution was delivered at the same time as the study abroad. And it’s still working well, Schoepf has been told by partners in Kenya.

He hopes his students are as inspired by those projects as Schoepf is — maybe more so.

“EPICS hopefully sparks curiosity within our students like it did for me,” Schoepf said. “In all your classes and education, to some extent, you have to be curious enough to seek the knowledge, and EPICS creates this understanding that you have to ask questions and reach out and network for everything.”

EPICS consists of two distinct courses at ASU, giving students multiple avenues to learn and grow. EPICS I is lecture-based with a project to test budding design skills. EPICS II gives students free rein on a design project and direct contact with a community partner. Most years, each course has 20 sections with about 40 students each.

That’s 550 students across 80 projects and 20 industry mentors each semester.

“We've changed the curriculum quite significantly in the last five years,” Schoepf said. “The focus right now is going to industry people and asking, ‘What should we be teaching students to best prepare them for their career?’ The answers change what skills we make college-friendly versions of and integrate into EPICS.”

That’s the next goal for ASU’s EPICS staff: breaking into industry and gaining more connections, more partnerships and, ultimately, more projects.

Schoepf is excited to talk in-depth with EPICS at Purdue for ideas on finding, initiating and cultivating long-lasting industrial relationships. He wants students to approach the working world not only well equipped, but inspired and excited to create solutions to a multitude of problems.

Morgan State: Building reciprocal partners

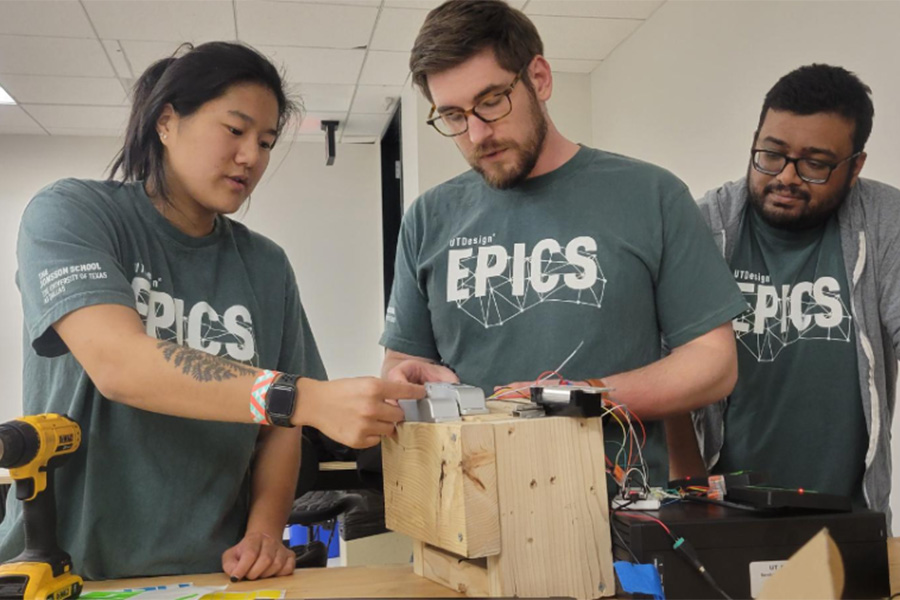

EPICS-modeled courses, which build foundational skills during engineering students’ senior design projects, are celebrating two years at Morgan State University (MSU).

The implementation has been a long time coming. For interim chair and associate professor for MSU’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering James Hunter (MSCE ’02, PhD CE ’06), memories of EPICS in talks at MSU span back to the university hosting the 2003 consortium workshop in Baltimore.

For Hunter, talks of EPICS in his own life started in 2000 when he was desperate for a cushion for his GPA.

“EPICS saved my academic career,” Hunter said. “I talked to Ron Lukash, a professor in civil engineering, because I was struggling with my courses. I was interested in constructed wetlands, and he said, ‘Oh, we have a constructive wetland team through EPICS.’ It got me caught up on what I needed to do academically, and it got me going with the EPICS program.”

Hunter continued work on constructive wetlands, both as an EPICS team member and as a dissertation for his civil engineering degree. He served as a TA for EPICS courses as a master’s student. After graduating with his master’s degree from Purdue, Hunter got to sit on the other side of the EPICS exchange: He was a member of the Tippecanoe County board while working with an EPICS team. He sat on the board to pick the new soccer club’s location in Lafayette, Indiana.

“Wearing those different hats helped me understand the impact of EPICS,” Hunter said. “Even seeing the facility change from (the levees) to the labs where students design, troubleshoot and test their projects really wowed me.”

When Hunter came on board as an MSU faculty member in summer 2018, it was a priority to get EPICS into motion. An academic partnership, returning as a design reviewer and bouncing ideas off MSU graduate and assistant director of high school programs Charese Williams only built the case for the positive impact of EPICS at Morgan State.

Morgan State senior design students worked with a Purdue EPICS team to create a community center in Baltimore. The Purdue team provided ideas from a previous community center project from Lafayette, and the Morgan State team adjusted the ideas to fit the climate, the flood patterns, the urban spread and the community needs within a church that had volunteered its space.

It was an inspiring project, Hunter said. Morgan State students regularly express interest in studying at Purdue and working with EPICS teams, especially after that project’s collaboration.

“There's something very special about the EPICS program,” Hunter said. “Most engineering students aren't really going out into the community and talking to people. This forces our students, whether it's at Purdue or Morgan, to interact with their stakeholders, particularly for our students and civil engineering. A lot of them end up working for the city, county or the state, so communicating and being prepared for feedback, good and bad, is crucial.”

EPICS curriculum was implemented into senior design courses at MSU in 2023. Now, the university is working to expand the program to first-year students and sophomores to start teaching them early on what makes a good, impactful and fulfilling community engineering project.

“This has come full circle, being now back at my alma mater, at Morgan State University and then being able to help bring EPICS to Morgan… it’s been the coolest thing to watch unfold,” Hunter said. “Students are seeing these senior capstone design projects and seeing that there’s a pathway to impacting the community and becoming a great engineer. We want to do that at Morgan State. We see innovation that can come out of EPICS.”

Morgan State is situated in Baltimore and regularly deals with strong storms and flooding from the Chesapeake Watershed. That, combined with infrastructure that dates to the genesis of the United States, makes for unique environmental, infrastructural and community projects ripe for EPICS students to take on.

For Hunter, a civil engineer, helping his city address its challenges is a continual source of inspiration.

“Everything just sort of converges with the different partners and the individuals on the product side,” Hunter said. “Right now, EPICS is the framework that we use for our senior project. We want to use it for our first-year students so they’re able to think about and work on these projects for years.

“Morgan State is also growing into the neighborhoods, and there's an opportunity to connect the university, its students and the community to each other in order to solve these common issues in infrastructure. It’s a great ground for students to become community-minded engineers and be exactly what industry needs.”

The EPICS model is available to hundreds of universities, high schools and middle schools through generous gifts and consequential leaders. Contributions to EPICS K-12 provide training and free curriculum resources to EPICS K-12 students and teachers. Become an EPICS partner by giving a gift.