When a self-piloted vehicle is making decisions, any delays in the process could make the difference between life and death. The biggest delay in that decision-making is often in the camera hardware says Takashi Tanaka, AAE associate professor.

To understand the world around it, the human eye and brain process the world continuously but identifying changes over time. That’s part of what makes humans incredibly adept at making split-second decisions, with a reaction time around 200 milliseconds. We’re not processing every single thing in our field of view all the time — we’re mostly noticing what’s new in any given moment, Tanaka says.

Cameras, however, view the world as a series of complete pictures. A traditional camera might capture a frame every 30 milliseconds, but autonomous vehicles have compounding steps between image capture and action.

They need to transfer the frames to memory, identify objects in each frame, process and analyze each object in context with adjacent frames, and identify any relevant changes before it can come to a decision. There’s simply a lot of data throughput and processing power required. Robotic reaction time slows further when those images are transmitted wirelessly to an off-device computer.

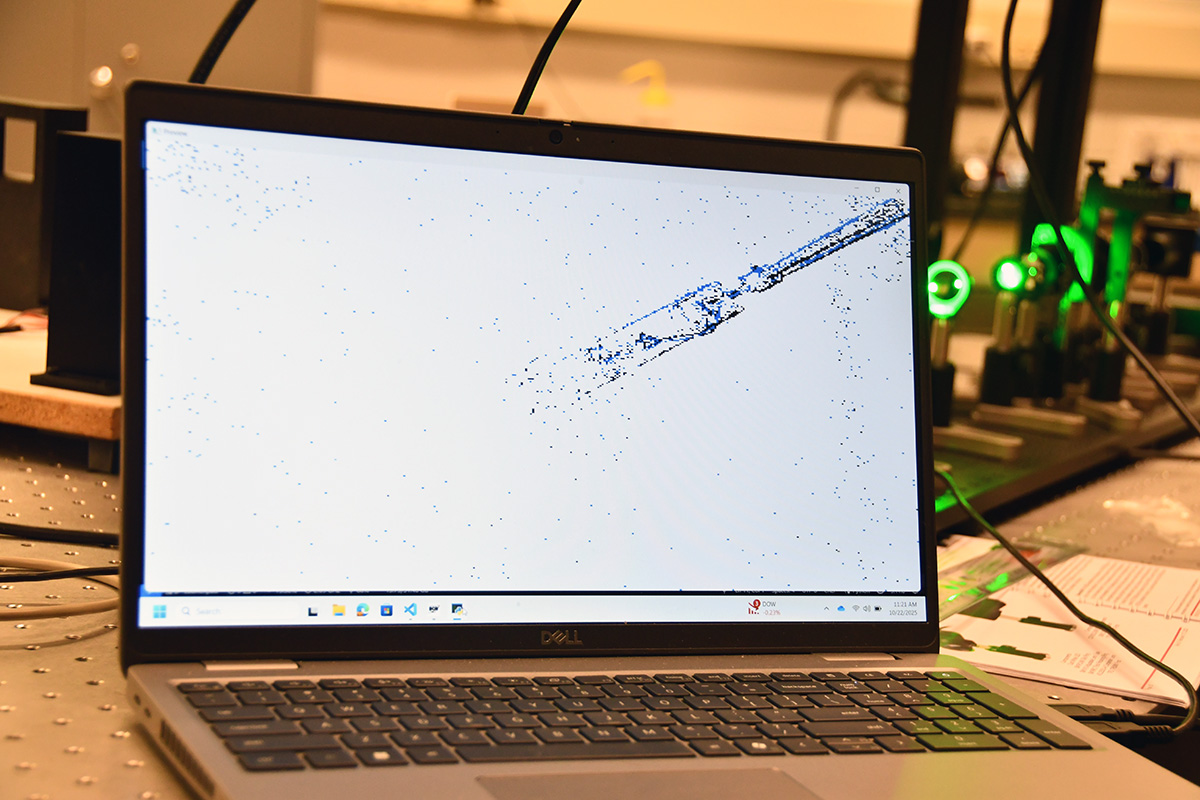

This output from Prof. Tanaka's event camera shows the areas of the camera's sensor that detect change from the previous moment.

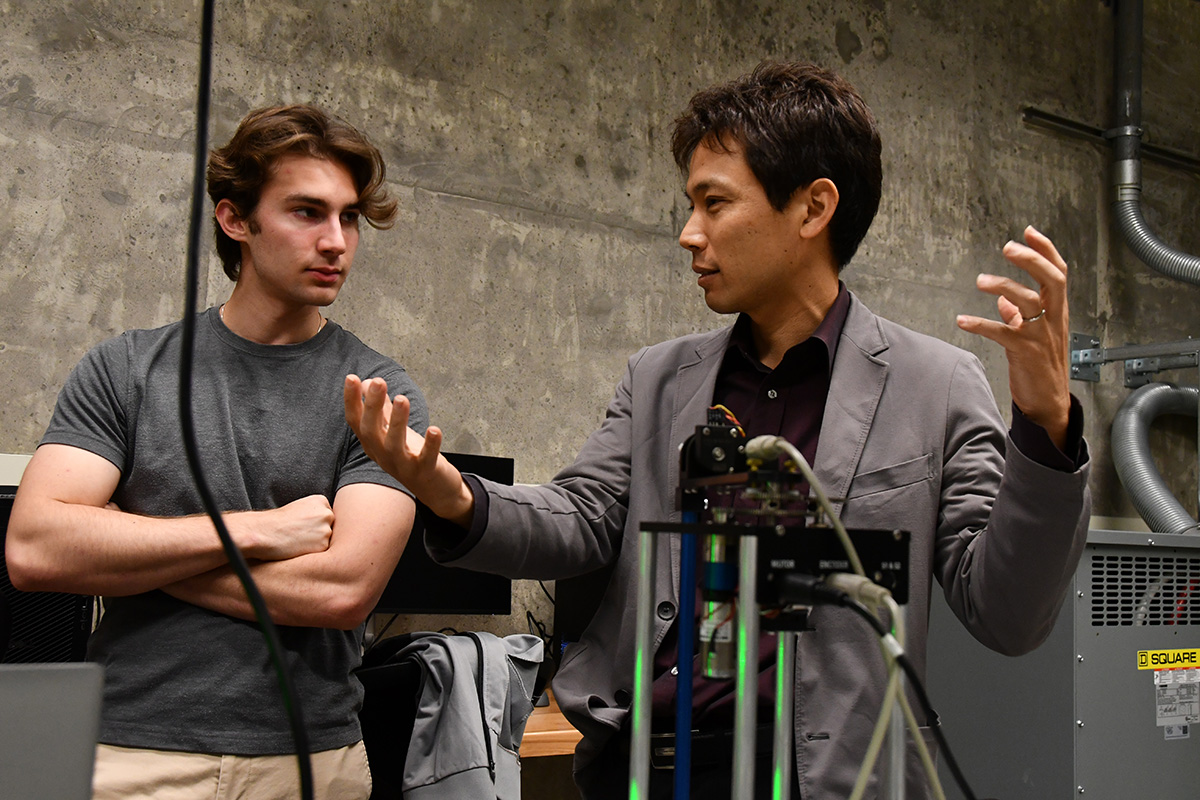

That’s why Tanaka is pursuing control system designs that are inspired by living creatures. His work in neumorphic perception is exploring the use of “event cameras,” a technology that takes a more human approach to vision. Instead of capturing complete, consecutive frames of image data, an event camera detects changes frame to frame — making it capable of giving instant-reaction information, while also reducing the data transfer and processing challenges of traditional cameras.

Event cameras operate at a frequency around 30,000 frames per second — many orders of magnitude faster than a traditional camera. This is possible because, “it is sensitive only to the moving portion of any pixel,” Tanaka says. “It gives an X and Y position, a polarity, and a time value of moving objects. For collision avoidance, fast processing and feedback control are critical. We are designing control systems for things like collision avoidance based on these unique vision systems.”

As an undergraduate student at the University of Tokyo, Tanaka was involved in building the first successful CubeSat: The XI-IV, which launched in 2003 and remains in stable orbit 820 km above Earth. His soldering and other hands-on work were carried to space on three different CubeSats that are still operational today.

But he didn’t fall in love with autonomy and control until he was in the U.S., doing control theory research while pursuing an advanced degree at University of Illinois. Today, he studies the ways machines can take a sensor input and use it to adjust its behavior.

Many machines operate exactly the same way, continuously, over and over — like a robot in an assembly line, making the same weld or attaching the same component to a thousand cars a day. But when a machine continuously monitors its sensors to tweak how it’s performing that task, that’s called a feedback loop. It’s similar to how a human might see a pothole and adjust their car’s position in a lane or hear a siren and look for an ambulance to determine if they need to pull over.

“Feedback is a type of magic that can turn a crude mechanism into a very finetuned system,” Tanaka says.

Throughout his research, from his post-doctoral work at MIT and KTH Royal Institute of Technology to his time as an assistant professor at UT Austin, he delved into the man-made science of control systems. He continues to use humans and other living creatures as inspiration for how to break new ground in machine behavior.