Everyone at Purdue knows the legend: if you walk under the Bell Tower, you won’t graduate in four years. One day, a team of undergraduates wondered, “What would happen if you could hop over it?”

PSP Active Controls is a team of 80 students dedicated to vertical takeoff and vertical landing (VTVL) technology, aiming to build a fully reusable lander vehicle to compete in the Collegiate Propulsive Lander Challenge. We’re part of Purdue Space Program, a chapter of Students for the Exploration and Development of Space – and one of the biggest student clubs on campus.

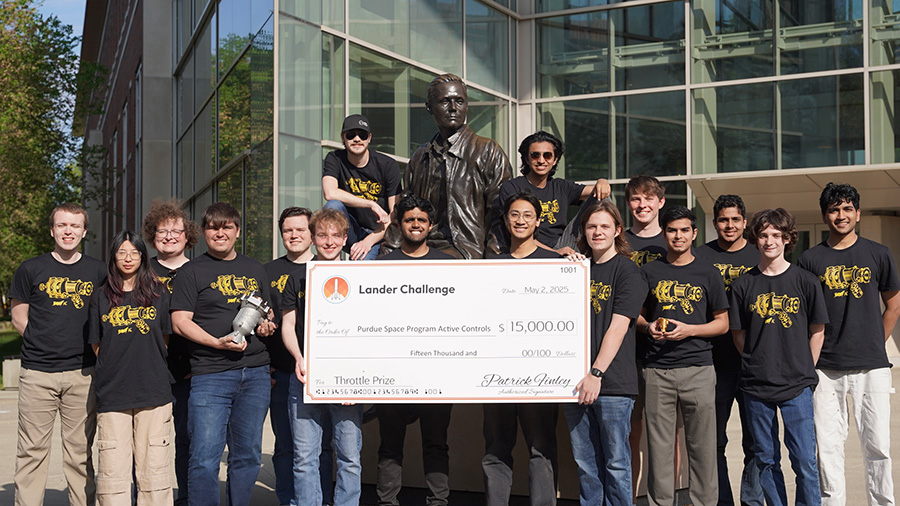

In Spring 2025, PSP Active Controls demonstrated throttling capability in our liquid rocket engine and won $15,000 for the Throttle Milestone.

It was loud, messy, and exhausting. It was also the most rewarding engineering experience any of us has had.

The Lander Challenge pushes students into the frontier of amateur liquid-fueled rocketry, with the final goal being a powered 160 foot hop, coincidentally the exact height of the Bell Tower. Teams progress through five milestones, from test stand hotfires to a vehicle that can land itself. Competing globally adds pressure. If we want to be the team that performs the hop, we need an engine that throttles reliably.

Enter TADPOLE.

TADPOLE was our first regeneratively cooled bipropellant liquid rocket engine, designed to meet industry-level expectations for reusability. In 2024, we partnered with Elementum 3D to use their proprietary Al6061-RAM2 alloy, previously tested by NASA. Suddenly, professionals were watching to see if undergraduates could deliver on an ambitious technical promise.

For almost a year, we waited for a spot on the 10k Stand at the Maurice J. Zucrow Laboratories. When we finally secured it for a month in April 2025, we arrived the next day ready to fabricate, assemble, and test for as many hours as the facility allowed.

Every campaign starts with baby steps: verify the torch ignites, run a three second “burp” for stable ignition, then a ten second steady state burn, and finally a full 20-second hotfire to confirm the chamber can survive the throttle duration. Those “simple” tests revealed how little margin exists in real engines. Any leak, loose wire, or loss of control can halt progress.

Andrew Radulovich stands beneath the cryogenic propellant lines to inspect throttle valves after coldflows

Throttle tests brought forth the engine’s true capability. A lander vehicle must go up, hover, and come down gently, requiring mastery of the steady state and transient engine behavior. Firing with integrated throttle valves was the heart of the challenge, where we proved engine controllability.

We learned fast. In a one-month campaign, minutes matter. Each subsequent test depends on interpreting sensor data, identifying anomalies, and adapting quickly. We learned to trust our instrumentation, trust each other, and trust the preparation behind each test.

Our favorite part wasn’t just the Mach diamonds, it was the repetition. We tested so frequently that some of us lost interest.

This was intentional. Reusability shouldn’t feel cinematic; by the tenth test, it should feel routine. When firing a liquid engine becomes second nature, that’s when real progress begins.

Meanwhile, other teams raced toward the same milestone. We secured the final throttle prize by just one day. The results speak for themselves: TADPOLE became Purdue’s first throttleable liquid rocket engine and first regeneratively cooled hotfire at the undergraduate level. We accumulated more than 160 seconds of burn time, including multiple continuous twenty-second hotfires.

Active Controls presents the $15,000 prize awarded by the Lander Challenge in front of Armstrong Hall, celebrates senior class graduation

Winning the milestone prize validated our work, but the bigger impact was realizing that undergraduates can achieve complex goals. This campaign unified years of mechanical, electrical, aerospace, and computer science work. TADPOLE now guides the design for its successor, superTADPOLE, with all design, control, and cooling strategies informed by real test data.

This effort is possible because of Purdue. Few universities give undergraduates direct access to propulsion facilities like Zucrow Labs or fabrication spaces like the Bechtel Innovation Design Center. Even fewer encourage pushing student teams to the limits. At Purdue, propulsion isn’t reserved for graduate school. It’s something you can do your freshman year, on a Tuesday afternoon, supported by mentors who treat student hardware professionally.

Liquid propulsion is no longer something students admire online. It is something that we build, test, analyze, and iterate on ourselves. As the aerospace industry accelerates, students will increasingly be part of that growth, not spectators of it.

So look out. Someday, sooner than people expect, we plan to hop over that Bell Tower.