December 13, 2018

Data use draining your battery? Tiny device to speed up memory while also saving power

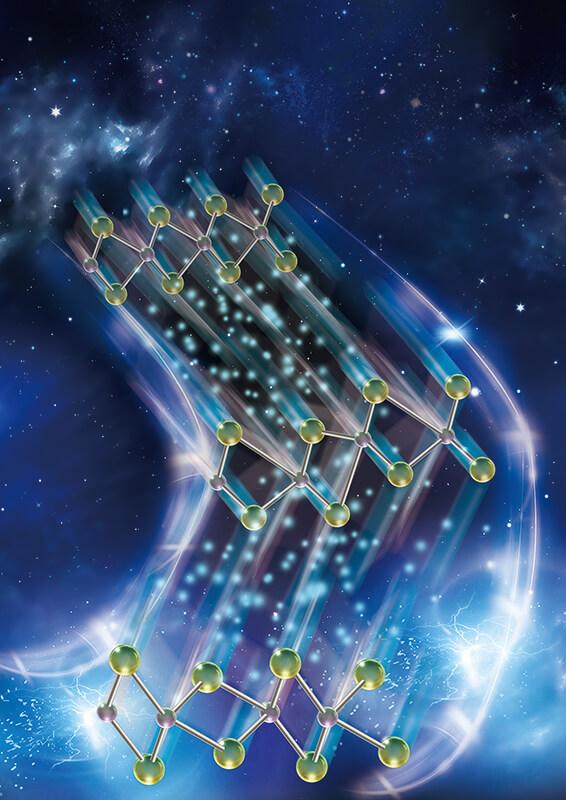

Researchers have discovered a new functionality in a two-dimensional material that allows data to be stored and retrieved much faster on a computer chip, saving battery life. (Purdue University illustration)

Download image

Researchers have discovered a new functionality in a two-dimensional material that allows data to be stored and retrieved much faster on a computer chip, saving battery life. (Purdue University illustration)

Download image

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — The more objects we make "smart," from watches to entire buildings, the greater the need for these devices to store and retrieve massive amounts of data quickly without consuming too much power.

Millions of new memory cells could be part of a computer chip and provide that speed and energy savings, thanks to the discovery of a previously unobserved functionality in a material called molybdenum ditelluride.

The two-dimensional material stacks into multiple layers to build a memory cell. Researchers at Purdue University engineered this device in collaboration with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and Theiss Research Inc. Their work appears in an advance online issue of Nature Materials.

Chip-maker companies have long called for better memory technologies to enable a growing network of smart devices. One of these next-generation possibilities is resistive random access memory, or RRAM for short.

In RRAM, an electrical current is typically driven through a memory cell made up of stacked materials, creating a change in resistance that records data as 0s and 1s in memory. The sequence of 0s and 1s among memory cells identifies pieces of information that a computer reads to perform a function and then store into memory again.

A material would need to be robust enough for storing and retrieving data at least trillions of times, but materials currently used have been too unreliable. So RRAM hasn’t been available yet for widescale use on computer chips.

Molybdenum ditelluride could potentially last through all those cycles.

“We haven’t yet explored system fatigue using this new material, but our hope is that it is both faster and more reliable than other approaches due to the unique switching mechanism we've observed,” Joerg Appenzeller, Purdue University's Barry M. and Patricia L. Epstein Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering and the scientific director of nanoelectronics at the Birck Nanotechnology Center.

Molybdenum ditelluride allows a system to switch more quickly between 0 and 1, potentially increasing the rate of storing and retrieving information. This is because when an electric field is applied to the cell, atoms are displaced by a tiny distance, resulting in a state of high resistance, noted as 0, or a state of low resistance, noted as 1, which can occur much faster than switching in conventional RRAM devices.

"Because less power is needed for these resistive states to change, a battery could last longer," Appenzeller said.

In a computer chip, each memory cell would be located at the intersection of wires, forming a memory array called cross-point RRAM.

Appenzeller's lab wants to explore building a stacked memory cell that also incorporates the other main components of a computer chip: "logic," which processes data, and "interconnects," wires that transfer electrical signals, by utilizing a library of novel electronic materials fabricated at NIST.

"Logic and interconnects drain battery too, so the advantage of an entirely two-dimensional architecture is more functionality within a small space and better communication between memory and logic," Appenzeller said.

Two U.S. patent applications have been filed for this technology through the Purdue Office of Technology Commercialization.

The work received financial support from the Semiconductor Research Corporation through the NEW LIMITS Center (led by Purdue University), NIST, the U.S. Department of Commerce and the Material Genome Initiative.

Writer: Kayla Wiles, 765-494-2432, wiles5@purdue.edu

Source: Joerg Appenzeller, 765-494-1076, appenzeller@purdue.edu

Note to Journalists: For a full-text copy of the paper, please contact Kayla Wiles, Purdue News Service, at wiles5@purdue.edu.

ABSTRACT

Electric field induced structural transition in vertical MoTe2 and Mo1-xWxTe2 based resistive memories

Feng Zhang1, Huairuo Zhang2,3, Sergiy Krylyuk2,3, Cory A. Milligan1, Yuqi Zhu1, Dmitry Y. Zemlyanov1, Leonid A. Bendersky3, Benjamin P. Burton3, Albert V. Davydov2 and Joerg Appenzeller1

1Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA

2Theiss Research Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA

3National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA

doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0234-y

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have attracted attention as potential building blocks for various electronic applications due to their atomically thin nature and polymorphism. Here, we report an electric field induced structural transition from a 2H semiconducting to a distorted transient structure (2Hd) and orthorhombic Td conducting phase in vertical 2H-MoTe2 and Mo1-xWxTe2 based resistive random access memory (RRAM) devices. RRAM programming voltages are tunable by the TMD thickness and show a distinctive trend of requiring lower electric fields for Mo1-xWxTe2 alloys vs. MoTe2 compounds. Devices showed reproducible resistive switching within 10 ns between a high-resistant state (HRS) and low-resistant state (LRS). Moreover, using an Al2O3/MoTe2 stack, On/Off-current ratios of 106 with programming currents lower than 1 mA were achieved in a selectorless RRAM architecture. The sum of these findings demonstrates that controlled electrical state switching in two-dimensional materials is achievable and highlights the potential of TMDs for memory applications.